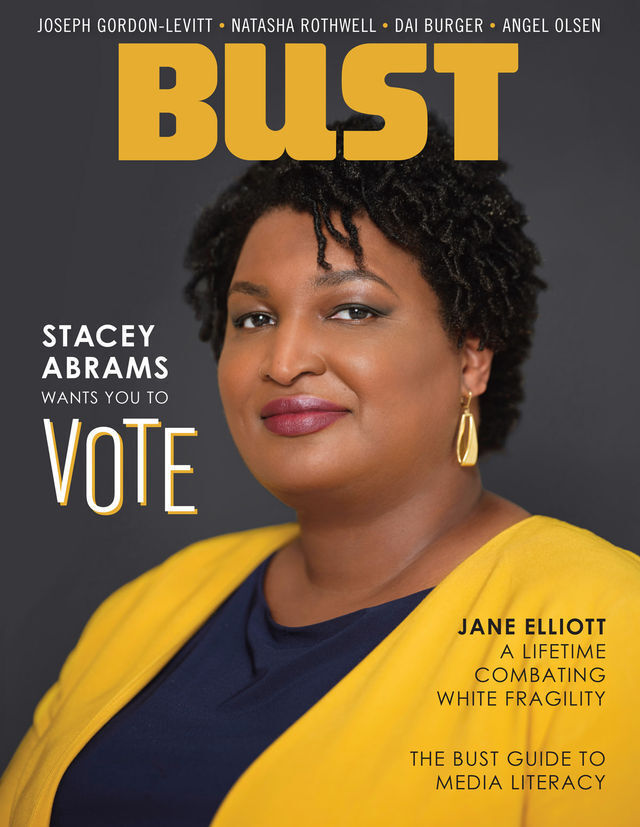

A rising star on the political scene, Stacey Abrams was cheated out of winning the Georgia gubenatorial race in 2018. Since then, she’s focused her efforts on protecting voters’ rights. Here, she talks with her friend, Amber Tamblyn, about the very serious threat to our presidential election—and what she plans to do about it.

The morning after 2020’s Super Tuesday election, I found myself waking up in a Florida hotel room, hung over with a half-eaten bag of Doritos by the bedside and a Le Tigre song still on repeat in my headphones. I checked my phone to discover in horror that I had texted Stacey Abrams in the middle of the night in a state of inebriated despair over the election results and where our country seemed to be headed. That afternoon, as my friend Phil and I boarded a flight back to New York, my phone rang. It was Ms. Abrams. I told her we were about to take off, and she quickly said: “Listen to me, before we hang up, I just want to say that everything is going to be OK. You’ll see. Things are changing. Trust me.”

Abrams, 46, has been involved in politics for over a decade, first by serving in the Georgia State House of Representatives from 2007 to 2017. But it was when she ran for governor of that state in 2018 that she became known on the national stage. As the Democratic candidate, she became the first-ever African-American gubernatorial major-party nominee—running against Republican Brian Kemp. (You may have heard a bit about him during the Pandemic times—he’s the genius who sued to block rules that would require people to wear masks in public.) When Abrams lost to Kemp by just 50,000 votes, she refused to concede, citing numerous election irregularities, which turned out to be true. In fact, in the years leading up to the election, Kemp had purged over half a million voter registrations—53,000 in October 2018 alone, 70 percent of which belonged to African Americans. By November of the following year, she still hadn’t conceded. “Concession in the political space is an acknowledgment that the process was fair,” she told Yahoo News. “And I don’t believe that to be so.”

I met and became friends with Abrams a few years ago, through our political and organizing work, and also our ties and mutual love for Atlanta, where my husband’s family is from. The character with which she has always moved through this world is something to behold. As a private citizen and a politician, she is both the arbiter of major change and the orbit around which change manifests. Americans look to her both as a leader and an educator. Abrams has always been deeply in tune with the distrust and divide between disenfranchised Americans and their government, and she’s been working to change that. There is a grace, a soothing, and a confidence with which she both takes care of what she believes in and brings that belief to fruition. For BUST, we talked about the trajectory of her most extraordinary and unique life, from her work with Fair Fight 2020—the voter registration organization she founded—to her upbringing to police brutality, and so much more. Stacey Abrams is not just teaching us how to fight for our right to truth. She’s also teaching us how to trust again.

Tell me a little bit about where you came from and how you got where you are now.

I was born in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1973. My mom was getting her master’s degree in library science and my father worked at the University of Wisconsin supporting her during her graduate studies. We moved to Gulfport, Mississippi, in 1976, where my mom became a college librarian and my dad worked at the shipyard. Their mission was to build a family that was stronger and had more opportunities than they’d had. My mom was the only one of her seven siblings to finish high school. My dad is the first man in his family to go to college, and even that was a struggle for him, because he was dyslexic.

So am I. That’s amazing.

When you couple untreated dyslexia with race, especially for a Black man in Mississippi in the 1950s—my dad found himself, despite accomplishing more than any other man in his family academically, living paycheck to paycheck.

My mom, in contrast, had the master’s degree from one of the top universities in the country. But because she was a Black woman, they were able to pay her only what they wanted. There were times when the college janitor made more money than she did, because there was no requirement for equal pay based on race or gender.

Stacey Abrams in elementary school

Stacey Abrams in elementary school

I have an older sister and four younger siblings; we grew up working poor. My mom doesn’t like that term, so she called it the “genteel poor.” We had no money, but we watched PBS and read books. She wanted us to understand that our economic circumstances would not dictate our capacity. She and my dad worked hard to make sure that we had the broadest set of experiences possible within the constraints of where we lived and what our resources were.

My parents were also very intentional about our education, about our faith, and about service. I grew up knowing those were my three jobs: go to church, go to school, and take care of each other. They didn’t simply tell us that this is what we were supposed to do; they showed us. They would take us to volunteer; they took us with them to vote. They wanted us to see their values in action. So that’s how I grew up. When I was 15, my mom and dad were both called into the ministry and so, at 40, they applied to graduate school in Georgia. That’s how I came to live in Georgia.

You said your parents wanted to “build a family that was stronger and had more opportunities than they’d had.” When I think about the work you’ve done, you could say that you’re trying to build a country of people who are stronger and have more opportunities than the generations before them had.

That started when I was young, when my mom and dad would take us to volunteer. I was unnerved by the fact that they thought two Black people and their six children were gonna fix Mississippi. I questioned where the other people were who should be doing this work. Not because I didn’t want to do it, but because it seemed deeply inefficient. And they said, “Government is people who are supposed to come together.” Basically, they were describing the social contract to me; how the way we live in America is in part through our government, but when it breaks down, it is our responsibility to hold the people we elect accountable.

I’ve always been driven to solve the problems in front of me, but also to anticipate what the next problem will be. And so, when the challenge was voter registration, I created the New Georgia Project to not just register folks for a single election, but also to create an organization that now, six years later, has registered nearly half a million people. When I faced the issue of voter suppression, it wasn’t enough to simply address voter engagement. It was: How do you create a national superstructure that can expand access to the franchise?

Would you say a lot of this was born out of feelings of frustration or anger? Especially about the 2018 gubernatorial race?

I started working on many of these issues when I was in college. I did voter registration and worked on youth poverty issues, civic engagement, environmental justice, and how to eradicate environmental racism. When I was in grad school, I worked in the community bank to think about how to create access to capital for small businesses owned by people of color who are usually pushed out of the banking system. As an entrepreneur, I started a company to work on this issue of creating access to capital. As a lawyer, I worked with nonprofits, especially disadvantaged groups that couldn’t afford to hire me. Each of these pieces has become a part of what I do.

In 2010, when I finally reached a level of political access as the Democratic leader in the state legislature, it gave me the ability to amplify many of the issues I had been working on. But I was also watching this naked, aggressive attempt by one party in the state to not simply hold power, but to diminish the likelihood of anyone else ever gaining that power. And that lived most directly through the work of Brian Kemp. The first time we clashed was when I started the New Georgia Project in 2014 to register voters. He did his best to silence those voters and block them from becoming active citizens. Prior to the 2018 election, I wouldn’t have called myself angry—I was determined, I was annoyed. But watching his gross disregard for citizenship and his blatant xenophobia—this is a man who ran commercials about rounding people up and deporting them, this is someone who used racist tropes—my outrage became just rage. Rage was new for me.

Eloquent rage, as [author] Brittney Cooper says.

Exactly. My way to speak my rage aloud was to create Fair Fight, Fair Count, and a lesser-known group called the Southern Economic Advancement Project. Because what Kemp explicitly denied was healthcare to Black and brown and poor people in Georgia. He explicitly denied us any action to address climate change which is ravaging our communities especially with high utility bills. When you’re used to a summer lasting three months and hitting 99 to 100 degrees, imagine when that becomes five months or seven months. So that rage became institutions for me. But this is not all about me fighting Brian Kemp. He is an avatar for a rot that exists in politics. A rot that says certain people are not just not worth the effort, but not worth the truth. And we see that same rot in Donald Trump.

We have the term Karen for a certain kind of white women, but I have been lobbying for “Brian” to be the man version of that. Hopefully that’ll take off at some point.

Yay, I like.

My husband David [Cross] is a lifelong Georgian; his whole family is there. He wanted me to ask you what’s being put in place to stop Republicans from stealing more elections.

In Georgia, we filed a lawsuit. And because of that lawsuit, they’ve made some changes to the registration challenges that we’ve had. But even though some good actions may be happening, worse actions are coming. The Republican National Committee, for the first time in 40 years, is going to be able to engage in paid voter intimidation across the country. Back in 1981, they had something called the Ballot Security Task Force. [These were] off-duty officers who wore armbands and had walkie talkies and sidearms. They went to predominantly Black and Latino voting districts in New Jersey and walked up and down the lines of voters, telling people that they would be monitored if they went inside to vote. These were police officers, so people got out of line. They thought if they voted, they could go to jail. It was so effective that the federal government issued an order against the Republican National Committee, and it lasted until 2017. For 40 years, their behavior was so offensive, the federal government was like, “Nah, y’all ain’t allowed to do this.” But in 2017, the federal court decided that [Republicans] had learned their lesson, and the Republican National Committee, with their hundreds of millions of dollars, could be trusted.

So now, they’ve organized a 60-million-dollar effort to suppress the vote in 2020, including hiring off-duty ICE officers and off-duty law enforcement. They are going to raise—using their language—an “army” of 50,000 poll observers, who will ask people in line, “Are you allowed to vote here?” We’re going to have millions of first-time voters in 2020, and they may get out of line and go home. So, we have to have a counter-army of volunteers in Georgia and around the country. That’s what Fair Fight is doing. For their 50,0000 “observers,” we’ve got 100,000 people of good will trying to make sure folks can either vote in-person or by absentee ballot from home.

Can BUST readers sign up to help with that effort?

Absolutely. We operate in 18 states and can direct them to the closest one at fairfight.com. We also need people to send out thousands of texts, which can be done from anywhere. We sent out hundreds of thousands of texts to help people navigate the voter suppression in the primary.

I want to talk about everything that’s been going on with the protests and police brutality. What are your thoughts on the state of things, and on defunding the police?

We have to reform how law enforcement happens because no matter what, there will always be some necessity to enforce the laws of our country; laws against child abuse, laws against theft. As someone who has a family member who has engaged in bad behavior, I believe that he should be held accountable and there should be rules that govern the practices and behaviors of those who were sent to enforce those laws. But we cannot dismiss the necessity of improved training; of eliminating qualified immunity; of outlawing and prohibiting chokeholds and other types of lethal force that aren’t necessary.

At the same time, we have to have a transformation of what we think law enforcement should be. Public safety means the public has to be safe, and sometimes that safety occurs long before a crime occurs. We have to fully invest in education, healthcare, and affordable housing. We have to eliminate food deserts. As I’ve said over and over again, a budget is a moral document. The priority should be to fund the things that make communities safe before crime intervenes.

“My outrage became just rage. Rage was new for me.”

For a while there was talk of you as Biden’s possible pick for vice president. And you really put yourself out there and said what it is that you want and what you think you’re capable of doing. It’s really inspiring. Has that always been a part of who you are?

There has been a grave mischaracterization of my conversations in the last few months about the VP slot.

Shocker!

It’s been portrayed as though I was campaigning for it, but that wasn’t what I was doing. I answer questions because I don’t have the luxury of assuming people are going to give me the benefit of the doubt. If someone says, “Can you do this?” I don’t get to just smile and hope they take my smile as assent. I’ve got to answer because they mean it when they say, “Can you?” They mean it when they say, “Will you?” And if I don’t say, “Yes, I can.” If I don’t say, “Yes, I will,” the presumption is going to be, “No, she can’t,” and “No, she won’t and let’s move on.” And that presumption will expand to cover anyone who looks like me.

What would Stacey Abrams of right now, today, want to say to yourself the morning after the [presidential] election? What would be the soothing words you would tell yourself?

I’d say I did everything in my power to defend, not just the right to vote, but the right of our people to be heard. And that I know I did that not only in the election, but also in those spaces where people couldn’t figure out how they were going to get from day to day. Then I would tell myself to take a nap, because there’s more work to do.

By Amber Tamblyn

Photographed By Lynsey Weatherspoon

Makeup by Paulette Morgan

This article originally appeared in BUST’s Fall 2020 print edition. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

Could The War On Drugs Finally Be Coming To An End?

What You Need To Know Now: Election Day Victories + Vote Counting Updates