On a Guadalajara street corner in Jalisco, Mexico, a woman wearing sunglasses, jeans, and Adidas crouches on the sidewalk, affixing a small black-and-white image of Dolores Huerta to a wall, colorful strings of yarn trailing from the labor activist’s sweater. The woman is Victoria Villasana, who has given her eye-popping embroidered treatment to everyone from pop culture legends like Grace Jones and Prince, to political figures including Donald Trump (vomiting bright green yarn) and Kim Jong-un (neon pink threads spilling from where his eyes should be), to everyday people—a woman making tortillas, a street musician holding a guitar. Her work has hung framed on gallery walls in Mexico City, London, and New York—she even created a piece for Rihanna. But Villasana’s pieces make their biggest impact on the street, where she began putting them up in 2014 while living in London.

After studying design in her hometown of Guadalajara, Villasana panicked about making logos and business cards for the rest of her life—“I didn’t like to have a lot of rules,” she says—and moved to London, where she began working as a florist, then in fashion. One day, she saw another Mexican artist putting up a small wheatpaste near her flat and was inspired to do the same. “It’s just paper, tape, glue, and yarn,” she says by phone from Guadalajara, where she now lives. But the result is much greater than the sum of its parts. “Whenever I do a piece, I don’t plan it, it’s from my heart and my stomach. I think there’s something that is not really me, maybe something spiritual, and that’s why people connect to it. Because honestly, I don’t know what it is.” In this interview, Villasana talks women’s work, “rebellious femininity,” and how a bit of yarn can provoke conversations.

“Mujer Eres Hermosa,” London, 2017

“Mujer Eres Hermosa,” London, 2017

“Tortillera,” Tulum, Mexico, 2018

“Tortillera,” Tulum, Mexico, 2018

“Being,” London, 2014

“Being,” London, 2014

How did you first decide to use yarn in your imagery?

There was a period of time when I really felt like a frustrated artist. You would come to my house and it was like coming to an art studio, because I would have all these half-finished projects. I was using creativity as a way to channel depression and negative emotions, so I was experimenting with so many materials. And then I picked up yarn, and I started doing stuff in a very abstract way with pictures. It just clicked.

Did you use yarn in a more traditional way before that? Are you a knitter? Did you embroider?

No, I don’t have any background like that. I see the works of people who embroider in the indigenous, traditional way—their work is astounding to me, the technique is incredible. I don’t see myself like that. Maybe my Mexican roots are there, but I feel like it’s my own spin.

Commissioned for the STARZ original series Vida, 2018; Chelsea Rendon photographed by John Tsiavis

Commissioned for the STARZ original series Vida, 2018; Chelsea Rendon photographed by John Tsiavis

Commissioned by Stance X Fenty, Rihanna, 2018

Commissioned by Stance X Fenty, Rihanna, 2018

Villasana in her studio, 2018

Villasana in her studio, 2018

Yarn is often thought of as a material of women’s work, and embroidery a feminine craft. Does that make you feel more connected to it, or do you feel like you’re subverting that image?

I feel like it doesn’t have the recognition because our grandmas knit. There is this history of women doing it, so it isn’t seen as an art form, or it doesn’t have the same value. Someone writing about my work said it was “rebellious femininity,” and I guess it is a way to connect with my femininity, on my own terms, because I’m always drawn to more masculine things.

I don’t want art to just be pretty; I want people to connect with my art in other ways. I think this medium resonates with most people, even men, because it creates this connection in our brains to our grandmas, or women in our lives who have nurtured us. [The material] inspires this empathy, and it’s cross-cultural.

Your art has gotten very political. Do you consider it a platform for your views?

I don’t want to be political, and I don’t want to create art that separates people, because what is happening in the world right now is a lot of separation. One of the first pieces I did in London was this image of refugees with colorful yarn. And I did it because there was a lot in the news about refugees; I feel like we hear so many numbers—not just about refugees, but in general—that with all this bad news, we are kind of normalizing poverty, or we’re normalizing violence. We hear it so much that we are starting to not act on it at all. When I created this image, with color and with yarn, I wanted to make this connection. I don’t think it’s that political. I just think that I want to talk about it, or I want people to open up and to start a conversation.

One of your signatures is leaving yarn that hangs off the image, or even out of the frame. Is there a purpose behind that?

I really like the sort of surrealistic, unfinished look of it, and also because the movement of the yarn with the wind makes it seems like it’s alive. It’s like the environment finishes the piece, not me. And I love when it’s coming out of the frame; it has no control. That’s my personality: You can’t put me in a box.

By Lisa Butterworth

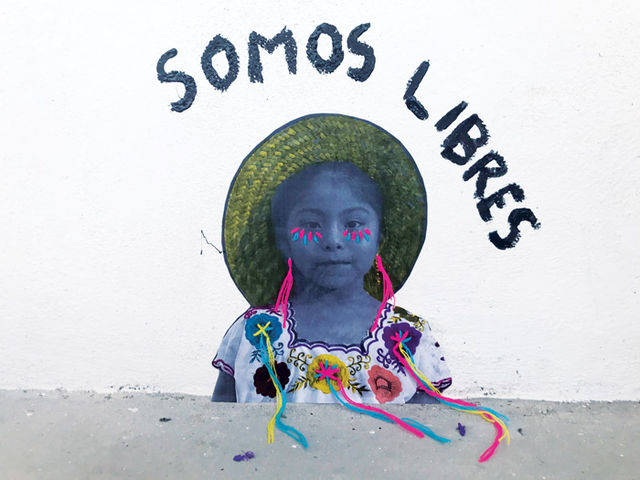

Top photo: “Somos Libres,” Tulum, Mexico, 2018

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2018 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

This Art Showcase Is Displaying The Intersectionality Of Identity

A Woman Created One Of The Most Iconic Art Pieces Of All Time—But A Man Took Credit For It

6 Women Visual Artists To Get Obsessed With