Capturing everyone from punk pioneers to rap revolutionaries, iconic music photographer Janette Beckman is always pointing her lens toward the future

For over 40 years, British photographer Janette Beckman has been a fixture on the underground scene, creating a body of work that is stored deep in the memory banks of music fans everywhere. You may have seen her shots on the covers of seminal albums like the Police’s Outlandos D’Amour, New Edition’s Candy Girl, and EPMD’s Unfinished Business, or on singles like the B-52s’ “Love Shack,” Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car,” and Run-DMC’s “Mary, Mary.” One thing is for sure: Janette Beckman is everywhere.

Whether shooting music, fashion, portraiture, or documentary work, Beckman’s commitment to celebrating cutting-edge culture has made her one of the most important photographers of our time. But Beckman never rests on the success of her past achievements. Now 57 and living in New York, you can find her most recent work in the pages of Interview magazine, capturing up and coming female rappers. Or in the new Levi’s campaign—creating block party vibes for the new millennium. Whatever the case, Beckman is always in the mix, celebrating the spirit of rebellion, freedom, and self-determination that exemplifies the DIY culture that she has long helped shape.

Levi’s campaign, Brooklyn, 2017

Levi’s campaign, Brooklyn, 2017

How did you get into photography?

When I was young, I wanted to draw like David Hockney and go to art school. My parents did not want me to be an artist, but my mom let me go to St. Martins School of Art. I lived in a squat in Streatham, a suburb of London. We’d all sit around drawing each other, stoned in the basement. I then went to London College of Communication where I took up photography. That’s when I began to shoot people on the street. I became obsessed with August Sander’s book People of the 20th Century. I remember checking it out of the college library for so long that I didn’t dare take it back. As a matter of fact, it’s still sitting on my bookshelf. There was a lot in England to photograph during the 1970s. While I was in college, I discovered disco, punk, reggae, and rockabilly. Rebel culture was happening all around. England is very embedded in tradition. The monarchy and the class system are well in place. I was very attracted to punk—I thought it was going to change the country.

Boy George, London, 1981

Boy George, London, 1981

Tell me more about your early punk street photography.

When I came out of art school, there were all these exotic-looking people with mohawks wandering around. King’s Road was a big mecca for street fashion. There would be people hanging out in front of Town Hall drinking, and I would always find people to shoot. And whenever I went to shoot bands, there was always a lot of downtime. While I was waiting, I would turn my camera around to the fans. After a bit, I became more obsessed with taking pictures of the fans than the bands.

Mod Girl, London, 1976

Mod Girl, London, 1976

When did you start shooting musicians?

I started shooting for Melody Maker magazine in 1976. It wasn’t a problem that I was a woman; it was that I was an art student. They didn’t understand it. They were old rock guys who loved Led Zeppelin and wore jeans with cowboy boots, and I was there in Converse, pajama bottoms, and punky T-shirts. But the work got divided well—the editors weren’t that receptive to punk and I wasn’t into rock. The photo world is predominantly male, but for me, being female was positive. I’m not intimidating. I’m friendly. I’m chatty. I was never a groupie. I was there to take pictures, tell the story. When The Face magazine came out in 1980, I was in my element. The first issue had my photograph of the Islington Twins in their parkas. I could photograph the Alternative Miss World contest that artist Andrew Logan arranged where men came dressed in drag, I went to music festivals and illegal fight clubs in South London. It was all very casual and allowed me to shoot what I loved.

The Islington Twins, London, 1979

The Islington Twins, London, 1979

What made you decide to move to New York?

My first visit to New York was in 1975. It was around the time of the garbage strike. It was very cold and kind of great. My friend took me to the East Village, which was a desolate wasteland. It was so exciting. I came back in 1982 to visit that same friend on Franklin Street. She told me about an empty loft next door and asked if I wanted to stay for a bit. My window looked down on the alley where the Mudd Club was, and we’d always go to Dave’s Hot Dogs on Canal and Broadway after a night out. I was hanging out, meeting people, and getting work. I had a “What Went Wrong?” column in Mademoiselle where they showed photographs of fashion mistakes. Some friends started a magazine called Paper and I worked with them for the first five years shooting fashion and downtown celebrities. I was still working for Melody Maker and The Face; they knew I was in New York so they started giving me work.

Queen Latifah with artwork by Lady Pink, NYC, 1990/2016

Queen Latifah with artwork by Lady Pink, NYC, 1990/2016

How did you get into hip-hop?

The first hip-hop show I ever shot was in London in 1982 for Melody Maker. I got the assignment because I put my hand up—the writer said something like, “This is just a fad and it’s never going to last,” which is hilarious. Before the show, I went to the hotel and there were all these people looking really different from London’s dowdy punks. I started taking pictures that afternoon of Dondi, Futura, Rammellzee, Fab 5 Freddy, Afrika Bambaataa, GrandMixer DST—and I didn’t even know who they were! Then I went to the concert and it was just amazing. On stage, the double-dutch girls, the Rock Steady Crew, Fab 5 Freddy, and Afrika Bambaataa were all performing while Dondi and Futura were painting. We had never seen anything like it. Rapping, poetry, breakdancing, graffiti—it had all of this positive energy.

Female rappers [top row, left to right]: Sparky D, Sweet Tee, Yvette Money, Ms. Melodie; [middle row]: Millie Jackson, Peaches, a dancer for Sparky D; [bottom row]: a dancer for Sparky D, Roxanne Shanté, MC Lyte, Synquis, NYC, 1988

Female rappers [top row, left to right]: Sparky D, Sweet Tee, Yvette Money, Ms. Melodie; [middle row]: Millie Jackson, Peaches, a dancer for Sparky D; [bottom row]: a dancer for Sparky D, Roxanne Shanté, MC Lyte, Synquis, NYC, 1988

How did you re-connect with the hip-hop scene once you came to New York?

The Brits like to be ahead of everyone when it comes to music. Melody Maker and The Face started calling me to photograph this new thing called hip-hop. So I went to the Bronx to photograph Bambaataa, to Queens to photograph Run-DMC, to Brooklyn, and to Harlem. There was a new group called Salt-N-Pepa and I got the assignment to photograph them for Sky, a teen magazine. They came around my place on Avenue B. It was their first photo shoot. We were hanging out on the Lower East Side and they were just having fun. They liked the picture so they asked me to shoot their first record cover. They showed up wearing amazing leather jackets by [legendary Harlem designer] Dapper Dan. They introduced me to their manager, and he introduced me to other groups.

Run-DMC and their posse, Hollis, Queens, 1984

Run-DMC and their posse, Hollis, Queens, 1984

How did being an outsider work for you in that scene?

When I came to New York, being a British woman and going out to the Bronx, I didn’t know it at the time, but not being from here and not being a guy—as a white person going into African-American culture—really helped. They didn’t look at me as someone who had a bunch of preconceptions. I didn’t know what the South Bronx was like. I’d just jump on the train by myself with some film, one camera, and one lens. I didn’t know where I was going and what I was doing so I was fearless.

Camae aka Moor Mother, NYC, 2018

Camae aka Moor Mother, NYC, 2018

I’ve read that that when you first started showing your work to record labels, they were like, “It’s too rough!”

I had been working for The Face and Melody Maker and had shot important punk bands like the Clash and the Sex Pistols. I had done one or two album covers for the Police. I thought, I am going to go to New York with my portfolio and I will be the new Annie Leibovitz! So I started making appointments at record companies and they said, “It’s not really our style. It needs to be airbrushed and people’s hair isn’t combed, and you can see the zits on their faces. This stuff just doesn’t look right.” Then suddenly, I got my first record cover for the Fearless Four, a rap group, and I was like, Yes!

Your respect for the cultures you capture keeps you on the cutting edge. Tell me about the pictures you took of gangs in East L.A. in 1983.

I was staying with a friend in Los Angeles for the summer when I read a piece in LA Weekly about a gang in East L.A. I was fascinated and asked the writer to introduce them to me. We drove to a park in the neighborhood. I showed the gang members my photos of the British punk scene and asked if I could photograph them. It was like meeting a big family. They took care of me. I was invited to their homes, met their mothers and grandmothers and relatives. Everyone was telling me, “It’s really dangerous.” But I didn’t pay any attention. By the time [El Hoyo Maravilla, the photo essay containing those pictures] came out as part of an exhibition in 2014, about 90 percent of the people in those pictures were dead or in jail. It was really deep. I went out to Los Angeles and reconnected with three women I had photographed. They still lived in the old neighborhood, walking distance from each other. They were still tight. One works in gang rehabilitation; another works for the D.A.’s office; and the third works in human resources at a large company and drives a Mercedes. They survived and made it out of gang life.

East L.A. gang girls, 1983

East L.A. gang girls, 1983

Describe your vision as a photographer.

I am attracted to cultures and to people who are passionate about doing things in a different way. Collaboration is really important to me. Most of the musicians I photographed were not celebrities yet. They were just starting off. They were fresh and creative. We were at the same level and had the immediate collaboration thing. It’s about the culture and being a part of it.

You are consistent. Whether it’s punk or hip-hop or bike crews in the Bronx, you keep moving to the next thing that represents the culture.

I am lucky that I have my archive and I do shows. If I had been a fashion photographer back in the day, I wouldn’t be selling photos in a gallery. I just signed with the Fahey/Klein Gallery in L.A.

L: Protester at an anti-Trump demonstration, NYC, 2016; R: Protester at the Women’s March on Washington, 2017

L: Protester at an anti-Trump demonstration, NYC, 2016; R: Protester at the Women’s March on Washington, 2017

Congratulations! You know, what I love about what you do is that there is always a DIY element.

It must be my punk aesthetic. Making money has never been my primary thing. I’ve been lucky that I’ve been able to float through. Some really great things have come to me because people have respect for my punk and hip-hop work. I just shot for Levi’s, and they hired me to photograph block parties in Jersey City and Brooklyn. They got double-dutch dancers, breakdancers, kids on custom bicycles, and we were casting people off the street. In Jersey City, two old ladies came out. They were in their 80s, so we gave them director’s chairs and threw trucker jackets on them. I was like, This is it!

By Miss Rosen

All images by Janette Beckman

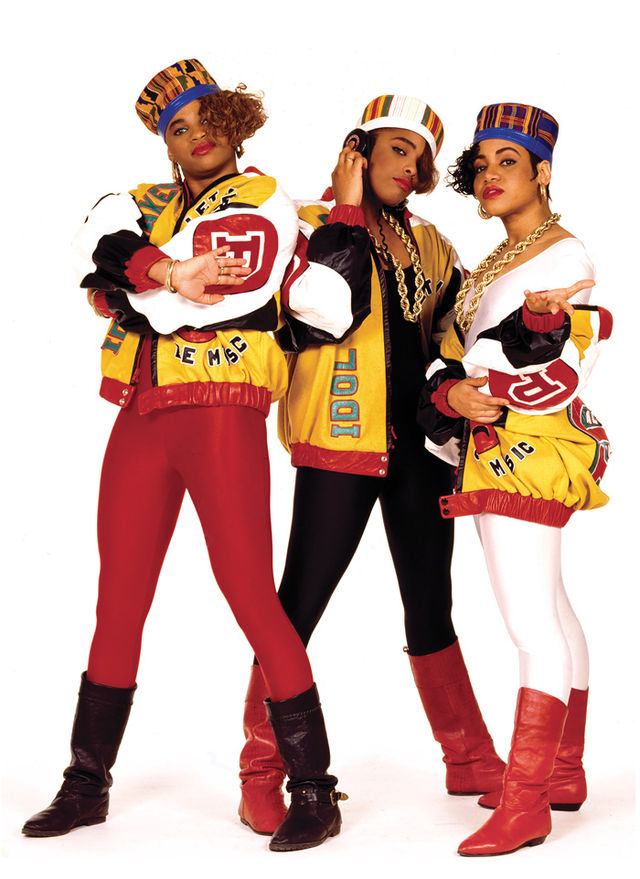

Top photo: Salt-N-Pepa, NYC, 1987

This article originally appeared in the April/May 2018 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

Photographer Amy Touchette Captures The Inner Lives Of Teenagers: Lady Shooters

Hey, Get Down! Women Got Down, Too

15 Photos Of ’90s Teens In Their Natural Habit: Their Bedrooms