During the 18th and 19th century, patent medicines were everywhere. These various powders, potions, elixirs, and cordials were primarily peddled by quacks, some of whom purported to be doctors from respected universities like St. Andrews in Scotland. The claims they made on behalf of their products were extraordinary. According to advertisements of the era, a restorative cordial or tonic could do practically anything, from curing dropsy in children to curing impotence in men and hysteria in women. Some even proclaimed that they could cure a fellow of the desire to engage in that “solitary, melancholy practice” so common to the male sex (i.e. masturbation).

One of the most popular patent medicines of the late 18th and early 19th century was Dr. Brodum’s Botanical Syrup and Restorative Nervous Cordial. Advertisements and testimonials for this miracle product abound. Some of the advertisements were quite lengthy. The following appeared in an 1802 edition of the Lancaster Gazette. I have included it here in its entirety so you have a general guideline of the promises made by these types of medicines. It reads:

“How many men, to all appearance in the prime of life, who have not yet arrived at the age of twenty-five years, are rendered miserable to themselves, and useless to the great chain of society, which they have either brought on themselves, or, by the force of bad example, are given up to a SECRET VICE; the consequence is, that their mind as well as body is debilitated; to those the Nervous Cordial is recommended, and for which, Dr. BRODUM obtained his Majesty’s Royal Letters Patent; it will protect them from the infirmities of old age, and a wretched dissolution. Amidst the agonizing reflections of conscious guilt, how many are there of both sexes, that are deterred from entering into the married state, by infirmities which delicacy forbids them to disclose; and those are not a few, who, being already married, are rendered miserable for want of those tender pledges of mutual love, without which happiness in this state is at least very precarious. The vice above alluded to, causes, in women, irregularity, pains in the back and chest, hysterics, spasms, loss of appetite, &c. In men, it causes imbecility, languor, relaxation, nervous complaints, debility, anxiety, and a long train of melancholic disorders. The Nervous Cordial stands unrivalled, as it has been analyzed by the first professors and medical men Europe can produce, and may be relied on in giving immediate relief and certain ease in most stages of nervous complaints, this exalted medicine has been productive of general good; and the many restored to blessings of health, from the gates of death, by this inestimable preparation, is the highest eulogium which could possibly be paid to Dr. Brodum, and is, indeed, his boast and reward.”

William Brodum by E. A. Ezekiel, 1797. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.)

William Brodum by E. A. Ezekiel, 1797. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.)

Dr. Brodum does seem to focus quite a bit on solitary, secret vices. This is not as bizarre a concern as it sounds. In the mid to late 19th century especially, actual medical doctors believed that masturbation led to an endless catalogue of health problems. In his 1894 book The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs, Dr. William Acton refers to masturbation as a “melancholy and repulsive habit” that is “degrading and debilitating to the child” and injurious to the adult. He advises that rather than engage in this “secret sin,” a gentleman occupy himself with vigorous exercise. He also quotes the advice of a clergyman on dealing with this unhealthy impulse, writing:

“[If a] man is tormented by evil thoughts at night. Let him be directed to cross his arms upon his breast, and extend himself as if he were lying in his coffin. Let him endeavor to think of himself as he will be one day stretched in death. If such solemn thoughts do not drive away evil imaginations, let him rise from his bed and lie on the floor.”

As you can see, especially in the Victorian era, religion, morality, and physical health were inextricably tied together. A “sinner” or one who indulged in vice was often believed to suffer the ill effects in his constitution for years to come. Knowing that, it is no surprise that many patent medicines targeted both the physical symptoms as well as the nervous or mental ones. This was a canny marketing technique. After all, when it came to the urge to indulge in a solitary, melancholy practice, it was much easier to take a spoonful of cordial than to be vigorously exercising all day long. Although, considering that the cordial was also supposed to treat impotence, I am not sure what the end result would have been for our hapless patient.

The Quacks, 1783. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.)

The Quacks, 1783. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.)

But Dr. Brodum’s Restorative Nervous Cordial was not only advertised as an aid to sexual dysfunction. It was also touted as being able to cure serious illness. To this end, there are many testimonials in newspapers of the era. The following, appearing in a January 1800 edition of the Ipswich Journal, reads:

“A child belonging to Mr. Molyneux, of this place, had been afflicted, for a considerable time with a very dangerous dropsy in the head, which threatened inevitable death, and was thought absolutely incurable by several very respectable gentlemen of the faculty. After trying a great variety of means, recommended by different friends, he was at last induced to try Dr. Brodum’s Nervous Cordial, by taking a very few bottles of which, the child was, to the astonishment of every one, restored to perfect health.”

These advertisements and testimonials had little to do with the truth. In his book Aphrodisiacs: The Science and the Myth, author Peter V. Taberner explains that advertisements of the era were usually filled with “puffery” or exaggerated claims for a product. He writes:

“A few played upon the fears and gullibility of the readers by telling them that they were suffering from major disorders that could only be treated by the medicine in question. Assuming that a sufficient number of hypochondriacs would respond to these advertisements, success was assured. A particular feature of all these advertisements was the grandiloquent style of language that was employed. What the copy lacked in scientific accuracy was amply compensated for in literacy hyperbole.”

The Quack Doctor’s Prayer by T. Rowlandson after G. Woodward, 1801. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.)

The Quack Doctor’s Prayer by T. Rowlandson after G. Woodward, 1801. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.)

Were these quacks really doctors? And were their elixirs really analyzed by the “first professors and medical men” in Europe? In general, no. For an example of a garden-variety quack, we need look no further than the background of Dr. Brodum himself. A scathing article in the 1805 edition of The London Medical and Physical Journal titled “Of Quacks and Empiricism” set out the facts of Brodum’s life, writing that not only was Dr. William Brodum not a doctor, but that he was not even William Brodum. His real name was Issachar Bear Cohen. The article states:

“We announce that he was born in Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark; in the streets of which he early exercised a public profession, that of hawking and selling ribbons, similar to some of his brethren in London, who dispose of shoe-strings in every avenue near the Royal Exchange.”

In 1787, at the age of twenty, Cohen migrated to London where he went into the service of Dr. Lamert–purveyor of Switzer’s Balm. However, rather than assisting in Lamert’s medical pursuits he was employed in “going on errands” and “taking care of Lamert’s horse.” He adopted the name of Dr. Williams and, according to the article in The Journal:

“Finding Williams a smart active youth, very loquacious, and of sonorous lungs, [Lamert] procured him boots and spurs, and mounted him á cheval, to circulate far and near the virtues of Switzer and other nostrums.”

Parker’s Tonic Advertisement,1850. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.

Parker’s Tonic Advertisement,1850. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.

It was while out hawking Switzer’s Balm that Cohen/Williams met a widow who esteemed him very highly. She lived in a town where an apothecary by the name of Brodum had recently died. The widow encouraged Cohen/Williams to take the name of Brodum. She also gave him a smart set of clothes. Not long after, the man now known as William Brodum was admitted as a partner in Lamert’s business where he began to represent himself as a surgeon who had served in America with the Hessian army. But Brodum was not satisfied with being a mere surgeon. He had an eye toward becoming a physician. As luck would have it, at that time in history, The Journal declares that at St. Andrews:

“…the professors have been in the practice of conferring the degree of doctor of medicine, without the least examination, or personal knowledge of the candidate; but merely on the recommendation of some respectable physician.”

After finding such a physician to recommend him, Brodum was appointed a Doctor of Physic by St. Andrews. The Journal writes that no sooner had Brodum acquired this honor than:

“…he threw off the mask, and appeared in his own character of a quack doctor, screened by a degree acquired by falsehood and deceit; and which he has ever since impudently published with his respective quack bills.”

Cocaine Toothache Drops Advertisement, 1885.

Cocaine Toothache Drops Advertisement, 1885.

What Brodum lacked in medical knowledge, he made up for in “the science of knowing the weakness of human nature.” Passing himself off as a “learned graduate of the University of Aberdeen” (a place that he had never seen before in his life), Brodum rapidly rose to fame and fortune peddling his Nervous Cordial. The Journal asserts that:

“This medicine was chiefly the old formula of the decoction of the woods, consisting of sassafras, guaiacum, and a few other articles, which [Brodum] procured of Mr. Chamberlin, an eminent chemist in Fleet Street. The decoction is well edulcorated with sugar or molasses, and sold at six shillings and sixpence a bottle, or one pound two shilling for five bottles.”

Brodum’s income in 1805 was estimated at five thousand pounds per annum and he was known to own “the most superb carriage in the metropolis,” in which he rode through the streets “in the midst of a gaping and admiring multitude.” He was a convivial man, a true salesman, and was widely liked not only for his Nervous Cordial, but for the generous donations he made to worthy causes – donations for which he made sure he was always credited in the newspaper.

Why in the world, you may ask, would anyone ever purchase Dr. Brodum’s Restorative Nervous Cordial? Wasn’t it obvious that it was nothing more than quackery? Didn’t the public realize that Brodum was an uneducated street peddler with no medical training? The fact is, that the poor and working class of the early 19th century were not likely to have read the exposé in The London Medical and Physical Journal. Many could not read at all. They would have had no way of knowing that Brodum was a fake.

Instead, imagine how impressive a patent medicine created by a doctor with a degree from a prestigious university must have seemed. And also consider that such medicine was, in many cases, comparatively cheaper than summoning and being treated by a real physician (*According to Sally Mitchell’s book Daily Life in Victorian England, the usual price of a doctor’s visit at the end of the century was five shillings).

Carters Little Nerve Pill Advertisement, Circa 1870 – 1890.

Carters Little Nerve Pill Advertisement, Circa 1870 – 1890.

We must also allow for the aforementioned “sufficient number of hypochondriacs” and the legion of bored, unhappy people suffering rather vaguely from “nerves” for whom patent medicines were particularly appealing. There is another layer to this as well which speaks more to gender issues of the 19th century and that is the prevailing view that women were delicate, frail creatures. I have heard the argument made that unidentifiable illness and regular attacks of the vapors were a way of a lady rebelling (or exercising her power) within the confines of suffocating societal constraints. To that end, patent medicines were just another weapon in her limited arsenal. Of course, some, like Jane Austen in her unfinished 1817 novel, Sanditon, attributed hypchondria and reliance on patent medicines to nothing more than a combination of boredom and a desire for attention. She writes:

“Disorders and Recoveries so very much out of the common way, seemed more like the amusement of eager Minds in want of employment than of actual affliction and relief.”

Patent medicines in the form of powders, elixirs, and cordials would remain popular throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th. Today, we require truth in advertising and there are governmental agencies to regulate the sale of medicines. Big Pharma has largely replaced the potions of yesteryear. Even so, you have only to watch a late night infomercial advertising a weight loss drug or virility aid to recognize that the age of pharmaceutical quackery is far from over.

Advertisement for Obesity Soap, circa 1903.

Advertisement for Obesity Soap, circa 1903.

This article originally appeared on MimiMatthews.com and is reprinted here with permission.

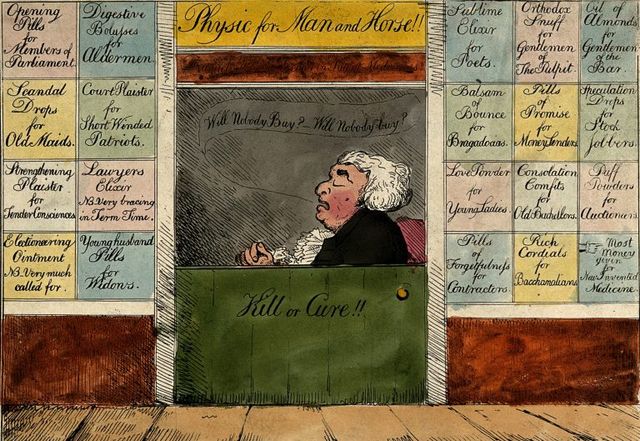

Top photo: Quack Doctor Open for Business by G.M. Woodward, 1802. (Image Courtesy of The Wellcome Library, CC BY 4.0.)

More from BUST

6 Healing Podcasts To Listen To For Self-Care

This DIY Face Massage Will Make You Glow Inside And Out

The Horrifying History Of Hair Dye