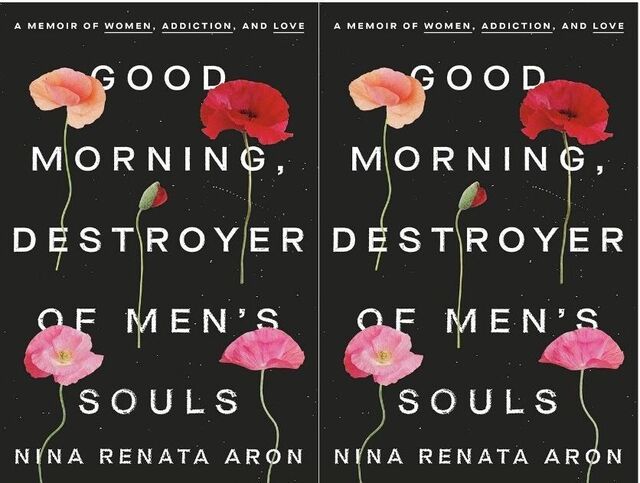

A lot has been written on the subject of addiction, but Nina Renata Aron’s unflinching memoir, Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls, tells a story often overlooked—the story of what it’s like to be in love with a person who struggles with addiction. Aron intersperses her own experiences with historical and psychological context, dispelling misconceptions about the temperance movement, Al-Anon, and codependence. Here, Aron and I spoke about her book, relationships, and motherhood.

Your book details the temperance movement, the history of Alcoholics Anonymous, and codependent theory. When you set out to write it, did you know you wanted to include so much historical context?

I think I imagined including even more. I imported what I needed into the book to contextualize my personal story. Personally, it was really useful to me, to frame my pain within a larger historical context and a larger story of women’s history, that was the thing that made me feel less alone. It was also being in recovery and being in meetings with other people who understood it. But it wasn’t until I unlocked this historical narrative that I felt like this is a thing that women have experienced for centuries.

You’ve corrected a lot of misinformation in the book. If you had asked me what I thought about the temperance movement before this book, I would have said nagging wives, all sorts of horrible things. I was shocked that I didn’t know the truth of this movement.

I agree. I am somebody who has always been interested in women’s history. I couldn’t believe how much more nuanced and interesting the movement was. It is definitely misrepresented and generalized, and I think it’s really funny and sad, but it’s a good example of, of history being written by men. This was a very dynamic movement of women of all ages, marital statuses, and it’s depicted like middle-aged, shrewish, party ruiners. Some of these women were really radical and it was a bona fide, massive social movement. I thought maybe I could get people to eat those vegetables, if I put it within the sexier story of this relationship.

Was there anything in your research that surprised you?

The biggest surprise for me was reading about the history of alcoholism and how it had been defined by the western medical establishment. And coming to understand that this condition called codependency was woven into the earliest understandings of alcoholism. And I talked about this in the book, but the codependent woman was referred to as the co-alcoholic at the beginning, and so it was kind of seen as this like, two-person condition. And it was always understood [in the form of] a heterosexual romantic partnership, or a marriage.

And that helps me really understand the ways that this thing that I have, we can call codependency has always been really gendered and has always been this sort of feminized condition. And when I started writing the book and thought, why don’t more people talk about this, why don’t people know more about this, that was sort of my answer. I was like, Oh, this was sort of the wives’ part of the disorder.

I could see how all of the tools that evolved to address codependency were started and then all these women gathered to talk shit about their husbands. And that became Al-anon. But they didn’t really feel entitled to have their own tools, their own approach, their own method: it was all just kind of like airlifted from A.A., and it’s still exactly like that. And so, in much the same way that I think there’s a lot of new recovery approaches and methods, and a lot of it’s bullshit in opinion, but I do think there are a lot of authentic attempts to reconsider addiction and recovery right now.

I was just thinking about the statistic from December showing 140,000 women specifically losing jobs, and it was making me wonder: how much art are we losing from women?

I’ve been thinking about that so much. I think that we’re losing more than we can possibly understand right now because I see those numbers and then I see all the tweets about those numbers that are like, “OMG!” I think so many women in my midst are grappling with not only losing our sort of sense of fullness as working people, because so many women I know right now are doing what I’m doing, like, you know, working with kids and virtual school and no playdates and no nothing, no sports, et cetera. And we’re all forced into this stay-at-home mom role. The other day, I woke up and my best friend who’s on the east coast had texted me, in all caps, I NEVER WANTED TO BE A STAY AT HOME MOM.

And then there’s the really profound sadness, of understanding that I don’t think the world gives a shit. Honestly, I don’t. It’s a reckoning with just how much hatred of women and willingness to rely on women to do all of the invisible labor to uphold the world persists. Help is not on the way.

I’d like to hard pivot to a piece you wrote in 2016, an essay called Fake Failures. Why Are Successful Young Women Writers Playing Miserable Online? I have been chewing on this idea all week. I’m obsessed with it. For one, I think this idea rolls over into working women in general. Two, I think this is happening subconsciously. And as a lesbian, my first thought was, I don’t see this phenomenon among lesbians and queer people. So, I think what you’ve discovered in this essay is a loophole for straight women to be successful and accomplished without committing.

I haven’t thought about that piece in a while. But really, I do think the thing that I was describing or trying to sort of characterize on that piece is very straight girl. I do feel like there’s this kind of disavowal of your own intelligence and success. Sort of like, no matter what you can’t step fully into your power, like you’re always hedging.

It’s a subconscious way to maintain being fuckable to men.

That’s the perfect distillation. It is a way to ensure that you remain non-threatening.

I have one last essay that I would like to discuss, On Why Middle-Class Parents Are Awful. I live in Park Slope and I’m a newish parent, so I felt this one deeply. I remember the first time my wife and I were strolling our son through the neighborhood and I felt so disconnected from all the parents. Where have you come in this journey? I know your kids are older now than when you wrote this. Do you have mom friends yet?

I do have mom friends. I could like talk about this all day, because I just find it so interesting. I always wanted to have babies. I always wanted to be a mom. But I find parent culture unbelievably lame. I always have, and so there’s been a level of alienation. And now my daughter’s nine and my son is about to turn 12 so they’re definitely in a different phase. I do think that I had to be patient because I tried engaging with moms at the very beginning. And granted, at the time, my life was like, you know, there was a lot of chaos in my life that made me feel so far outside of anything that like, the normal like middle class, upper middle class Bay Area moms could even wrap their heads around. Some were really voyeuristic about it and some more judgmental, but I think I sort of had to be patient enough to gain my own confidence as a mom and know that I was kind of doing it well enough.

And then I was able to sort of find the people who are like, to me, more normal, like slightly more broken, honest, depressed, just people who are more real about how challenging it is. And those have tended to be moms who are single moms, people who make a living in nontraditional ways, people who’ve been through some stuff.

I’ve also been found some comfort in knowing that so many people feel that way. I have lots of friends who are in those seemingly perfect marriages, and they have a beautiful house that they bought before they even had a baby. And they all feel profoundly alien. I think that people are alienated from an ideal. And there are a few assholes who are just lame people who are living their lives in pursuit of that ideal and don’t have a sense of irony, or, you know, whatever, those are weirdos. But I think most people, even if they seem totally normal, feel alienated because it’s just such a profound identity shift.

And I think that’s a rite of passage to have to reorient yourself. But it gets so much better. It’s like the culture shock of joining this lame club. And then you kind of have to go through your rebellion phase. And then it settles, and you get more used to the job. And then you find your people. I think that has been for me.

That’s great. I think that’s a nice, It Gets Better PSA.

Totally. Oh, my God, it gets so much better.

More from BUST

Genya Ravan’s “I Who Have Nothing” Melds Gold, Gravel, And Guts

Marlee Grace Helps Us Return To Self-Care In “Getting to Center”

Jaquira Díaz On “Ordinary Girls,” Home, And Telling Her Story: BUST Interview