Seattle’s alternative “grunge” rock was a punk/metal hybrid sound made famous by bands like Pearl Jam, Nirvana, and Soundgarden that seized pop culture in the early ’90s. Among the musicians who came to define the scene, white men dominated, and women were few. And Black women? If the most common version of history is to be believed, there were none. But that version is wrong.

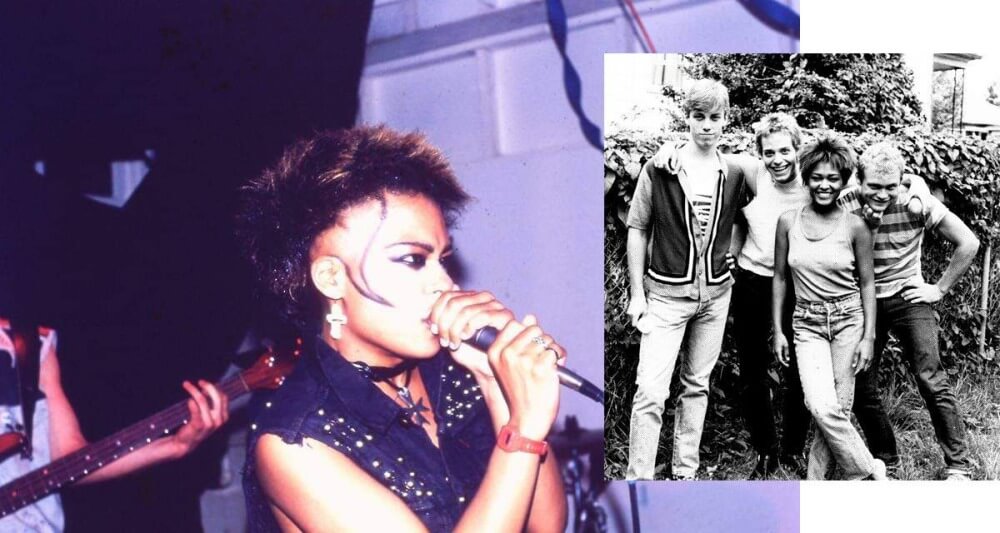

Bam Bam, formed in 1983 by husband-and-wife duo Tommy Martin and Tina Bell, has largely been erased from the annals of the genre. But they were, in fact, one of the very first Seattle bands to experiment with merging the down-tuned guitars of metal and the fury of punk to create what would soon be known as “grunge.” And Bam Bam was defined by Bell—a young Black woman fronting a post-punk band in the early ’80s.

By all accounts, the late Tina Bell had star power. At five-foot-two, she was a powerhouse of vocal ability, fierce energy, and stunning beauty who left a mark on the crowds she played for. Yet until recently, she’s rarely been mentioned in the chronicles of grunge. Even Everybody Loves Our Town, Mark Yarm’s acclaimed oral history of the genre—widely considered to be the definitive one—describes Bam Bam without mentioning Bell.

Twice-voted Best Seattle Band by listeners of local radio stations KEXP and KCMU, Bam Bam notably played alongside famous contemporaries like Alice in Chains and Pearl Jam. On the Melvins’ first U.S. tour (with Kurt Cobain as their roadie), they were the opening act for Bam Bam. Bell and Martin had songs that rivaled the early work of their peers, such as “Ground Zero” and “Free Fall from Space,” yet somehow, they were never signed. Some blame missteps in the band’s choices, others point to Seattle’s historic erasure of Black artists—even Jimi Hendrix had to leave his hometown to get noticed—or just rock ‘n’ roll’s whitewashing in general. But a recent reissue of the band’s EP Villains (Also Wear White) from Bric-a-Brac Records and tireless efforts from the band’s original bassist, Scotty Ledgerwood, have renewed interest in the group and the ways in which Bell inspired not only the scene she helped to shape, but also a whole generation of artists.

Born in 1957 in Seattle, Bell was one of 10 children. She got her start singing at Mount Zion Baptist Church in Seattle’s Central District, the center of the city’s Black community throughout the 1970s. As a teenager, she appeared on stage in a performance with the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute for which she sang Henri Betti’s 1947 song “C’est Si Bon” in French. In search of a language tutor while preparing for the show, she met Tommy Martin, who had been an exchange student in France when he was a kid. The two became romantic partners and Bell gave birth to a son, T.J., in 1979. Shortly after, the couple married. They lived together in a tiny basement studio in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. Martin drove a bus part time and Bell worked at a check-cashing service.

In the spring of 1983, Martin placed an ad in The Rocket, a free biweekly music ’zine in Seattle. “Forming punk band, need bass and drums,” the ad read, as Ledgerwood recalls, and he responded to it. “Tommy was intimidating, but meeting Tina was an overwhelming—dare I say—religious experience. She was so stunningly beautiful; rudely beautiful, I used to always say. But she didn’t ask me a thing about music. She wanted to know about my family, my wife, my mom, and my son. What my life was like, who I was. Within an hour we were pals.”

With guitar, bass, and vocals sorted, the trio got to work. “We went headlong into a hard-core, full-time job sort of rehearsing—six days a week, seven hours a day,” Ledgerwood says. “Our priority was making music. Tina and I would lie on the floor while Tommy played guitar and tossed papers at us. We’d write songs that way.”

Matt Cameron, Grammy-winning drummer from the bands Soundgarden and Pearl Jam, would join the group later that summer, shortly after moving to town from San Diego. “I answered an ad in The Rocket,” he remembers. “Then I went to Tina and Tommy’s place, where they lived and rehearsed. Scotty was there, too. I guess I looked like a lost babe in the woods at that time because I remember Tina welcoming me with open arms. A big smile and a big hug. Everything about her was like, Wow, this lady has it. I hadn’t heard a lick yet, but I could tell she had that star power. We just dove right in and started jamming together.”

Dubbed Bam Bam, short for “Bell and Martin” twice, the band would play their first show that fall at The Metropolis, a short-lived, all-ages venue where touring bands like the Gun Club, Bad Brains, and Hüsker Dü would play. “The band was really tight, and the music rocked,” Cameron remembers. “It was loud, fast, and aggressive. Fiery guitar, fiery singing, amazing lyrics. The kind of sound I wanted to dig into at the time.”

“Tina was literally the only Black woman on the scene then,” says Ledgerwood. “The suits and ties couldn’t see our relevance, but the crowds usually ate us up, especially her. Tommy was leader of the band until we got on stage. Then it was ‘the Bell.’ Without question, she set the pace. If the crowd was slightly less than enthusiastic, she would get fiercer. We followed suit. She was so dynamic, so unpredictable, and so energetic. I’ve never seen a more explosive performer.”

“She was so fucking badass,” concurs Bell’s friend Christina King, a photographer who often attended the band’s rehearsals. “I didn’t really like a lot of women in music at that time, but she was so sweet and so beautiful. There was a fire in her and a little bit of anger. Put it all together, and she was the ultimate package—what I thought a woman should be.”

“On stage she was so powerful and fearless in everything she did,” recalls friend and Brides of Frankenstein frontwoman Faye Mills. “I used to wonder how someone so tiny had so much force.”

The following year, Bam Bam would be producer Chris Hanzsek’s very first client at his newly opened studio, Reciprocal Recording, where bands including Mudhoney, Screaming Trees, and Nirvana would lay down tracks for some of their earliest work. Over several sessions, Hanzsek captured Bam Bam’s Villains EP and single “Ground Zero.” Martin’s signature down-tuning and sludgy rhythms decelerated punk riffs into a heavy hybrid of rock and metal. Together with Bell’s angst-filled lyrics, these are likely the earliest examples of the now-familiar “grunge” sound. Hanzsek told Billboard in 2011 that the first band he worked with after those sessions with Bam Bam was Green River, largely considered to be the progenitors of the movement, even though they didn’t release their first album until 1985—a full year later.

According to many familiar with Bam Bam, this omission of the band from the history of grunge could have everything to do with racism and misogyny. “A lot of people didn’t get Bam Bam,” says King. “I remember someone seeing one of their fliers at my house and saying, ‘I just don’t get the female Black singer thing,’ which didn’t make sense to me. I had seen Black people in punk rock and there were women in punk rock. I don’t remember anybody ever saying that about Bad Brains.”

Similarly, Ledgerwood recalls the band encountering racial harassment both on stage and off. “One of our most ferocious shows was after two guys yelled [racial slurs] at Tina while she was on stage at The Metropolis,” he says. “She took the mic stand and bashed one guy’s head in. Tommy dove into the crowd with her. [Racist attacks] didn’t happen often, but they hurt just the same. I was also with her when some asshole on the street called her [a racial slur] and threw a McDonald’s cup at her, which hit me right in the face. Those were my brief glimpses into the racism she had to endure every day.”

Seattle-based Afro-punk musician and feminist activist Om Johari became a fan of Bell after seeing Bam Bam performing in the 1980s. “In my late teen years, Tina Bell was the person I saw myself most in,” Johari says. “Her eyes, her demeanor, her words, and the ways she expressed herself exemplified what it was like for many of us ‘Black weirdos’—too weird to be Black, but too Black to be weird in the white community—to exist in these predominantly white spaces, but also to have our own cultural interests shaped by the opinions of the white gaze. I think wading through the Northwest weighed heavily on Tina.”

Bell and Martin’s son, T.J. Martin—now an Oscar and Emmy award-winning filmmaker—also recalls race and gender being major determining factors in his parents’ creative journey. In 1986, the couple dropped their seven-year-old son off at boarding school in a small town south of Léon, France, before trying to make it in London and Amsterdam for two years. “They felt audiences there would be more open to a Black female lead singer,” T.J. explains. “They thought there’d be more resonance, specifically in the U.K., not just with their sound but also with how they looked and who they were. They wanted to put themselves in a position to really focus on making music and see if they could get signed.”

The couple’s move to Europe was a decision that turned out to be an unfortunate mistake, and it changed their futures in numerous ways. For one thing, it resulted in the dissolution of their marriage. “They tried to keep it under wraps, but it was very evident,” T.J. recalls of that time. “They would come to visit me in France, or I would go to see them in London. Initially, there was a concerted effort to go on outings as a family. But they would fight aggressively, which wasn’t necessarily anything new—it was the same in Seattle—and they seemed more flippant with each other. Where previously, they were intensely trying to keep the family unit together, now they could storm out and go elsewhere. Then, at a certain point, I’d just see them separately. They were living apart and I think they were both dating other people.”

Nevertheless, though the pair had split, they continued to play music together upon their return to Seattle. But it was too late. “The irony is that the ‘evolution of grunge’ happened at the same time [they were in Europe],” says T.J. “It was when Sub Pop started to blow up, people were starting to pay attention to what was happening in Seattle, and they’d left. By the time they came back, a lot of the bands they’d been playing with were either signed or being considered by major labels or had something happen in their careers over those two years while they were away. All these other bands were also starting to move to Seattle from other places to get recognized. It was this critical window that they missed. My dad held onto that until he passed [in 2019 of a heart attack]—this chip on his shoulder from never being seen or recognized for who they were or their contributions to the scene.”

“They were both pretty unstable at that point,” T.J. says of his family’s return to the U.S. “I’d stay with grandparents, aunts, uncles. After Europe, my mom started getting disillusioned with the industry and the band, in addition to their marriage. They still played together, but there were fewer and fewer shows. Partly because I think my mom was losing her connection to the world.”

photos by Christina King

photos by Christina King

“Off stage, she was this fun-loving best friend who loved to tell stories, draw, write, and make art,” says Mills. “But I watched her struggle with depression then, too. She’d pull back a lot and you wouldn’t see her for a while. She’d just disappear.”

Ledgerwood, who left the band before Martin and Bell went to Europe, points to the overbearing atmosphere perpetuated by Martin as the reason both for his departure, and eventually, for Bell’s. Bell quit music entirely and moved to Las Vegas in 1990. “It was Tommy’s band,” says Ledgerwood of Bam Bam. “He was in charge, but sometimes he was a little too pushy. It was frustrating and because of that, I left. It was too much for me. It wore us all down. Tina left because Tommy started getting so eclectic and so crazy, writing stuff that sounded like Frank Zappa’s Jazz from Hell or like Mr. Bungle. It was just this insane stuff that no one could sing over. It didn’t work. Tommy was an extraordinarily brilliant man but sometimes had an overbearing personality. He cut ties with Chris from Reciprocal Recording rather abruptly. I don’t know what happened, but he didn’t like Chris and that’s why they didn’t sign us at a time when nearly every other band on the scene got signed.”

For the most part, Bell never spoke about the band again. “She felt betrayed by the world and buggered off to Vegas,” Ledgerwood explains. “Not just to get away from music but also to get away from her family and friends and everything else.”

T.J. agrees. “She just started sheltering herself from everything and everyone,” he says. “She did this interesting 180—from being a very vulnerable, fierce frontperson to slowly retreating and sitting in an apartment, hiding herself from the world, just kind of stewing in her emotions and thoughts. She was writing but not sharing any of it. She did not talk about her relationship to music in the past. She totally retreated and became a hermit. She struggled with alcoholism her whole life. It was very infrequent that I saw her or spoke with her, but it turns out that no one really did.”

Ledgerwood describes Bell listening to music constantly—from Frank Sinatra to the Doors to the Dead Kennedys—and catching up on the phone with family. T.J. recalls her becoming increasingly interested in spirituality, astrology, and reading the Bible as a way, he speculates, to understand the earliest parts of her life and connect with her own mother. But little remains of Bell’s life in Las Vegas. She passed away in October 2012 of cirrhosis of the liver. She was only 55 years old. When her body was found, the coroner estimated that she’d passed nearly two weeks earlier. Within 48 hours of being notified, T.J. drove from L.A. to Las Vegas to collect her belongings. But there was virtually nothing left. “When I arrived, they had disposed of all of her things except for a shitty wooden chair, a laminated poster of a bunch of family photos, and a DVD player. Maybe one other totally random item, but that was it,” he says. “They said they had to throw everything else away because it was ‘contaminated.’ But no one had mentioned anything like that before I made the trip.”

“She lived a very modest life,” T.J. continues. “She was on Social Security; she didn’t have a job or many belongings. The things she had that were of importance would have been her demo tapes, her books, and her writing. Without any concern, those things were thrown away. I couldn’t understand how they didn’t fathom how unbelievably offensive that was. If this had been a multimillion-dollar condo unit or apartment in Miami or some shit like that, no one would’ve touched any of those items without consulting her family, no matter what the state of the place was. It’s crazy.”

“Prior to about 2020, she was just invisible,” T.J. says of his mother. “She was invisible as a frontperson, and she was invisible even in death. The carelessness with which she was treated by the outside world is devastating. She lived an inherently unique life in an inherently unique set of circumstances. And as a result, she was a pioneer in her own regard. Even though [my parents] were young, there was a tremendous amount of thought and hard work put into their music. If you had the privilege of experiencing her on stage, you’re not getting someone putting on an act. You’re getting Tina Bell, presenting herself, in probably one of the truer forms of who she was, embodying the fierceness, embodying the fun, but also finding some solace on stage. There was a real authenticity to what was coming out of her, both in writing and performing.”

As T.J. considers ways to honor his mother’s legacy with his own work as a filmmaker, her memory also lives on in the people whose lives she touched. “[When we met], I was trying to find myself as a young musician and drummer,” Cameron says. “I would try some weird stuff I was learning on those guys—jazz beats and shit—and Tina would say, ‘Do more of that.’ She encouraged me to experiment.”

“Tina inspired a lot of people to be better, especially women,” recalls Mills. “She was always pushing us to show our power and be our best on stage. She led the way for other women in Seattle. She was one of the most powerful forces we had here.”

“She was, like, the ultimate big sister for me,” King recalls. “I had a lot of problems at home and she looked out for me. She and Tommy both became like my extended family.”

“I treasured our friendship. She really encouraged me and gave me the confidence to go on and form my own band,” Ledgerwood says. “I’m forever indebted to her for the way she helped me believe in myself. The confidence she had in me made me feel that I owed it to her to give more than my best. Tina Bell brought out the best in me.”

by Andrea Bussell

left header photo by Christina King, right by John ‘Hempfest Santa’ Seth (1983); 2nd block of photos by Christina King

This article originally appeared in BUST’s Summer 2022 print edition. Subscribe today!