Trump wasn’t the first to suggest a spoonful of disinfectant for all that ails you. At a White House coronavirus task force meeting in April 2020, the president wondered out loud if an “injection” of disinfectant could “clean” out the lungs and kill the coronavirus. That same month, the Poison Control Center reported a 121 percent increase in accidental disinfectant poisonings in the U.S.

Lysol immediately issued a statement after that April press conference stating, “As a global leader in health and hygiene products, we must be clear that under no circumstances should our disinfectant products be administered into the human body (through injection, ingestion, or any other route).”

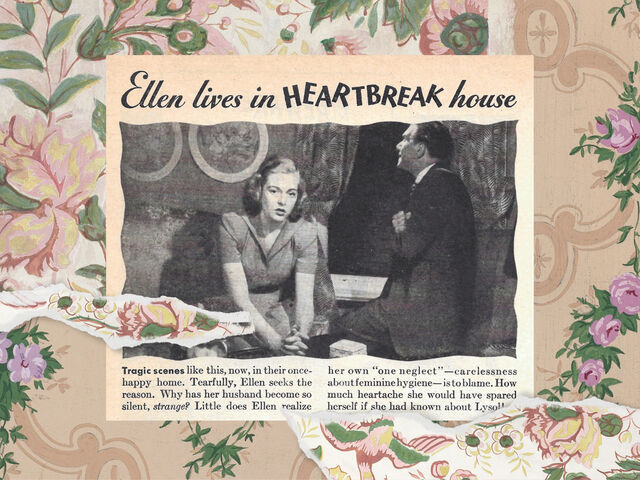

But in the early-to-mid-20th century, Lysol instructed American women to do just that. Before 1960, Lysol was widely marketed as a vaginal cleanser. Agonized women were the focus of an aggressive advertising campaign placed within the pages of popular magazines promising “immaculate internal cleanliness,” while assuring readers that “many doctors advise patients to douche regularly with Lysol just to ensure daintiness alone.” Lysol published portraits of adulterous husbands, weeping wives, and guilt-ridden mothers cradling their adult daughters while blaming themselves for not teaching them to douche diligently with disinfectant.

1945

1945

Sold like a pseudoscientific snake oil meant to cure all ailments, Lysol targeted insecure housewives with blunt assertions that their lack of adequate “feminine hygiene” was the reason their husbands were forced to stray. At first blush, these adverts read like standard, not-so-casual misogyny. But underneath the cheap pussy digs lay something even more insidious.

Hidden in plain sight in Lysol’s promotional materials was the word “germicide,” a term which appeared to be coded language for “spermicide,” especially when used in reference to a Lysol solution that could “spread” and “search out germs in deep crevices.” With the FDA not involving itself in matters of female troubles at the time, the brand had carte blanche to willfully mislead consumers into thinking that Lysol was a safe and effective option to help avert an unplanned pregnancy, something they claimed with veiled- yet-reckless abandon. This was done despite the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry of the American Medical Association cautioning disinfectant makers in 1912 against the dangers of encouraging customers to inject germicides into their genitourinary tracts.

Douching with Lysol after sex as a way to deter pregnancy may sound ludicrous, but according to historian Andrea Tone in her book Devices and Desire: A History of Contraceptives in America, it was the most popular form of birth control from the 1930s until the 1960s. This, despite the fact that no single ad ever specifically advocated the cleanser be used for that purpose. But women of the time understood the intentions of Lysol’s marketing materials—they were quite used to reading between the lines when it came to educating themselves about their sexual health and fertility. That’s because, in those days, presenting straightforward information about how to limit pregnancies would have actually been illegal.

This was all due to the Comstock Act, a set of laws passed by Congress in 1873 that classified all contraceptives as “obscene and immoral,” thereby making it a federal crime to disseminate birth control or any printed material that made reference to it. Not only did this broad information restriction rob the U.S. population of any reliable sexual health information, but it also made general gynecological resources unavailable, creating a culture where unscrupulous manufacturers like Lysol could freely capitalize on women’s fears.

1932

1932

Named after the legislation’s chief proponent Anthony Comstock—a special agent for the U.S. Postal Service who believed birth control was blasphemous and promoted promiscuity—the Comstock Act effectively suppressed the circulation of books, pamphlets, magazines, and any other information about reproduction or contraception through the mail or across state lines, and violators could face up to five years in prison for each offense.

Despite all his virtue signaling, however, Comstock was a chronic masturbator who likely received his erotica through the mail. We know this because his diaries are now a matter of public record, and within their pages he confessed that his addiction to masturbation afflicted him with unbearable guilt. Yet, he burned books, jailed suffragists, and elected himself the head of the morality police when he founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice: a group responsible for imprisoning people who wrote anything that he deemed impure.

Anthony Comstock

Anthony Comstock

Comstock did his best to ban bodies from public view, making it illegal for medical students to receive anatomy textbooks, seizing naked lady playing cards, and jailing writers of erotica. Show business legend Mae West was also one of Comstock’s conquests. She was imprisoned in 1927, given a $500 fine under the Comstock Act, and charged with “corrupting moral youth” for writing, directing, and starring in a Broadway play called Sex. Forcing himself on America, Comstock’s law oppressed women for nearly a century.

What a douche.

As a result, at the dawning of the 20th century, U.S. citizenry was desperate for sexual health information and nobody could legally obtain it. Lehn & Fink, however, the company that produced Lysol household cleanser, was more than happy to step in and fill this void in a way that toed the line but was careful not to cross it. To do so, Lysol developed a secret language, practically imperceptible by today’s standards, but one that communicated loud and clear to its intended audience.

“Mucus matter” was Lysol lingo for semen, the necessity of maintaining youthful daintiness alluded to avoiding the fullness of unwanted pregnancies, while “feminine hygiene” was a euphemism for birth control. Although today, “feminine hygiene” is known as an increasingly outdated term used when describing period-care products, pH disrupting douches, and hairless vaginas, according to historian Andrea Tone, the earliest roots of this phrase can be found in censorship laws. In the 1920s, advertisers coined the term to evade Comstock Laws while selling their jellies, foaming tablets, and floor cleaners as birth control. Of course, Lysol would never admit that. But if you interpreted it that way, so be it.

1953

1953

Starting in the 1920s, Lysol ran ads in every lady mag of the day featuring women mired in marital distress because of their vaginas. In the 1950s, Lysol’s riveting ad copy ran right alongside Pyrex cookware promotions and recipes for jellied lime and cheese aspic abominations, all designed to encourage readers to reach for the mid-century version of “living your best life.” From the hysterical to the long-suffering, formulaic female tropes were deployed in popular women’s magazines including Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, Redbook, and Screenland. Lysol spent millions placing suggestive messages in trusted newspapers and on local radio warning women that without Lysol, there was no hope.

Take, for example, the wording from this 1930s Lysol ad. “A familiar, pathetic figure—the wife who always gets tired and leaves the party before anyone else. So often it is her fault. No woman who has a normal foundation of good health can be forgiven for failing to stay young with her husband.” Translation: The loss of health, youth, and overall pep they’re talking about is the result of an unplanned pregnancy. This was a warning to women about the emotional toll a pregnancy would take on their marriage, and Lysol was sure to place the burden of birth control entirely on the housewife. They were seen as the main purchasers for the home so portraying them as completely responsible for all aspects of pregnancy prevention was a profitable approach for Lysol— an unfair expectation that still sticks today. Extorting feelings of fear from women put the brand in a position of power, which led to more hands reaching for their product.

They were also kind enough to provide young brides free access to the “Lysol Health Library” starting in the 1920s. Consumers needed only to send in a coupon and the books would reach them in a plain envelope free of charge. Titles included, Keeping a Healthy Home, Preparation for Motherhood, and of course, Marriage Hygiene.

1932

1932

Peeking inside the Marriage pamphlet clears up any uncertainty about Lysol’s intended use. In it, the company graphically compares the vaginal issues of an unwed woman to a wed one, claiming the genitals of wives contain “unclean secretions” (aka semen). “In the unmarried woman, this secretion is usually sufficient,” the text reads. “But with the married woman, the antiseptic douche should follow married relations as a cleansing agent.” When discussing the effectiveness of the antiseptic against germs (aka sperm), the pamphlet warned that its potency depends upon how promptly it was used after exposure to marital relations (sex). “Promptness is important.” Brides were also reminded that leaving pregnancy to chance and circumstance was a thing of the past. “The modern woman,” Lysol advised, “is leading a planned life.”

1934

1934

But readers didn’t just have to take Lysol’s word for it. The booklets also featured testimonials from several seemingly well-regarded female doctors to assuage women’s fears, all conveniently from foreign countries, making their credentials much harder to

substantiate. One page displays a photo of a studious-looking woman, supposedly a Parisian doctor or “Madame Docteur” curiously named “George Fabre.” The booklet claims Fabre is one of the most prominent gynecologists in France, even a knight of Napoleon Bonaparte’s Legion d’Honneur, the highest French order of merit. Yet, for all her groundbreaking credentials in the 1930s, there seems to be no record of Fabre or her contributions to medical science anywhere outside of Lysol’s library.

1932

1932

Another quoted source, “Dr. Nelly Stern,” claimed to have authored the German book Hygiene und Diätetik Der Frau (translated as Hygiene and Dietetics of Women). There is a book in print with the same title, however, it is authored by the former president of the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hugo Sellheim. Awkward, but not surprising, considering that all the way back in the 1930s, the American

Medical Association completed their own investigation and found that none of Lysol’s featured gynecologists in the company’s ads existed. But in an era when reliable sexual health information was illegal, women had little choice but to trust Lysol.

From pregnancy non-prevention to your husband’s infidelity, Lysol was there for you. Lehn & Fink even developed a disinfectant-doused tampon between the late 1930s and early 1940s treated with hydroxyquinoline—a potential carcinogen and mutagen depending on its chemical strain that, needless to say, probably shouldn’t be inserted internally via tampon. This “New Improved Tampon” (actual product name) touted its efficacy as “especially medicated for antiseptic and deodorant action” on its packaging. And if the consumer opted to unfold the instructions inside the box, she would be reassured in all italicized font that nothing “remains on top of the tampon that could possibly interfere with the normal menstrual flow.” Ahem, they’re talking about semen.

So, was there ever any truth to Lysol’s veiled claims that their disinfectant was an effective contraceptive? Unless killing the consumer counted as pregnancy prevention, then no, there was not. In a 1933 study conducted at Newark, NJ’s, Maternal Health Center, more than half of the women surveyed who claimed to be using Lysol as a contraceptive douche became pregnant. But despite its lack of effectiveness and side effects that included burning, blistering, bleeding, and most obviously, death, the toilet bowl cleaner/contraceptive became the best-selling (alleged) birth control in the U.S.

You might be wincing to yourself right now and possibly hoping that the Lysol of yesteryear used a milder formula than what’s contained in the bottles you’ve been using to safeguard your home from COVID. But tragically, earlier formulas were even more potentially harmful than those in use today. Lysol’s original formula contained a chemical called Cresol—a volatile substance derived from crude carbolic acid, coal, and wood—that burns and corrodes tissue. Skin contact with high levels can damage the kidneys, lungs, liver, blood, and brain, while ingestion can result in anemia, heart damage, coma, and death.

1953

1953

Of course, Lysol did everything it could to ignore the deaths that resulted from women douching with their product. Five deaths and close to 200 accidental poisonings were among those reported by 1911—the first decade of Lysol’s noxious internal use—alone. The mortality rate, however, was likely much higher. Luckily for them, Lehn & Fink had the financial means to silence and suppress the majority of suits brought against them by poisoned customers, and most, if not all cases against them were eventually thrown out.

Throughout the Comstock years, Lehn & Fink found themselves battling numerous lawsuits from customers alleging serious burns. But the company defended itself by claiming allergic reactions and careless consumer misuse were the cause of these injuries. In the 1935 case Kinkhead v. Lysol Incorporated and Lehn & Fink, court documents state that Ms. Kinkhead suffered burns as the result of using a diluted solution of Lysol despite following both the instructions in the package and Lysol’s “Marriage Hygiene” pamphlet. She asserted that she didn’t know there was any danger in using Lysol by following its directions since the only warning the defendants gave was that the product should not be used full strength internally.

Kinkhead’s defense maintained that the public has a right to use the product in accordance with its directions and not be harmed. Lehn & Fink disagreed and rebutted that “the plaintiff knew the solution contained in the bottle of Lysol was poisonous and that the label bore a skull-and-crossbones indicating that.” In 1941, the company was taken to court again for a case of vaginal scalding incurred by an anonymous Iowa resident. This time, their defense was that their directions “were in accordance with the requirements made of us by the Food and Drug Administration.” Though Lehn & Fink was never found liable, the company finally opted to remove the carcinogen Cresol from their formula in 1952. By this time, however, women had been using it for half a century while the corporation maintained that if you got burned, that was your own fault.

It wasn’t until the 1960s when Comstock Laws began to loosen that life-saving information became accessible. The pill may have been FDA approved in 1960 but it was widely restricted for years after and arguably still is. In 1965, in the U.S. Supreme Court ruling Griswold v. Connecticut, it finally became legal to distribute the pill in all states, but only to married women. Single women were denied access to this form of contraceptive protection until 1972 in America. To put that into perspective, Marilyn Monroe had been dead for 10 years before the reproductive rights of unwed women were recognized. It’s also worth noting that the Comstock Act has never been repealed.

Comstock’s ban on contraceptive materials empowered Lysol to market a toilet bowl cleaner as birth control. Their misleading advertising campaigns were enormously effective because the medical community had negligible interest in protecting or empowering women—and that sadly remains true today. Desperate women with little sexual health information and restricted access to birth control believed Lysol. Stuck between stigmas and superstitions, these women were told they were toxic, and some who followed the available guidance paid with their lives.

The enthusiastic sexism of Lysol’s highly effective ad campaigns serves as a startling reminder of the dangerous consequences of misinformation. Clearly, when access to reproductive health care is restricted, women’s lives are always at risk. As true then as it is now, accurate knowledge is power.

By Kelly Kathleen

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2021 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

The Surprising History Of Women And Pockets

Girdles May Have Been Uncomfortable, But They Sure Beat Corsets

Women, Wheels, And The Sexist Stereotype Of The “Backseat Driver”