Ranging from the desperately passionate to the treacly sweet, historical love letters are as informative as they are entertaining. But who amongst our favorite figures of the 19th century penned the most heart melting missives? Naturally, one would assume the honors for this would go to Byron, Keats, or Shelley. Their love letters were sublime, there is no doubt. However, if you have a yen to read truly smoldering love letters, might I suggest a gentleman who, when not busy conquering the world, expended his time writing scorching hot letters to his wife?

Napoleon Bonaparte was no romantic poet, but one would certainly not know it from his copious correspondence with Joséphine de Beauharnais. In February of 1796, one month before their marriage (and after being made Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Italy), he wrote the following:

“Seven o’clock in the morning.

“My waking thoughts are all of thee. Your portrait and the remembrance of last night’s delirium have robbed my senses of repose. Sweet and incomparable Joséphine, what an extraordinary influence you have over my heart. Are you vexed? do I see you sad? are you ill at ease? My soul is broken with grief, and there is no rest for your lover. But is there more for me when, delivering ourselves up to the deep feelings which master me, I breathe out upon your lips, upon your heart, a flame which burns me up ah, it was this past night I realised that your portrait was not you. You start at noon; I shall see you in three hours. Meanwhile, dolce amor, accept a thousand kisses, but give me none, for they fire my blood. N. B.”

Josephine de Beauharnais by François Gérard, 1800.

Josephine de Beauharnais by François Gérard, 1800.

Napoleon and Joséphine were married in March of 1796. Napoleon was twenty-seven years old and Joséphine was six years his senior. It was his first marriage and her second. One month after the nuptials, they were parted again. Napoleon wrote to her:

“…Every moment separates me further from you, my beloved, and every moment I have less energy to exist so far from you. You are the constant object of my thoughts; I exhaust my imagination in thinking of what you are doing. If I see you unhappy, my heart is torn, and my grief grows greater. If you are gay and lively among your friends (male and female), I reproach you with having so soon forgotten the sorrowful separation three days ago; thence you must be fickle, and henceforward stirred by no deep emotions. So you see I am not easy to satisfy; but, my dear, I have quite different sensations when I fear that your health may be affected, or that you have cause to be annoyed; then I regret the haste with which I was separated from my darling. I feel, in fact, that your natural kindness of heart exists no longer for me, and it is only when I am quite sure you are not vexed that I am satisfied. If I were asked how I slept, I feel that before replying I should have to get a message to tell me that you had had a good night. The ailments, the passions of men influence me only when I imagine they may reach you, my dear…”

“To My Sweet Love…” Napoleon’s Letter to Josephine, April 24, 1796. (Courtesy of Project Gutenberg.)

“To My Sweet Love…” Napoleon’s Letter to Josephine, April 24, 1796. (Courtesy of Project Gutenberg.)

The next month brought Joséphine another letter of note. This one is lengthy, but I include it here in its entirety to illustrate how consumed Napoleon was with both passion for his new bride and with doubt that she loved him as much as he loved her. Only imagine the length of this letter when handwritten! And the amount of time it must have taken for him to write it, when all the while he was on the brink of battle with two armies in motion. The letter reads:

“I have received all your letters, but none has affected me like the last. How can you think, my charmer, of writing me in such terms? Do you believe that my position is not already painful enough without further increasing my regrets and subverting my reason. What eloquence, what feelings you portray; they are of fire, they inflame my poor heart! My unique Joséphine , away from you there is no more joy away from thee the world is a wilderness, in which I stand alone, and without experiencing the bliss of unburdening my soul. You have robbed me of more than my soul; you are the one only thought of my life. When I am weary of the worries of my profession, when I mistrust the issue, when men disgust me, when I am ready to curse my life, I put my hand on my heart where your portrait beats in unison. I look at it, and love is for me complete happiness; and everything laughs for joy, except the time during which I find myself absent from my beloved.

“By what art have you learnt how to captivate all my faculties, to concentrate in yourself my spiritual existence it is witchery, dear love, which will end only with me. To live for Joséphine , that is the history of my life. I am struggling to get near you, I am dying to be by your side; fool that I am, I fail to realise how far off I am, that lands and provinces separate us. What an age it will be before you read these lines, the weak expressions of the fevered soul in which you reign. Ah, my winsome wife, I know not what fate awaits me, but if it keeps me much longer from you it will be unbearable my strength will not last out. There was a time in which I prided myself on my strength, and, sometimes, when casting my eyes on the ills which men might do me, on the fate that destiny might have in store for me, I have gazed steadfastly on the most incredible misfortunes without a wrinkle on my brow or a vestige of surprise: but today the thought that my Joséphine might be ill; and, above all, the cruel, the fatal thought that she might love me less, blights my soul, stops my blood, makes me wretched and dejected, without even leaving me the courage of fury and despair. I often used to say that men have no power over him who dies without regrets; but, today, to die without your love, to die in uncertainty of that, is the torment of hell, it is a lifelike and terrifying figure of absolute annihilation I feel passion strangling me. My unique companion! you whom Fate has destined to walk with me the painful path of life! the day on which I no longer possess your heart will be that on which parched Nature will be for me without warmth and without vegetation. I stop, dear love! my soul is sad, my body tired, my spirit dazed, men worry me I ought indeed to detest them; they keep me from my beloved.

Napoleon Bonaparte age 23 by Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, (1815-1884).

Napoleon Bonaparte age 23 by Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, (1815-1884).

“I am at Port Maurice, near Oneille; tomorrow I shall be at Albenga. The two armies are in motion. We are trying to deceive each other victory to the most skillful! I am pretty well satisfied with Beaulieu; he need be a much stronger man than his predecessor to alarm me much. I expect to give him a good drubbing. Don’t be anxious; love me as thine eyes, but that is not enough; as thyself, more than thyself; as thy thoughts, thy mind, thy sight, thy all. Dear love, forgive me, I am exhausted; nature is weak for him who feels acutely, for him whom you inspire. N. B.”

Napoleon at the Battle of Friedland by Horace Vernet, 1809.

Napoleon at the Battle of Friedland by Horace Vernet, 1809.

The frequency and fervor of Napoleon’s letters to Joséphine were not impacted by the toils and tribulations of a military campaign. He wrote to her even when he was exhausted both in body and in spirit. And his letters were anything but bloodless, perfunctory communications between a powerful man and his absent spouse. In the following excerpt, written at the end of a particularly dispiriting day, Napoleon begs Joséphine to write to him:

“Soul of my life, write me by every courier, else I shall not know how to exist. I am very busy here. Beaulieu is moving his army again. We are face to face. I am rather tired; I am every day on horseback. Adieu, adieu, adieu; I am going to dream of you. Sleep consoles me; it places you by my side, I clasp you in my arms. But on waking, alas! I find myself three hundred leagues from you.”

Interestingly, Joséphine does not appear to have written as frequently to Napoleon. When she did, her letters were often not up to the future emperor’s passionate standards. “I am not satisfied with your last letter; it is as cold as friendship,” he complains in one letter. He begs her to come to him soon, telling her that “fatigue and your absence are too much for me at the same time.” He even arranges an escort for her, proclaiming that:

“You will soon be beside me, on my breast, in my arms, over your mouth. Take wings, come quickly, but travel gently.”

Predictably, Joséphine continued to disappoint. Napoleon was a fearsome military leader, a man who inspired loyalty and devotion in countless others, but he never seemed to be entirely certain of how his wife felt about him. Though his own ardent letters were penned with regularity even as he marched across Europe, Joséphine was apparently often too busy to reply. “Joséphine, how can you remain so long without writing to me?” he asks in one letter. “Your last laconic letter is dated May 22.” In another letter, he commands her to send a reply at once, writing:

“Do not keep the courier more than six hours, and let him return at once to bring me the longed for letter of my Beloved.”

Portrait of the Empress Josephine by Firmin Massot, 1812.

Portrait of the Empress Josephine by Firmin Massot, 1812.

Another letter is signed with “A thousand kisses as burning as you are cold.” And in yet another he berates her for failing to write again:

“You, to whom nature has given a kind, genial, and wholly charming disposition, how can you forget the man who loves you with so much fervor? No letters from you for three days; and yet I have written to you several times. To be parted is dreadful, the nights are long, stupid, and wearisome; the day’s work is monotonous.

“This evening, alone with my thoughts, work and correspondence, with men and their stupid schemes, I have not even one letter from you which I might press to my heart.”

Another letter is much in the same vein, though a bit more reproving in tone:

“My Dear, I write very often and you seldom. You are naughty, and undutiful; very undutiful, as well as thoughtless. It is disloyal to deceive a poor husband, an affectionate lover. Ought he to lose his rights because he is far away, up to the neck in business, worries and anxiety. Without his Joséphine, without the assurance of her love, what in the wide world remains for him. What will he do?

“…Adieu, charming Joséphine; one of these nights the door will be burst open with a bang, as if by a jealous husband, and in a moment I shall be in your arms.”

Napoléon premier consul by François Gérard, 1803.

Napoléon premier consul by François Gérard, 1803.

In subsequent letters, he chides her for her indifference, telling her that he would prefer that she hate him than that she be cold to him. He alternately sends her thousands of kisses and fervent embraces, assuring her that “I love you passionately at all times.” Occasionally, he loses his temper, writing in one letter:

“I don’t love you an atom; on the contrary, I detest you. You are a good for nothing, very ungraceful, very tactless, very tatterdemalion. You never write to me; you don’t care for your husband; you know the pleasure your letters give him, and you write him barely half a dozen lines, thrown off any how. How, then, do you spend the livelong day, madam? What business of such importance robs you of the time to write to your very kind lover?”

Though even this angry letter is closed with the following heated wish:

“I hope that before long I shall clasp you in my arms, and cover you with a million kisses as burning as if under the equator.”

Napoleon’s letters to Joséphine are written with almost alarming frequency, many of them interspersed with the death and injury tallies of his men. One wonders that, considering her lack of response, he continued to write her so often and with such burning intensity. The jealousy in his letters is apparent – and with good reason. However Napoleon is not only jealous of Joséphine’s lovers, he is jealous of her Pug, Fortune. He writes:

“You ought to have started on May 24th. Being good-natured, I waited till June 1st, as if a pretty woman would give up her habits, her friends, both Madame Tallien and a dinner with Barras, and the acting of a new play, and Fortune; yes, Fortune! whom you love much more than your husband, for whom you have only a little of the esteem, and a share of that benevolence with which your heart abounds. Every day I count up your misdeeds. I lash myself to fury in order to love you no more. Bah, don’t I love you the more? In fact, my peerless little mother, I will tell you my secret. Set me at defiance, stay at Paris, have lovers let everybody know it never write me a monosyllable! then I shall love you ten times more for it; and it is not folly, a delirious fever! and I shall not get the better of it. Oh! would to heaven I could get better!”

Napoléon at the Battle of Eylau by Antoine-Jean Gros, 1808.

Napoléon at the Battle of Eylau by Antoine-Jean Gros, 1808.

Do all great military leaders write such wonderful love letters? What about the Duke of Wellington? Did Napoleon’s famous counterpart ever send a lady a million kisses that burned as hot as the equator? Sadly, no. According to Sir William Fraser in his 19th century biography, Words on Wellington:

“A real love letter of the Duke’s would be priceless. I cannot imagine his writing one. Lord Byron, who found it very troublesome work, copied his out of ‘Les Liaisons Dangereuses’; and whenever a fresh innamorata appeared on the scene, she unconsciously received facsimiles of previous epistles.”

The closest we get to love letters from the Duke of Wellington exist within the lengthy correspondence Wellington engaged in with Anna Maria Jenkins, known in her letters as “Miss J.” Miss J. was a young woman of about twenty years of age at the time she met the 65-year-old hero of Waterloo. She was also a bit of a religious zealot. Nevertheless, Wellington does seem to have developed an affection for her. He gave her a lock of his hair and sent her his likeness. He visited her. And over the course of nearly two decades, he sent her almost 400 letters. Many were letters of apology for some small offense he had given, such as failing to sign his letters with his full name instead of an initial.

Letter to Miss J. from the Duke of Wellington. (Image Courtesy of Digital Scholarship Services at Fondren Library, Rice University.)

Letter to Miss J. from the Duke of Wellington. (Image Courtesy of Digital Scholarship Services at Fondren Library, Rice University.)

According to Miss J.’s journal, Wellington clutched her hand and proclaimed his love for her upon their very first meeting. The letters from Wellington that followed, however, are as different from Napoleon’s love letters as night is to day. One of his earliest letters, written shortly after their first meeting, reads:

“London, Jan. 10, 1835.

“My dear Miss J.,—I have received your letter and enclosures. I beg to remind you of what I said to you the second day that I saw you; and if you recollect it you will not be surprised at my telling you that I entirely concur in the intention which you have communicated to me.

“I am obliged to you for what you have sent me; and I am

“Ever Yours Most Sincerely,

“Wellington.”

A bit dry, do you think? A bit bloodless? Perhaps. Though if one reads the bulk of the letters that Wellington wrote to Miss J., one can see that they follow a vaguely similar arch to those that Napoleon wrote to Joséphine. Wellington’s letters are never passionate, but they often verge on the irritable and almost teenager-like – ranging from letters bordering on intimacy to letters where (when angry) he writes to her in the third person.

Portrait of the Duke of Wellington by Sir George Hayter, 1839.

Portrait of the Duke of Wellington by Sir George Hayter, 1839.

There is also a long-suffering element to Wellington’s letters to Miss J. She never hesitates to upbraid him for some imagined offense, and yet the duke is rarely put out with her. In fact, the majority of the time Wellington writes to Miss J. apologetically, claiming he would never offend her as long as he lives. In the following letter, he responds to her complaints about how he has signed his previous letters as well as to her threats that she will return every letter he ever wrote to her. It reads:

“My dear Miss J.,—I always understood that the important parts of a Letter were its Contents. I never much considered the Signature; provided I knew the handwriting; or the Seal provided it effectually closed the Letter.

“When I write to a Person with whom I am intimate, who knows my handwriting I generally sign my Initials. I don’t always seal my own Letters; they are sometimes sealed by a Secretary, oftener by myself.

“In any Case as there are generally very many to be sealed; and the Seal frequently becomes heated, it is necessary to change it; and by accident I may have sealed a Letter to you with a blank Seal. But it is very extraordinary if it is so, as I don’t believe I have such a thing! You will find this Letter however signed and sealed in what you deem the most respectful manner. And if I should write to you any more; I will take care that they shall be properly signed and sealed to your Satisfaction.

“I am very glad to learn that you intend to send back all the letters I ever wrote to you. I told you heretofore that I thought you had better burn them all. But if you think proper to send them in a parcel to my House; I will save you the trouble of committing them to the Flames.

“Believe me Ever Yours most sincerely

“Wellington.”

I am no doubt doing a disservice to the Duke of Wellington here. He was an older man by this point. He was an Englishman and a gentleman with a very strong sense of the proprieties. He was writing to Miss J., a single woman who was young enough to be his granddaughter. To compare him to Napoleon, a young Frenchman writing to his wife, is probably unfair. Would their letters have read the same, all things being equal? I tend to doubt it. Frankly, even if he were young and writing to his bride, I cannot imagine the Duke of Wellington ever writing love letters that bear resemblance to those written by Napoleon Bonaparte.

In closing, I will just say that I often come across historical love letters in my research. And while there is certainly a lot to be said for the romantic missives of Keats, Byron, and Shelley, if you are looking for passionate inspiration for your novels (or your personal life!), I thoroughly recommend the writings of Napoleon Bonaparte. He may have lost the war to Wellington, but when it comes to romance, the Little Corporal still reigns supreme.

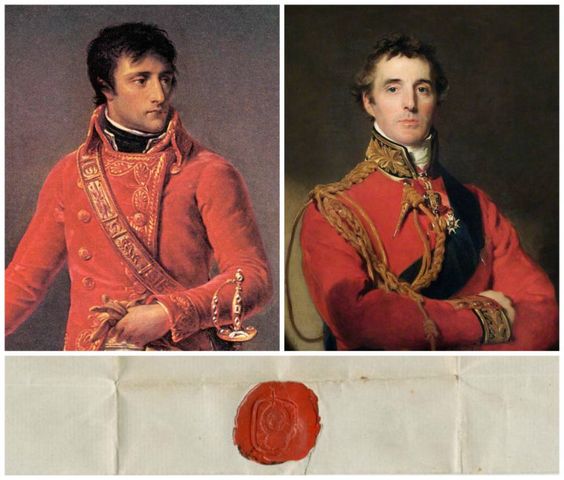

Top photo: Mimi Matthews

This article originally appeared on MiMiMatthews.com and is reprinted here with permission.

More from BUST

How Georgian And Regency Literature Shaped Society’s View Of Cats

BadRx: How Victorians Survived Cold Season With Chloroform, Garlic Syrup, And More

How The 19th Century Recognized Their Obligation To Proper Animal Welfare