Hildegard of Bingen was a philosopher, a mystic, and a rebel, making history during a time when women were rarely considered worthy of such an honor. Here, noted historian Dr. Eleanor Janega peels back the habit on one of the Middle Ages’ most fascinating figures

Imagine waking up tomorrow as a young woman in Europe during the Middle Ages (the period after the fall of Rome, from around 476 to the end of the 1400s). Chances are you’d find yourself a peasant—or farmer—as about 85 percent of people in those years were. You’d likely be married, and depending on how old you were, you’d already have had a good number of children, as many as half of whom would have died before they were toddlers. Contrary to contemporary beliefs, you’d be clean—people took regular baths in those days—and you could look forward to living to about 70 or 80. Your days would be filled with hard work, including raising children, domestic chores, growing and harvesting food, and taking care of livestock. In fact, you’d have been working since childhood, so there wouldn’t have been a chance for you to get an education. Everything you’d learn, you’d learn at church, from a pastor who could read religious and philosophical texts—all written by men. That’s where you’d learn what you needed to know about women: that, like Eve, they were weak, they were sex-starved, and they were full of sin.

Now imagine, instead, waking up as one of the three percent of people of the period who weren’t peasants, but also weren’t royals. These were the nobility—think of upper-class people today. You would have likely been married off to a man—not one you loved, but one who could help secure your family’s political position or maintain their property. You’d also have plenty of children, many of whom would die, and while the peasants were growing all the food that kept you alive, you’d spend your days living it up, enjoying art, having fun at court, and wearing really nice clothes. You might have gotten an education, but you’d still get most of your learning from religious texts. And even as a noblewoman, you’d hold the exact same beliefs about women as peasants did.

It was into this world that Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098–1179), the most important medieval intellectual that you’ve never heard of, was born. Against all odds, she became a legend in her own time, and also in ours—in 2012, she was elevated to sainthood by Pope Benedict XVI. She was a scholastic powerhouse and the medieval equivalent of a triple threat in that she wrote religious texts, books about nature, plus music and plays. In her spare time, she also ran a nunnery that eventually got huge. Perhaps most importantly, she was able to challenge some of her society’s deeply held ideas about women.

Hildegard was born to parents who had already had either 8 or 10 children (who can keep track!), and by the time Hildegard came along they were surprisingly cool with the fact that she was the sort of kid who was having divine visions at the age of 3. As she’d later write: “From my early childhood, before my bones, nerves, and veins were fully strengthened, I have always seen this vision in my soul…it, rises up high into the vault of heaven and into the changing sky and spreads itself out among different peoples.” This was a lot for a little girl, and she kept much of it a secret. However, her interest in religion was obvious, and her parents were happy to encourage her.

“From my early childhood, before my bones, nerves, and veins were fully strengthened, I have always seen this vision in my soul.”

Ordinarily, girls from this level of society would get married off when they were in their early 20s. Since Hildegard was the youngest of a lot, her parents had already had a chance to make political deals through marriage. Plus, Hildegard was sick all the time, and it was likely that she would probably die in childbirth if she did get married, so, her parents decided that a religious kid was a good thing for them. Having a child stashed in a nunnery constantly praying for the family was a great way to make sure that God was on your side when you died. Besides, there was also a cachet to having a child in the church, proving that your family definitely was very holy indeed. But Hildegard’s parents didn’t want to send their daughter off to any old nunnery—they went for the holiest possible option, and sometime between the age of 8 and 14 (we don’t know exactly when; medieval records aren’t always super precise!) they sent her to live with Countess Jutta of Sponheim (1091–1136), who was an anchoress.

Anchoresses get their name from the Greek anachoreo, meaning “to withdraw,” and were women who decided that they were so dedicated to the religious life that they were going to give up the luxuries of the world completely by enclosing themselves in cells. When someone chose to be an anchoress in the German-speaking lands, the local bishop would come and say the Office of the Dead prayer cycle for them, emphasizing that for all intents and purposes they were no longer living. Anchoresses would have people bring them food, clothes, and bathing products. It was an incredibly difficult life, which was the point. The harder something was, the more it would, in theory, please God that someone was doing it. And the fact that Jutta was a countess (even fancier than Hildegard in the nobility stakes) meant that she was giving up a really nice life to live this way. As a result, she was pretty famous, and people would come show up to see her in her cell at the monastery of Disibodenberg to get her blessings or hear her speak. Hildegard’s parents wanted that kind of notoriety for their daughter, and so off Hildegard went to hang out with Jutta.

Jutta taught Hildegard the basics of literacy, which in the medieval period meant reading and writing Latin, but beyond that she didn’t have a whole lot to offer. Education for girls in this era was patchy. Most noble girls could read, but they often couldn’t actually write, as they employed scribes to do that for them. In addition to studying, Hildegard’s life in the monastery included doing a lot of nice things for her community like tending to the sick, singing psalms, and generally helping out around the place while Jutta stayed locked up. By the time Jutta died in 1136 Hildegard had been living in the cramped confines of Disibodenberg for 30 years, while the community of religious women ballooned around her. Jutta had been so famous that a lot of other women wanted to come and live alongside her. But increasingly, Hildegard, her star pupil, was becoming notable in her own right.

The monk Volmar (d. 1173) had come to visit the community repeatedly and thought Hildegard was really talented. He began assisting her with her education, but also working on her biography. He wrote extensively about how intelligent and holy Hildegard was and sent out letters about her to anyone who would read them. This was the medieval equivalent of having an agent, but for sainthood. If someone was really holy and you thought that they had a chance at becoming a saint, you needed to chronicle everything about their life to prove how great they were when the church came calling for explanations about why someone was so popular. This made people start paying attention.

With Jutta gone, the women needed a new magistra, which was the equivalent of what we would call a mother superior. Hildegard was unanimously elected to take control. Now it was her turn to decide who worked in the garden and who was in the kitchen. She assigned women to copy texts in the library, or to scrub its floors.

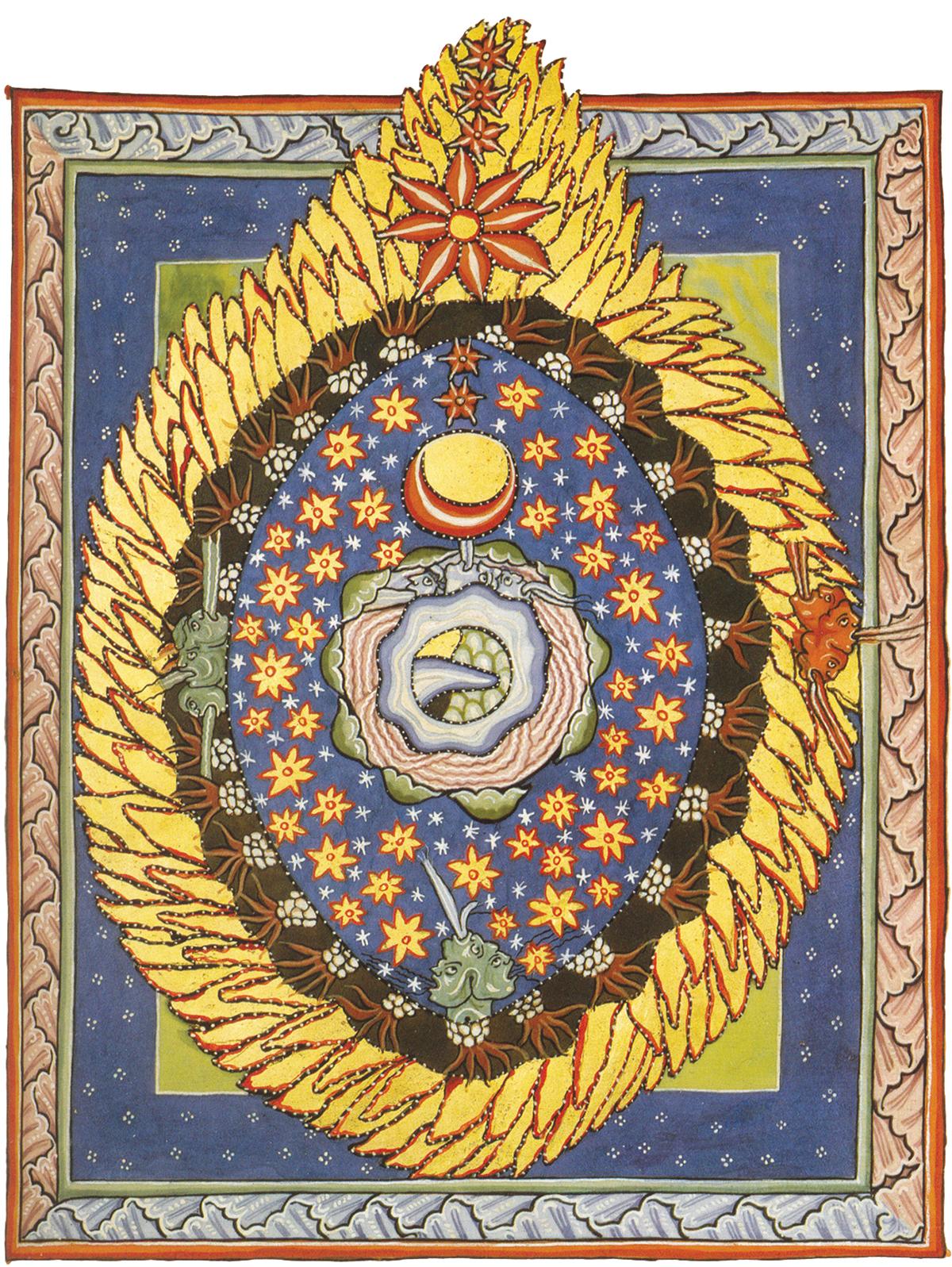

At the same time, Hildegard continued to have visions, which she believed came to her directly from God, but kept them to herself. “I heard and saw these things, because of doubt and low opinion of myself and because of diverse sayings of men, I refused for a long time a call to write,” she would later recall. But then, something changed. “And it came to pass…when I was 42 years and 7 months old that the heavens were opened and a blinding light of exceptional brilliance flowed through my entire brain.” Setting an example for late-bloomers everywhere, this is when she began working on her first, and probably most celebrated book, Scivias (Know the Ways), which she composed from 1142 to 1151. The Scivias was an illustrated manuscript in which Hildegard describes each of her divine visions, and explains their meaning. These explanations are absolutely key as without them, it isn’t always easy to understand what, say, the figure of a golden-winged woman with a scaly and monstrous face covering her pubes could mean. In all, Hildegard’s Scivias contains 26 of her visions and their explanations.

Saying that Hildegard “composed” Scivias is important, because while she was the one who had and explained the visions, she never actually picked up a quill and wrote them down. Since Volmar could write much better than Hildegard could he was also really handy to use as a secretary. In a world before the printing press, having a guy write out your ideas was how they started to circulate. After all, a book of visions was no good if no one actually read it.

The trouble with books like this was that the church took a pretty dim view of randoms popping up and saying that God was communicating with them. You never knew if you were dealing with a saint or a scammer, and Hildegard’s stuff was getting so popular that the church started to get suspicious. Now that there were actual books of hers being circulated, her reputation was increasing daily. Medieval Europeans absolutely loved religious literature, sermons—anything about God. Hildegard had a brand-new way of relating to all of that, which people were really into, and the church needed to know what this woman was doing over in her weird little cell community.

As a result, in 1148 Pope Eugenius III (c. 1080–1153) sent a delegation up to Disibodenberg to check in on Hildegard and establish whether she was producing material that the church could accept. They loved her. According to them, Hildegard’s visions were the real deal, and they felt that she should be allowed to continue her work unimpeded. So she followed up Scivias with the Liber Vitae Meritorum (Book of Life’s Merits, written 1158–1163) and Liber Divinorum Operum (Book of Divine Works, written from around 1163–1174).

Meanwhile, back in Disibodenberg, the community had become so enormous that Hildegard asked if she and the other women could move to their own nunnery in Rupertsberg, about 39 kilometers north of there. According to her, God had demanded this, but it’s probable that the uncomfortable conditions and some guy telling her what to do also played a part in both her and God’s decision-making on this one.

However, the abbot of the monastery, Kuno of Disibodenberg (died 1155), turned her down. He knew Hildegard was a star, and he wasn’t about to let her go easily. Think Britney’s conservatorship and you have an idea of what we’re talking about here. People came from all around Europe to see and talk with her, and when they did, they usually left a donation to the monastery. The Holy Roman Emperor wrote Hildegard letters. Even the papacy was sending delegations! There was nowhere for Hildegard’s fame to go but up, which meant that this was only going to make more money for Disibodenberg.

It’s at this point that God allegedly stepped in. According to Hildegard, God paralyzed her in retaliation. She could not move, she said, until she and her nuns were on their way to start their own community and that was that. Kuno got mad enough that he went and tried to physically drag Hildegard out of bed to prove her wrong. He failed, and suddenly he knew he was defeated. Having your prized resident lying on her back trash-talking you when visitors showed up was not the look that he wanted for Disibodenberg. He admitted defeat, and Hildegard miraculously found herself able to move once more. In 1150, Hildegard and her nuns were off to start their own brand-new community.

In their own space, Hildegard and the nuns gained even more followers. Volmar came to join them and got to work scribbling down Hildegard’s insights, including new ways of looking at classical Biblical themes—particularly in relation to women. While she agreed that, like Eve, women were weaker and softer than men, she argued that this meant their minds were sharper. Women were defined less by what their bodies could do than by what their minds were free to achieve without the burden of heavy flesh. Women were created by God, she believed, not as a worse sort of man, but as something new and different. Indeed, instead of accepting that men were at the top of a hierarchically ordered universe with women below them, Hildegard imagined creation as interconnected and harmonious. Sure, one sex might excel at some things that the other lacked, but that didn’t make one sex worse than the other.

For Hildegard, even when it came to procreation, women’s experiences were as interesting and important as men’s. In a work about fertility, she included the first description of a woman’s orgasm ever written in Europe. “When a woman is making love with a man, a sense of heat in her brain, which brings with it sensual delight, communicates the taste of that delight during the act and summons forth the emission of the man’s seed. And when the seed has fallen into its place, that vehement heat descending from her brain draws the seed to itself and holds it, and soon the woman’s sexual organs contract, and all the parts that are ready to open up during the time of menstruation now close, in the same way as a strong man can hold something enclosed in his fist.” It is an incredibly elegant way of explaining a complex sensation, and makes perfect sense in the context of her writing on the human body.

“In a work about fertility, Hildegard included the first description of a woman’s orgasm ever written in Europe.”

In fact, Hildegard’s focus on health and nature was so groundbreaking that she is considered the founder of what we call “natural history,” the precursor to science in the German lands. Her book Causae et Curae was the medieval equivalent of a bestseller, explaining what she saw as the connection between humans and nature and also giving health and beauty tips to readers. Of course, the section on how astrology effects various medical conditions might seem strange to us now, but this was a valid intellectual theory that had been held since the ancient Greeks, so we can’t really blame her. Besides, a lot of Hildegard’s herbal medical cures actually do work and have since been tried and tested, so it’s clear that she was using some of the results-oriented thinking that we now associate with the scientific method.

On top of all of this writing, Hildegard and her nuns also put on plays, and she wrote music for them to perform. Hildegard, like most medieval Europeans, saw music as a reflection of the divine. She wanted to make up to God for all the sinning humans had done, so she wrote anthems with gorgeous poetry to praise him, as well as various saints, the Virgin Mary, or to celebrate religious feast days. She often wrote about the experience of womanhood in her music, as well as some straight-up erotic songs addressed to Jesus as her husband and lover. Her biggest hits were her musical plays Ordo Virtutum and Symphonia. The music still bangs and is played today around the world. (Yes, there are even Spotify playlists.)

It’s hard not to be blown away by Hildegard and her achievements, but it’s also a reminder of why we don’t often get to hear about other incredible historical women. The world has always been full of intelligent, talented, amazing women, but not all of them were rich enough to be sent to live in a religious house and get a killer education, even if they were geniuses. They didn’t all attract some guy to write their story down when they weren’t taught to write themselves. When we remember Hildegard, then, we should also take time to acknowledge the vast numbers of forgotten women who could have achieved what she did given better support and fewer men literally trying to lock them inside for their own gain. Hildegard accomplished a lot in spite of her circumstances, but she’d likely also want us to remember the other women who we can’t hear about.

PHOTOS: OBELISK ART HISTORY

Top Illustration by Danie Drankwalter