In the new book, Comrade Sisters, author Ericka Huggins recalls the women she served alongside as a member of the Black Panther Party in the ’60s and ’70s. In this excerpt, accompanied by riveting historical images shot by photographer Stephen Shames and quotes from women who were part of the moment, she captures the drive, optimism, and vision of a generation of activists that decided, “if the government wouldn’t take care of its people, we would do it ourselves”

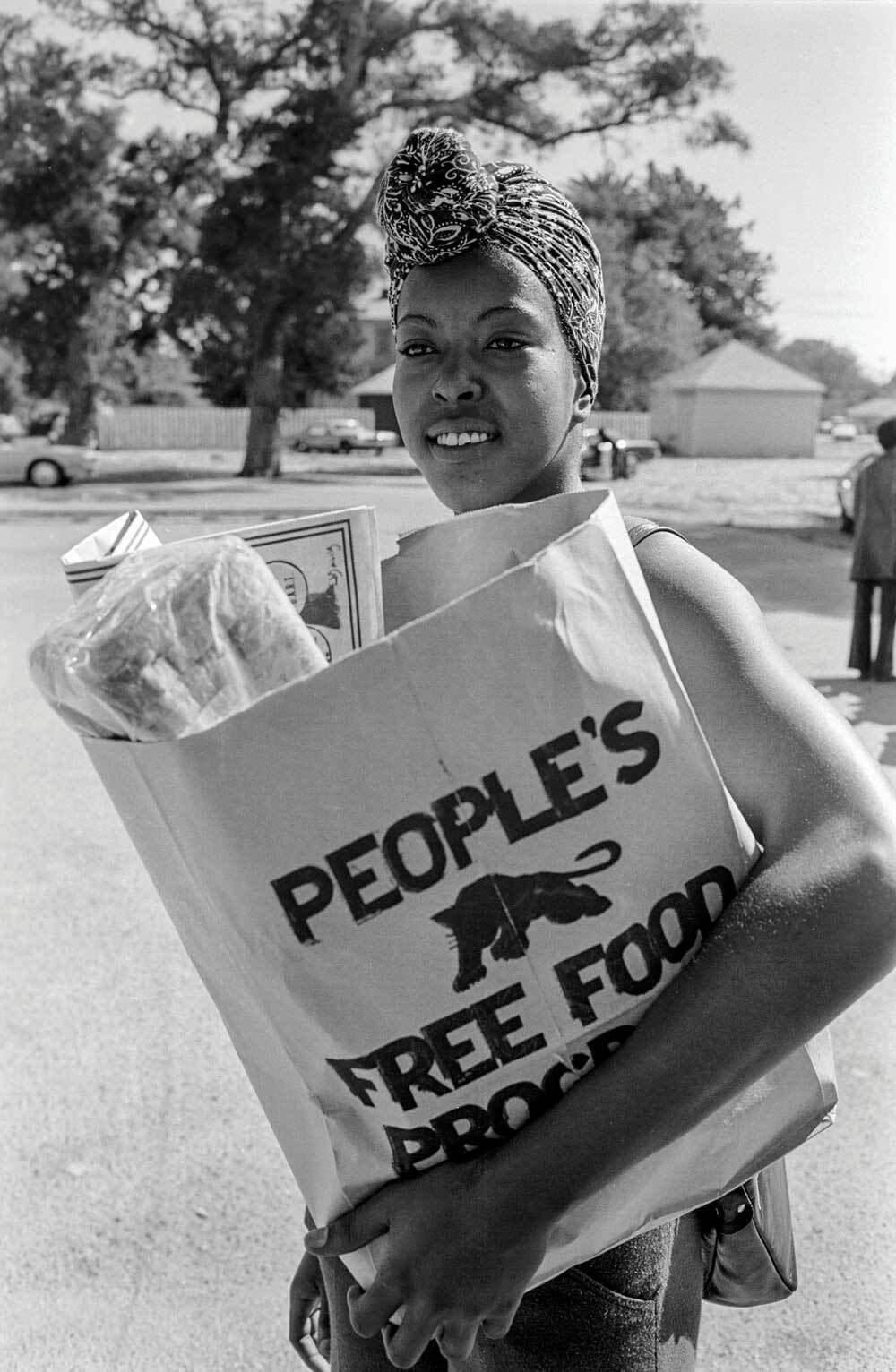

Palo Alto, CA, 1972: Woman with a bag of food at the People’s Free Food Program, one of the Survival Programs

Palo Alto, CA, 1972: Woman with a bag of food at the People’s Free Food Program, one of the Survival Programs

IN LATE 1966, two young men, Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, then students at Merritt College in Oakland, CA, discussed their concerns about the historic dismissal of the human rights of Black and oppressed people in the United States. Outraged by so many routine deaths caused by systems that furthered conditions of poverty for millions—limited healthcare, inadequate housing, food insecurity, police abuse, and over-incarceration—they agreed to form an organization to defend and redefine their communities. In October of that year, Seale and Newton conceived the Black Panther Party (BPP) for Self Defense—a group that would soon become a force for the social, political, economic, and spiritual uplift of Black and Indigenous people of color coast to coast.

Beginning with community police patrols and Free Breakfast for School Children programs, the BPP expanded out of Oakland to open offices in over 40 states in the U.S. Sixty Community Survival Programs sprung up in big cities and rural towns across the country. Their goal was to meet basic human needs—to provide land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace (namely by opposing the Vietnam War).

We were young and we were united in the belief that if the government wouldn’t take care of its people, we would do it ourselves.

By 1969, women accounted for more than half of all Black Panther membership. Women from every state in the U.S.—and from across the world—were drawn to the possibility of a transformative movement for freedom. They were mothers, sisters, aunties, cooks, house cleaners, churchgoers, students, teachers, artists, factory and retail workers, poets, dancers, writers, and musicians—and I was among them. We were young and we were united in the belief that if the government wouldn’t take care of its people, we would do it ourselves. We would serve the people, body and soul.

The women of the Black Panther Party are not special in some way that separates them from others. They are simply women who decided that there had to be “a way out of no way” for Black and poor people. Given the opportunity to step forward and give, they spoke up and grew their innate skills to create brilliant models for community leadership.

They were motivated by love, and this love was demonstrated through their work in what became known as Community Survival Programs. The Free Breakfast for School Children Programs spread across the country, feeding children in recreation centers and church basements every morning before school for many years. Recognizing the needs of their community, women led the BPP to create People’s Free Medical Clinics, which offered family healthcare and sickle cell anemia testing. This led to the idea for a Free Ambulance Program. This initiative was created to make sure that people without money or proof of insurance received emergency transportation to the nearest hospital. Because in some cities, people were being left to die after having been refused ambulance service. At the Winston-Salem, NC, chapter of the BPP, volunteers were trained and licensed as Emergency Medical Technicians to staff the van of the Free Ambulance Program and provide this lifesaving service.

How did the party know what to offer? People spoke and we listened. We created free clinics, community food programs, activities for seniors and teens, a Bussing to Prison initiative so people could visit incarcerated family members, alternative “liberation” schools, after-school programs, and childcare centers. Every Community Survival Program was fully replicable in locations and cultures around the world.

We also created the Intercommunal Youth Institute, which was open to sons and daughters of members of the BPP and a few families from the neighborhood. When the community pleaded with us to open the school to all families with children, we listened, and created a model elementary school, The Oakland Community School (OCS). It opened its doors in the 1973-74 school year and remained open until 1982. It was community based, tuition free, child centered, and parent friendly. We served three meals a day and took care of every child’s health needs through an arrangement with the Oakland Children’s Hospital. The OCS motto was “the world is a child’s classroom,” and we were dedicated to helping children learn how, not what, to think.

We owe a shout of gratitude to these women who have been unknown and unsung for so many years. As you reflect on the beauty and the messages in each of these photographs, and personal recollections, I encourage you to hold in your hearts the experiences of each of these women, told in their own words.

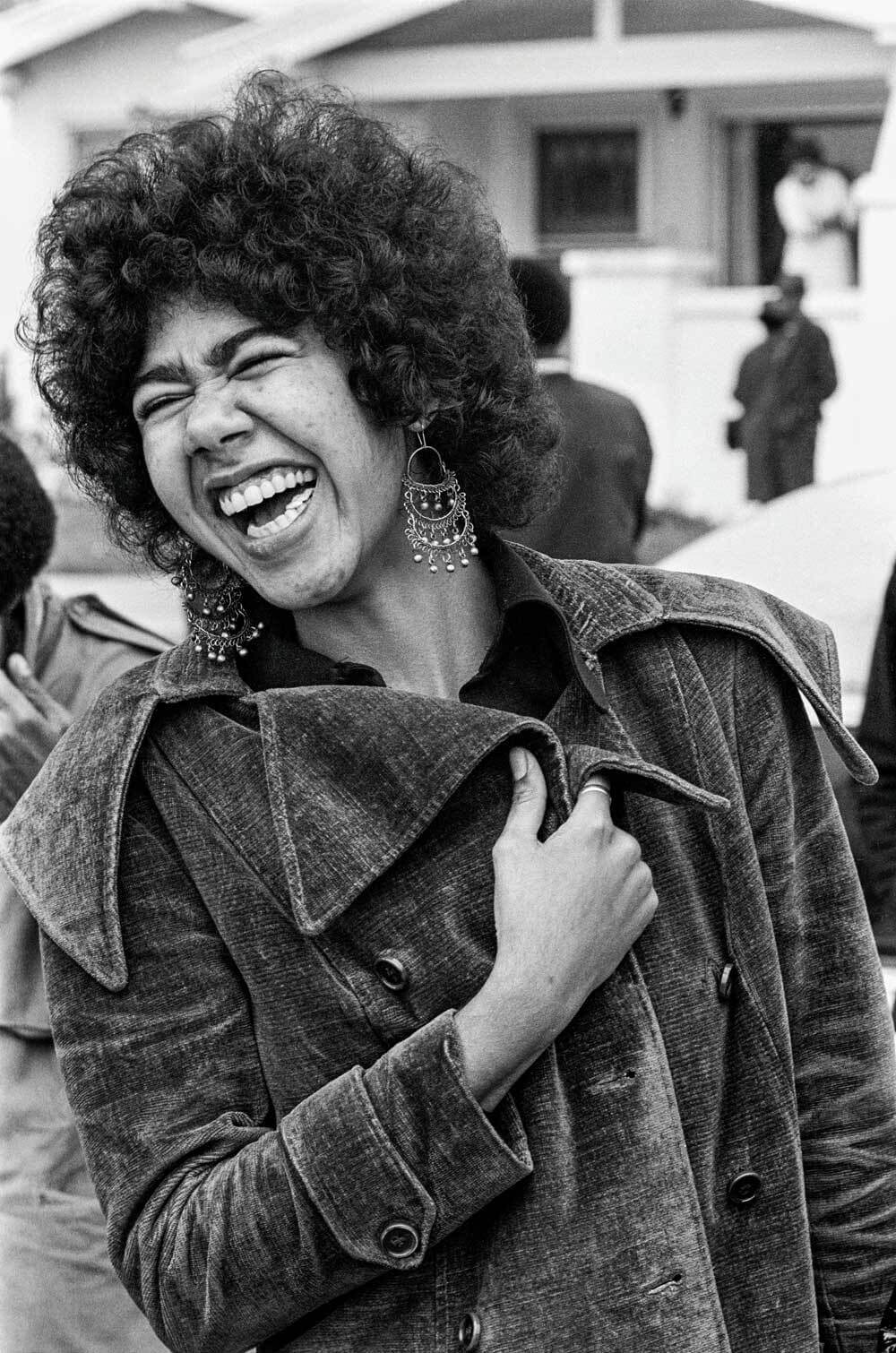

Oakland, CA, 1972: The author laughs with comrades after the Black Community Survival Conference. She served in the Los Angeles, New Haven, and Oakland offices of the party

Oakland, CA, 1972: The author laughs with comrades after the Black Community Survival Conference. She served in the Los Angeles, New Haven, and Oakland offices of the party

7 Women Recall What It Was Like to Be Part of the Black Panthers

“Hey, Panther Girl, Hey, Panther Girl!”

“When Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed in April 1968, I was a senior at Sacramento High. A palpable wave went through the Black students that day and many of us committed to the Party right then.

I was assigned to the Oakland BPP Community Center and occasionally worked at Central Headquarters, which was down the street. I also worked weekly at The Black Panther newspaper distribution office in San Francisco. At the West Oakland Community Center, we were a hub of neighborhood activity with lots of daily visitors—local, national, international—and lots of children. People in the community, neighbors, comrades, and our children: we were all a big family. Despite all we were going through, I felt loved and safe. Walking through the projects on my way to the laundromat (we had a free clothing program), I could hear people yell out from their windows and doors, ‘Hey, panther girl, hey, panther girl!’ I couldn’t see them, but they were watching out for us.” -Gloria Abernathy, Sacramento, Richmond, Oakland, and Berkeley Chapters, CA/the BPP Central HQ in West Oakland and East Oakland

Why Are My Cousins Always Going To Jail?

“I joined the party because the men in my family, who were serving this country in the armed services, came back and were arrested and always in and out of jail. I asked my grandmother: “Why are my cousins always going to jail?” They didn’t do anything. I loved my cousins. I looked up to them. They were the older men in the family. When I read the BPP newspaper and noticed that what I saw in TV interviews with Huey and Bobby mirrored the reality of the men in my family, it made me feel, there is a connection here. I can do something about this. I wanted to join the Black Panther Party. My grandmother preached that we should serve the people, and so I did.” -Katherine Campbell, San Francisco and Oakland Chapters, CA

Oakland, CA, 1973: Adrienne Humphrey testing for sickle cell anemia during Seale’s campaign for mayor of Oakland

Oakland, CA, 1973: Adrienne Humphrey testing for sickle cell anemia during Seale’s campaign for mayor of Oakland

Giving Your All To A Greater Good

“I was born in Bishopville, South Carolina. My earliest memory in life was sitting at the end of a cotton row, while my daddy and mama picked that row. Daddy moved us to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, when I was around 17 years old. That’s when I met a brother who told me about the Black Panther Party. I started going to political education classes. I learned what it meant to be willing to give your all to a greater good.

In the Winston-Salem Chapter, the most popular Survival Program was the Free Ambulance Program. We started it because, as we evolved out of segregation in the city, they closed the Black hospital. When they closed the hospital, people couldn’t get to the hospital way out on the other side of town. People literally died. The Party recognized what was wrong and addressed that wrong. We were willing to put our shoulders to the wheel to show our people that we can do things ourselves, without the system.” -Hazel M. Mack, Winston-Salem Chapter, NC

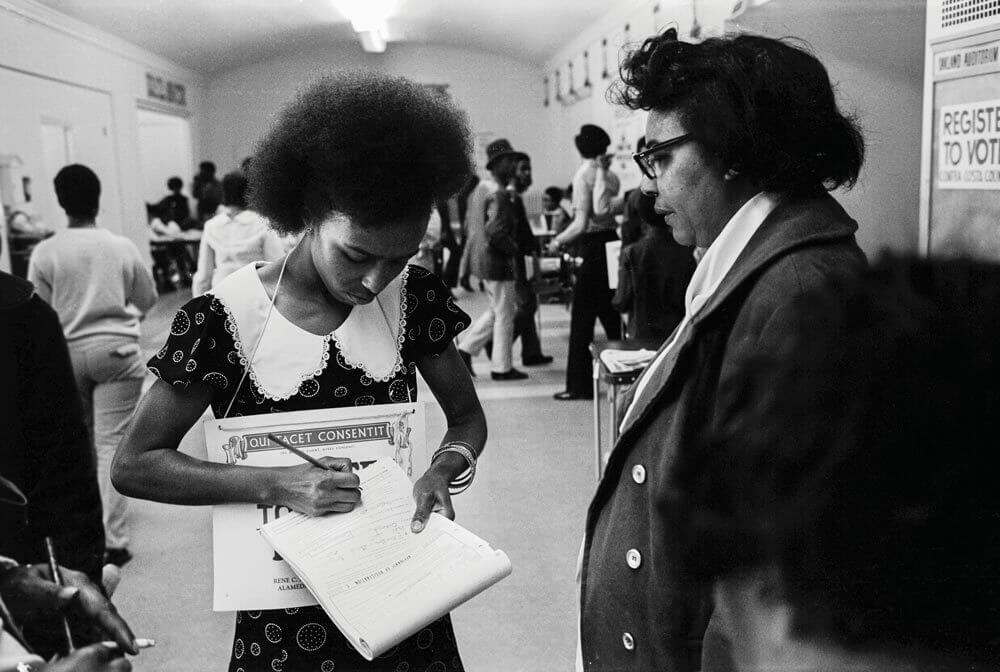

Oakland, CA, 1972: Gloria Abernathy registers people to vote during Bobby Seale’s campaign for Mayor of Oakland

Oakland, CA, 1972: Gloria Abernathy registers people to vote during Bobby Seale’s campaign for Mayor of Oakland

I Can Make A Difference In This World

“The day that Martin Luther King was killed, they called all the students into the auditorium, and we noticed that the few white children at our school were leaving, but we didn’t know that Martin Luther King had died. After the white children went home with their parents, they let us out. We were met by riot police with two-by-fours. They marched us back to the Haight and Filmore. If anybody stepped off the sidewalk, they got hit with a two-by-four.

I knew that day that I would be working for change in some capacity. I was only 13, but I knew that something was going to be different for me. Years later, I joined the BPP. I was 21. We worked 20 hours a day, and my focus was always on the Oakland Community School, from 1975–1982. [I remember] there was a little girl who we thought had hearing loss. I knew this child was not interacting with the other children. She seemed to float around the room as if things were going on around her, and not with her. I took her to the Children’s Hospital in Oakland for an exam, and found out that her ears overproduced wax. She said to me after the day they cleaned her ears, “I can hear, I can hear now!” It brings tears to my eyes just thinking about it. Once she could hear—oh boy, she was Miss It of that classroom. She was running things.

These experiences made me aware that I can make a difference in this world. I have spent the rest of my life trying to make that difference.” -Pamela Ward-Pious, Oakland Chapter, CA

Oakland, CA, 1972: Black Panther children in a classroom with their teacher, Evon Carter, widow of Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, at the Intercommunal Youth Institute, the Black Panther school

Oakland, CA, 1972: Black Panther children in a classroom with their teacher, Evon Carter, widow of Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, at the Intercommunal Youth Institute, the Black Panther school

This Country Ain’t All It’s Cracked Up To Be

“What drew me to the party was the raid on the [Black Panther Party] office in Los Angeles, December 1969. Al (Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter) and I had been married. I’d been resistant to the idea of becoming a member. I was a student at Cal State LA, I had my little boy, and we were just like the song say, movin’ on up.

After the SWAT raid, when they beat Al so bad and put him in jail, that got my attention. I understood what Al was trying to explain to me: This country ain’t all it’s cracked up to be. I helped out at the bombed-out, beat up office. I was majoring in physical education and minoring in math. Soon, I became the coordinator of the Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter People’s Free Medical Clinic at 3223 South Central Avenue.

You know, it’s not always about money. You want to make sure that you’re paid your value—don’t undersell yourself—but know that service is important. Sometimes you don’t have money to give, but maybe you have some time and some talent. We got to live together. We got to help each other if we’re going to make it through this.” -Norma Armour Mtume, Los Angeles and Oakland Chapters, CA

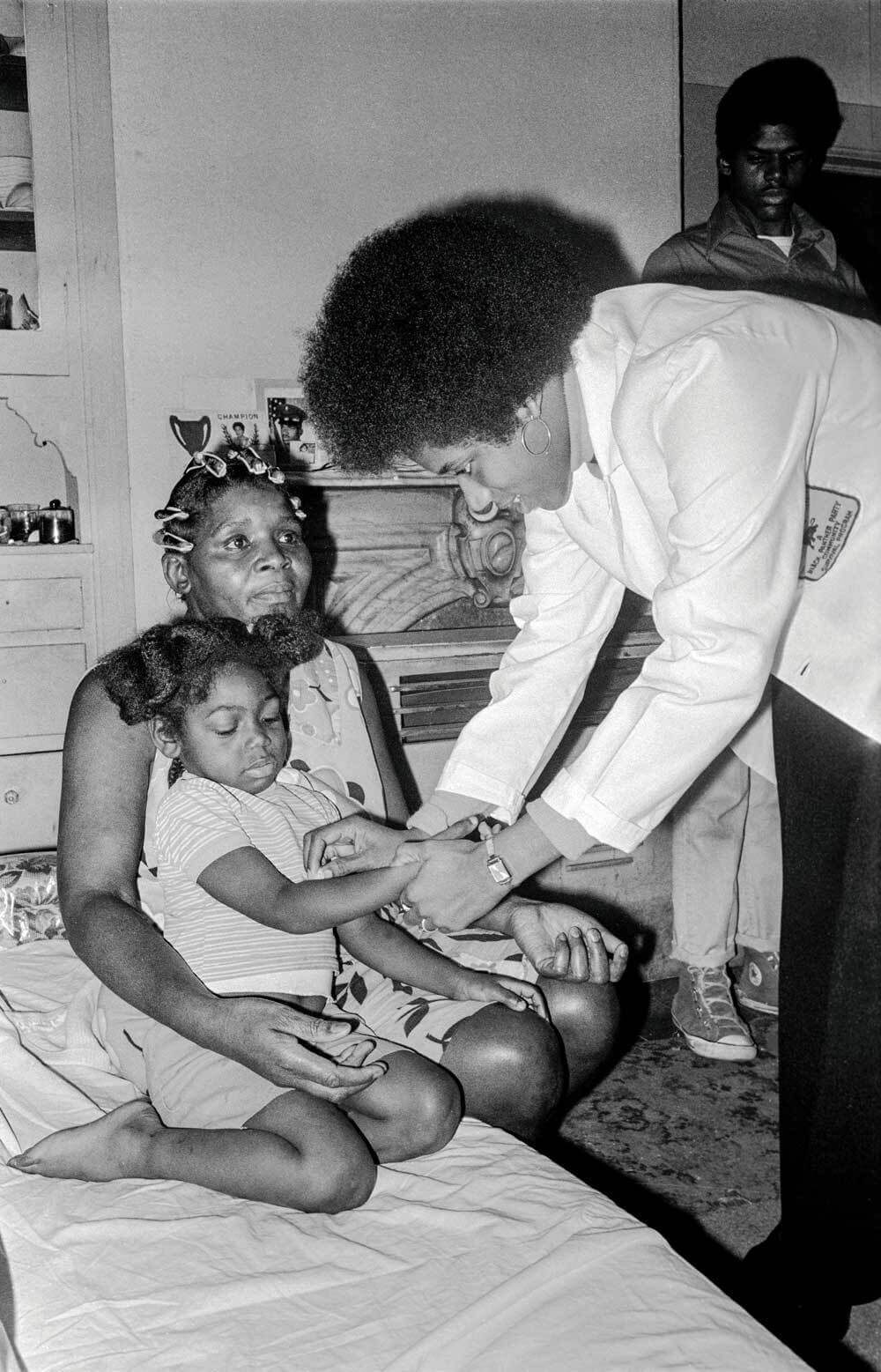

Oakland, CA, 1973: Norma Marmour Mtume from the George Jackson People’s Free Health Clinic cadre attends to a young girl during the Bobby Seale for Mayor campaign

Oakland, CA, 1973: Norma Marmour Mtume from the George Jackson People’s Free Health Clinic cadre attends to a young girl during the Bobby Seale for Mayor campaign

We Were All So Young

“I had many roles in the Party. I enjoyed being a typist for The Black Panther newspaper, and I was the first female Party photographer. Working at the school was really a highlight. At their former schools, the children from the community were considered “bad.” At our school, the children were considered as smart, with potential. I was reminded that their behavior changed because we really cared.

I’ll never forget the 10,000-bag food giveaway. I had no concept of how it would happen, of what 10,000 of anything looked like. When I think about it today—that we gave out 10,000 bags, with chickens in every bag! —that memory brings me so much joy. The thing is, we were all so young. We were a youth organization.

Young women today, you need to understand your history. Get your education but also make room for self-care. Joy comes with having family, friends, and connections in your community. You can’t do everything by yourself. You need others to live a healthy life.” -Lauryn Williams Jackson, San Francisco and Oakland Chapters, CA/Queens Chapter, NY

Oakland, CA, 1969: Angela Davis speaks at a Free Huey rally in DeFremery Park. In 1969 she had been a member of the BPP for one year and has remained a lifelong friend of the party

Oakland, CA, 1969: Angela Davis speaks at a Free Huey rally in DeFremery Park. In 1969 she had been a member of the BPP for one year and has remained a lifelong friend of the party

If We’re On This Earth, We Are Here to Serve

“One of my most memorable experiences is the Free Breakfast for School Children Program. No question. I mean—the whole idea of it! When our captain would pick us up, it was still before dawn. When we got into that van, I remember that the sky was doing that beautiful thing it does, before nighttime turns to daylight. I remember the way those children looked at me and all of us Panthers who fed them. It was love. I will never, ever, ever forget that.

Recently it occurred to me what givers we were; how spiritual it was for us to get up in the early morning to feed children. Nobody paid us. If we’re on this Earth, we are here to serve. I don’t think that we were sent here randomly.” -Regina Jennings, Philadelphia Chapter, PA/Oakland Chapter, CA

Top image caption: Oakland, CA, 1972: Testing for sickle cell anemia at the Community Survival Conference, photographed by Stephen Shames

Comrade Sisters by Ericka Huggins and Stephen Shames is published by ACC Art Books UK and can be purchased through bookshop.org.

All images courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery.