100 years ago, the 19th amendment, allowing women the right to vote, was passed. But although the amendment was written to give women of all races the right to vote, in practice, it was mostly white women who secured the right; Black women would have to wait nearly 5 decades more to actually exercise that right.

You’ve probably heard about many of the women involved in this fight, but it wasn’t won in one fell swoop. Instead, it was a battle that was fought state by state, much like our current election process. In order for the amendment to pass, at least 36 states had to ratify it. Was your state one of those? If it was up to them, would you be allowed to vote this November? Read on for our guide to the history of women’s suffrage in every one of our (then) 48 United States.

The Northeast

Maine

Like many states in New England, Maine was a hub of suffragist activism early on. Prominent suffrage leaders frequented the state to encourage the movement throughout the 1850s, including Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, and sisters Ann Frances Greeley and Sarah Jarvis. Although Maine’s movement was largely organized by wealthy white women, factory workers also stood up for their right to vote, marching with banners demanding the “Right of Suffrage to Every American Citizen.” However, Maine suffragists faced repeated losses thanks to the all-male legislature, forcing many women to turn their efforts towards passing the federal amendment. It wasn’t until November 5, 1919, did Maine finally vote in favor of women’s suffrage, ratifying the 19th Amendment.

New Hampshire

The suffrage movement in New Hampshire was host to many fiery activists, including the infamous Marilla Marks Young Ricker from Dover, who marched into a local polling place in 1870 and demanded a ballot as a property owner and tax-payer. Although she was turned away that day, she continued the tradition for five decades. She also ran for governor of New Hampshire in 1910, but because she could not vote, she was illegible. She knew this would happen, but said she wanted to “set the ball rolling. There isn’t a ghost of a reason why a woman should not be governor or president if she wants to be and is capable of it.” Thanks to the work of Marilla and many other suffragists, New Hampshire officially ratified the 19th Amendment on September 10, 1919.

Vermont

Vermont was a cradle of suffragist activism from the beginning. Fueled largely by the Vermont Equal Suffrage Association (VESA), founded in the early 1880s, the movement sent representatives to the National American Woman Suffrage Association and the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage to push for suffrage action at the federal level. From 1885-1920, Vermont held annual statewide suffrage conventions for which they decorated their towns with banners and flags and engaged in festivities. Although the Vermont Legislature passed full suffrage for women in 1919, the presiding pro-liquor-anti-suffrage-governor, Percival Clement, vetoed it. It wasn’t until February 8, 1921, did Vermont’s Legislature finally ratify the 19th Amendment (needless to say, Vermont women promptly voted Clement out of office).

Massachusetts

Massachusetts was one of the central loci of women’s suffrage–and not just wealthy white women’s suffrage. The state held the first National Women’s Rights Convention in 1850, hosting abolitionist and suffragist speakers such as Sojourner Truth and Lucy Stone; and Boston hosted the first American Equal Rights Association meeting, which sought equal rights and suffrage for both Black Americans and women (which later split into two rival national organizations). Activists in Massachusetts stopped at nothing to get their voices heard, with more than 150 ending up in prison for protesting. Despite male voters’ attempts to squash the suffrage movement, Massachusetts was the eighth state to ratify the 19th Amendment on June 25, 1919.

New York

When activists Jane Hunt, Lucretia Mott, Martha Wright, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had tea together one fateful July day in 1848, the seeds of the women’s suffrage movement were planted. The five women organized the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY. In the following decades, women marched, protested, and lobbied for their suffrage rights. However, their movement was not inclusive of Black women, who were forced to march separately from white women in suffrage parades. However, the movement wouldn’t have ignited without the legendary Sojourner Truth, an enslaved woman from upstate New York, whose speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” inspired suffragists all over the country to engage in the movement. New York officially ratified the 19th Amendment on June 16, 1919.

Connecticut

The major organization lobbying for suffrage in the late 1800s in Connecticut was the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA), founded by Frances Ellen Burr and Isabella Beecher Hooker. However, they weren’t the only activists: in Hartford, prominent activist Mary Townsend Seymour was concerned that the 19th Amendment would not include Black women and made sure to fight for their inclusion with the Colored Women’s League of Hartford and the Hartford Chapter of the NAACP. Connecticut ratified the 19th Amendment officially on September 14, 1920.

Rhode Island

Rhode Island has had a long history of resistance from its disenfranchised citizens, beginning with Dorr’s Rebellion in 1842 when rebels fought to expand suffrage beyond male property owners and their eldest sons. In the twentieth century, Rhode Island women adopted the cause of suffrage and built their own movement, helping to finance national suffrage campaigns and lobby U.S. Senators. It was only after decades of relentless activism did the state ratify the 19th Amendment on January 6, 1920.

Pennsylvania

The history of Pennsylvania’s suffrage movement, as is the case with many other New England states, grounds itself in the work of abolitionists. The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, for example, held one of the earliest women’s rights conventions in 1854. Philadelphia is also home to some of the most well-known suffragists such as Lucretia Coffin Mott, who organized the Seneca Falls Convention in New York with Elizabeth Cady Stanton; and Charlotte Grimké, a Black anti-slavery activist, poet, and educator. Due to unrelenting activism (including some unconventional approaches, such as the Justice Bell), Pennsylvania ratified the 19th Amendment on June 24, 1919.

New Jersey

While most women had to wait until 1920 (or later) to vote, some New Jersey women and free Black Americans could vote as early as 1776. New Jersey’s first constitution in 1776 gave voting rights to “all inhabitants of this colony, of full age,” and in 1790, the legislature reworded the constitution to include “he or she.” (Excluding married women, who could not own property). Unfortunately, the patriarchy found out about this and stripped women and Black Americans of their voting rights in 1807. It wasn’t until more than a century later of devoted activism did women get their voting rights restored on February 9, 1920 — but this didn’t necessarily include Black women, who didn’t explicitly get free access to the polls until the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Delaware

Suffragists in Delaware meant business. Mabel Vernon, one of the leaders of the National Women’s Party, organized local protests and nationwide tours. Also an accomplished public speaker, in 1916 she led a group of activists who displayed a banner and trolled President Wilson while he was giving a speech to Congress.

Annie Arniel was one of the first suffragists jailed in June 1917 for picketing the White House. She was recruited by Mable Vernon and Alice Paul to work for the NWP. She served a total of eight jail terms for suffrage protesting and a total of 103 days. While picketing once, she held up the famous banner that read: “As our boys are fighting for democracy abroad, is it a crime to ask for democracy in our own country?”

Florence Bayard Hilles was perhaps Delaware’s best-known NWP activist. Born into a prominent political family in Delaware, Florence Bayard Hilles devoted herself to suffrage in her home state and for her home state. Thanks to the work of these key figures as well as other dedicated suffragists, Delaware, while late to the party, showed its support for women’s suffrage on March 6, 1923, by ratifying the 19th Amendment.

Maryland

Maryland, in contrast to its geographic bedfellows, was a hub of suffragist activity. And their approach was far from standard: they set up booths at county fairs, drove decorated cars through parades, and even sailed a suffrage boat in a town regatta. Suffragists from Maryland also embarked on ‘suffrage hikes,’ campaigning around the state in decked out horse-drawn wagons. While in many parts of the country the suffrage movement was largely segregated, Maryland washost to integrated suffrage organizations such as the Progressive Women’s Suffrage Club in Baltimore, which sought enfranchisement for all women in the state. However, despite all this activism, Maryland male voters shot down the ratification of the 19th Amendment. It wasn’t untilMarch 29, 1941 (after a brutal court case and legal pushback) did women officially get the vote in Maryland.

The South

Arkansas

Arkansas was a bit ahead of the curve when it came to suffrage, being twelfth of the first dozen states to ratify it, which they did on July 28, 1919. But the right to suffrage didn’t come easy, with not only men, but also women trying to stand in the way of it becoming law. Arkansas even had their own Phyllis Schlaftly-type in Matilda Fulton. Married to a state senator, she ran the family plantation whle her husband was in DC, yet pushed the idea of seperate spheres for men and women, where women belonged in the home, while the men took care of everything else.

Nevertheless,while no organized women’s suffrage organization ever came together in Arkansas, in 1888 three women started a small magazine called “The Woman’s Chronicle” which quickly became the central literature for women’s suffrage in Arkansas and its surrounding Southern states. For the next decade, women began gathering in loosely formed women’s suffrage society meetings, and by 1911 they began to lobby their state representatives, hard. By 1917, women had won the right to vote in Arkansas primaries, and just a few years later, had gained the right to vote in all state and federal elections.

Florida

Almost all women’s suffrage groups in Florida only supported the white woman’s right to vote, so, African American women were frequently excluded from the suffrage organizations. Florida did not hold a vote on the 19th amendment because many in the state were against women’s suffrage. In Florida, there is still a law that unmarried women cannot cohabitate with opposite sex. The Sunshine state didn’t ratify until May 13, 1969.

Georgia

The National American Woman Suffrage Association’s 1895 convention was held in Atlanta which was a big step to recruit southern white women while black women were not granted membership. African American suffragettes like Adella Hunt Logan, Mary McCurdy, and Janie Porter Barrett were instrumental in advancing women’s suffrage on a national scale despite white suffragettes pushing for “literacy tests” for voting that targeted to suppress African Americans from voting. While women across the county were able to vote in the 1920 presidential election, Georgia women were not able to cast their ballots because Georgia cited a rule that required voters to register 6 months before an election so women in Georgia were unable to vote on a national scale until 1922. Including the heartbeat bill that was passed in Georgia, there are still antiquated laws in Georgia like the fact that women can be fired for a period leak.Georgia ratified February 20, 1970.

Louisiana

In 1896, New Orleanian Kate Gordon listened to a woman from Colorado speak at her church on the subject of suffrage. It inspired Gordon to found a club called the “ERA” club–“Equal Rights for All.” Unfortunately, however, Gordon turned out to be rabid racist with little concern about actually obtaining equal rights for all. “[G]iving the right of the ballot to the educated, intelligent white women of the South…will eliminate the question of the negro vote in politics…” she said, essentially arguing that if white women could vote, it would diminish the influence of black voters in elections. Members of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association were not comfortable with this approach, and Gordon, a Trumpian-style divisive and petty leader, decided to form her own group in 1913, the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference (SSWSC). Her group would keep their focus on suffrage as a State’s rights, rather than federal, issue. But, sick of Gordon’s leadership, The SSWSC spun off another group, Woman Suffrage Party of Louisiana. The WSP worked hard to win suffrage at the federal level and denounced Gordon’s racism. By 1919,35 states had ratified the federal amendment, needing just one more state to get the amendment passed. What did Gordon do? Went out and rallied AGAINST passage in both Louisiana and Mississippi. When Lousianna voted against ratification, she ran to Tennessee in a last-ditch effort to stop it from being passed there. But alas, Tennessee voted to ratify, and it was all over. Women had won the right to vote. Gordon and her sister were not happy. “I am in the position of a woman who has worked for suffrage all her life, and now that it has come about I do not want it,” her sister said.

North Carolina

Women’s suffrage had a lot of support in North Carolina. But many of the state representatives could not agree on whether or not to recognize women’s suffrage rights and after Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify, they postponed ratifying till the 70s. Only recently did North Carolina reform their sexist laws about assault like the idea that sexual consent cannot be withdrawn during sex and more safety protections for children. North Caroline ratified May 6, 1971.

South Carolina

On January 28, 1920, South Carolina voted to reject the 19th Amendment. They officially ratified the 19th Amendment almost 50 years later ratified July 1, 1969. In 2015, South Carolina was one of the 4 states without equal-pay protections for women.

Virginia

On February 12, 1920, Virginia voted against ratifying the 19th Amendment. Virginia showed its support for women’s suffrage by officially ratifying the 19th Amendment February 21, 1952. While there are not a lot of explicitly sexist laws in Virginia, there are still many antiquated racist laws in Virginia.

D.C.*

Organizations like the National Woman’s Party had a national headquarters in DC where women would gather and plan demonstrations in front of the White House or Capitol Building where politicians and government officials could see. Since Washington, D.C. is a federal district, it could not participate in the ratification process so women in the District of Columbia were not able to vote in 1920, but neither were men. It took another constitutional amendment, the 23rd Amendment ratified in 1961, for District of Columbia residents to win the right to vote for President and Vice President. The country ratified March 22, 1920)

West Virginia

On March 10, 1920, West Virginia voted to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. And while this is, surprisingly, progressive for West Virginia, this state has still never had a female governor.

Kentucky

Kentucky was at the forefront of the movement for women’s suffrage, not just in the South but in the nation, ratifying January 6, 1920. While white women won the right to vote on tax and education issues in rural areas of Kentucky in 1838, ten years before the Seneca Falls Convention, making Kentucky the first place anywhere in the country where women could participate in the electoral process since New Jersey revoked women’s access to the ballot in 1807. The early suffrage efforts in Kentucky included advocacy for equal rights for both African Americans and women, but by the 20th century, the groups were segregated with white suffragettes pushing for “literacy tests” for voting. Recently, Kentucky almost passed the heartbeat bill and has lots of restrictions for abortions even though it used to be pretty progressive for abortions.

Tennessee

The state senate voted to ratify, but in the state house of representatives, the vote resulted in a tie and, acting on advice from his mother Phoebe, a young man named Harry Burn cast the tie-breaking vote to ratify the amendment. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment. However, like Kentucky, Tennessee has a lot of work to do since the heartbeat bill was almost passed in 2019.

Alabama

Like many southern states, most of the suffrage groups in Alabama only advocated for white women’s suffrage. Despite the many organizations pushing for Alabama to ratify the 19th Amendment, the state rejected the amendment after the Women’s Anti-Ratification League, who thought Alabama women should be more concerned about raising families, emphasized their opposition to the amendment. In Alabama, child marriage is still legal, the heartbeat bill was almost passed and only in 1986 was marital rape deemed illegal. Alabama ratified on September 8, 1953.

Texas

Surprisingly, Texas was the first southern state to ratify the 19th amendment on June 28, 1919. The Texas Suffrage movement waxed and waned for many years in the late 1800s. White Texan women’s suffrage mostly involved the campaign for prohibition and temperance with the Texas Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Mexican suffragist, Jovita Idar wrote pro-suffrage articles for her family’s Spanish-language newspaper, La Cronica in 1919. Her work called on working women to join the fight for the vote. While suffrage and anti-suffrage activism increased in the 1910s, Texas women did win the right to vote in primary elections in 1918, however, legislation was defeated when put to the male voters still barred from voting in that general election.

The Midwest

Ohio

Ohio ratified the 19th amendment on June 16, 1919. The fight for the right to vote was largely led by Ohio Womans’ Suffrage Association President Harriet Taylor Upton. The Ohio Women’s Convention was held in 1850 and was the first statewide women’s rights convention; it was attended by about 500 people, many of them anti-slavery activists. The next year, at the same event, Sojourner Truth gave her famous “Ain’t I A Woman” speech that highlighted the difference in treatment white women received from Black women.

Michigan

Michigan ratified the 19th amendment on June 10, 1919. Women in Michigan had been petitioning state legislature for a chance to be on the ballot since 1855. The movement was largely led by Dr. Anna Howard, the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association Shaw and the first woman ordained as a Methodist minister. When Michigan passed a state constitutional amendment, women gained the right to vote in 1918, two years ahead of the federal law change.

Illinois

Illinois hoped to be the first state to ratify the 19th amendment, and it almost was. In the legislators’ haste to be the first, they made a mistake in the forms and had to scramble to fix it. Illinois became the seventh state to ratify the amendment on June 17, 1919. Before then, Illinois women had limited voting rights—only presidential and municipal elections—in 1913. Iconic suffragist, journalist, and anti-lynching advocate Ida B. Wells founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago the same year to educate Black women about the political process—her work played a big role in the election of Chicago’s first Black alderman in 1914.

Indiana

Indiana was a bit later to the ratification game than other states, ratifying the 19th amendment on January 16, 1920. Susan B. Anthony visited many times to advocate amending the state constitution and, in 1897, she told the General Assembly “I want the politicians of Indiana to see that there are women as well as men in this State, and they will never see it until they give them the right to vote. Make the brain under the bonnet count for as much as the brain under the hat.”

Since Black women were largely excluded from suffrage work white women were doing, they created their own associations, one of which met at Madam C. J. Walker’s house—the country’s first Black woman millionaire and subject of the Netflix mini-series Self Made starring Octavia Spencer.

Wisconsin

White women in Wisconsin were able to vote as early as 1884 thanks to the lobbying of activists, although the voting was in limited capacities. White women could vote in elections that related to school issues starting in 1884. The law was rescinded by the state court three years later, but restored by 1901. One major player in Wisconsin women’s right to vote was Jessie J. Hooper, leader of the Wisconsin Woman Suffrage Association. She was one of the thousand activists who marched on the 1916 Republican National Convention to get the Republican Party to support the suffrage amendment. Wisconsin was one of the first states to ratify the 19th amendment on June 10, 1919.

Minnesota

Although Minnesota white women could vote in school board elections starting in 1875, suffragists like Sarah Berger Stearns and Harriet Bishop formed the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association in 1881 and got hundreds of women to join. The MWSA president, Dr. Martha Ripley, fought for women’s rights in healthcare and employment as well as voting. As Minnesota’s largest immigrant group at the time, the Scandinavian Woman Suffrage Association combined its work for suffrage with celebrations of heritage. By 1919, Minnesota white women won the right to vote in presidential elections and had a suffrage organization membership count greater than 30,000. Minnesota ratified the 19th amendment on September 8, 1919.

North Dakota

White women in North Dakota almost had the right to vote decades before the rest of the country but were shot down multiple times. Before the territory was made into two states, the “Dakota Territory”—comprising what is now North and South Dakota—was considered a territory. North and South Dakotas were made states in 1889. Legislation that would have given white women full suffrage rights failed by one vote in 1875 in the state legislature. In 1885, a similar bill passed through the legislature but was vetoed by the “territorial” governor. Again in 1893, a bill giving white women full voting rights passed in the legislature and had plans to be signed by the governor until the speaker of the state house refused to sign it. The bill was then “lost.” In 1913, a women’s suffrage bill passed the legislature but was then given to the state’s male voters, where it was defeated.

One big player in ND’s fight for suffrage was Linda Slaughter who helped to establish the town of Bismarck and was an advocate for both women and indigenous people. North Dakota ratified the 19th amendment on December 1, 1919.

Oklahoma

Temperance played a major role in most southern women’s suffrage movements. In Oklahoma, the movement started in 1890 by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. By 1904 the Woman Suffrage Association of Oklahoma and Indian Territory was founded and included politicians with the hopes of pushing the movement forward. The movement’s progression was delayed because Oklahoma wasn’t granted statehood until 1907. February 28, 1920, Oklahoma ratified the 19th amendment. The victory was followed by the Oklahoma Woman’s Suffrage Association being replaced with the state chapter of League of Women Voters.

South Dakota

South Dakota’s early history of women’s suffrage is the same as North Dakota’s, since the two were once territory until 1889. However, after the two states were created, South Dakota saw three women’s suffrage amendments fail the legislature in 1889, 1895, and 1898. However, SD women had a few powers on their side. Congressman John Pickler—nicknamed “Petticoats Pickler”—was a staunch advocate for women’s suffrage along with his wife Alice.

In SD, activism for women’s suffrage often was grouped in with the fight for prohibition. That was until Mary Shields Pyle, organizer of the South Dakota Universal Franchise League, advised that suffragists separate themselves from the prohibition movement because it was hurting the fight for voting rights. Suffrage amendments were defeated in both 1914 and 1916, although public support was growing. Two years later, white women won full suffrage when the Citizen Amendment was passed—it added a citizenship requirement and removed the word “male” from voting eligibility requirements.

Iowa

Unlike many other states’ approaches to suffrages, Iowa women didn’t think protesting was the best way to win the vote, despite one of the biggest marches taking place there in 1908. Why didn’t they think demonstrating would do anything? “To argue is fatal. The one thing we can do is distribute dignified, indisputable literature that will command the attention of the ‘anti’ because of its saneness and authenticity,” said suffragist Ruth Gallagher in the Muscatine News-Tribune in 1916.

There were multiple failures in trying to send suffrage legislation through the legislature starting in 1870, with a few small victories along the way as well. In one such victory, Iowa white women won limited voting rights in 1894, gaining the ability to vote only on ballots pertaining to bond or tax. After multiple failures to pass women’s suffrage through to law, in 1916, a measure was put on the ballot to be decided by male voters, where it was voted down. Iowa white women gained full voting rights when Iowa ratified the 19th amendment on July 2, 1919.

Kansas

Kansas did not play around when it came to women’s right to vote. In 1867, the state was the first in the U.S. to hold a statewide popular referendum on women’s suffrage; officially recognized a woman’s right to vote in local elections in 1889, and in 1912 (eight years before the 19th Amendment was ratified) Kansas recognized the right of women to vote. Championing these victories were Kansas suffragists such as Mamie Dillard and Carrie Langston (mother of Langston Hughes), who concentrated efforts across both white and Black communities to create a movement that was both intersectional and cohesive. The state officially ratified the 19th Amendment on June 16, 1919.

Missouri

Missouri women began forming organizations for the suffrage movement in 1867. Before the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, suffragists in Missouri tried to petition for the state to add a constitutional amendment enfranchising women eighteen times. Of those eighteen times, only eight of them ever made it to the state legislature, where it was voted against each time. Francis and Virginia Minor were Missourians who spoke at the St. Louis National Woman Suffrage Convention in 1869 where they introduced the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment protected women’s right to vote, and this strategy gained traction and became known as the “new departure.” Virginia Minor was arrested for attempting to register to vote. The family sued and it ended up in the Supreme Court, where they ruled against Virginia Minor’s right to vote. Despite the Supreme Court ruling, Virginia Minor remained active in the fight for suffrage until her death in 1894. Thanks to her activism, Missouri was one of the original 36 states to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the right to vote and ratified it on June 4, 1919.

Nebraska

The fight for women’s suffrage in the state of Nebraska started as early as 1855 when a suffragist Amelia Bloomer spoke to an audience at Omaha’s Douglas House. The movement gained more traction when several groups across the state formed the Nebraska Women’s Suffrage Association in 1881. In the 1880s, Erasmus Correll, a member of the House of Representatives, introduced a bill that would enfranchise women, showing the importance of males showing up. In 1917, the movement got a victory when women were given the municipal vote in the state. But unfortunately, an anti-suffrage group produced a referendum petition which sought an annulment of the new statute that allowed women to vote. The petition was eventually declared fraudulent after a court battle, which unfortunately came too late to achieve the statute’s original purpose, but did boost support for the women’s suffrage movement. Nebraska was the fourteenth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment and did so on August 2, 1919.

The Southwest

New Mexico

New Mexico was considered to be “unusual among western states in not giving women suffrage.” While New Mexico became a territory in 1850 and a state in 1912, The slow-paced ratification state was the 36th to do so. At the forefront of the New Mexico suffrage movement was Julia Duncan Brown. After the victory, Brown would be quoted, “We knew exactly what we wanted and we got it…”

The West

Washington

Washington State has had some ups and downs when it came to the Suffrage Movement. It all started in 1854, Arthur A. Denny, one of the white colonial settlers who “founded” Seattle, Washington (known as occupied Coast Salish, Duwamish, Suquamish land) proposed legislation for women’s right to vote. He proposed “to allow all white females over the age of 18 years to vote” but was denied by one single vote. Mildred Andrews in “Washington Women as Path Breaker”, she writes “Historian Edmund Meany speculated that the bill might have passed if Indian wives of white men had been included. At least one of the naysayers was married to a Native American woman.”

The Washington Territory Woman Suffrage Association was founded in 1871 in Olympia, which soon after a territorial legislature gave women the vote in 1883. Sadly, in 1887, women lost their right to vote when the Territorial Supreme Court ruled that Congress did not intend to give territories the power to enfranchise women. One of the main reasons that women voting rights were rebuked, was because of state liquor lobbyists and owners. They feared that sales of liquor would be more difficult with their votes, hence they fought hard to remove their voting rights.

In 1908, the Washington Equal Suffrage Association published the Washington Women’s CookBook. The book contained recipes, housewifery, beauty secrets, and mountaineering with pro-suffrage quotations from Abraham Lincoln to Susan B. Anthony. This book was meant to win the support of male voters putting domesticity as the priority, argungu voting would not deter women from their “duties”. The cookbooks title pages read “Give us the vote and we will cook, the better for a wide outlook.” The book was sold throughout the state and during Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (A-Y-P) Exposition, which is key for putting women’s voting rights on the ballot. In November of 1910, the amendment to the state constitution allowed women, making the fifth state to give women the right to vote Right before the 19th Amendment to the US. The Constitution extended the vote to all the nation’s women.

Oregon

Oregon’s Suffrage history spans for 42 years. Through the successful tour of the Pacific Northwest in 1871 with Susan B. Anthony, the formation of the Oregon Woman Suffrage Association founded by Abigail Scott Duniway in 1873. Many suffragists participated alongside Susan B. Anthony to illegally cast votes during a November election. Oregon Women voting rights were only heeded by school elections, but they were searching for full citizenship, with full voting rights. Duniway created the New Northwest Newspaper in 1871 that held news items, poetry, advice, and opinion pieces to promote economic and social rights for women, as well as the right to vote. On November 5, 1912, women were allowed to vote within the state due to citizenship but many Native women and men were unable to claim U.S. citizenship and the vote until the federal Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. And first-generation Asian immigrants, male or female could not obtain citizenship and could not vote at all. Abigail Scott Duniway was the author and signed Oregon Equal Suffrage Proclamation Duniway became the first woman to vote in Oregon when she cast her ballot at the polls in 1914.

California

Starting in the 19th century, California women’s right to vote passed in the state through Proposition 4 on October 10, 1911. There were multiple attempts to pass this legislation before it was officially ratified. In 1868, orators Laura de Force Gordon and Anna Dickinson gave a series of lectures advocating for women’s suffrage. and in 1870 Laura de Force Gordon founded the California Woman Suffrage Society. The Defeat of Amendment 6 in 1896, which was to grant women’s right to vote was due to when two newspapers, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times, did not endorse the movement. Black women and Latina women played a key role in the women’s suffrage movement. The Fannie Jackson Coppin Club was an important club for African American women in Alameda County who were active in the suffrage movement, with Lydia Flood Jackson and Hettie B. Tilghman as leaders. One of the major organizers of the suffrage campaign in southern California was Maria de Lopez. Maria Guadalupe Evangelina Lopez, president of the College Equal Suffrage League, served as a Spanish translator for the movement. She also was the first woman to give a speech in Spanish in support of women’s suffrage. On November 8, 1911, Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee became the first Chinese woman to register to vote in the United States.

Colorado

Suffragists in Colorado knew the power of the written word. “Newspapers were a big part of [passing women’s suffrage],” says Jillian Allison, director of the Center for Colorado Women’s History. “Most of the women who were involved in our organizations were also writers in some capacity, so they were able to persuade people in that way.” Caroline Nichols Churchill was the editor of Queen Bee, a feminist Colorado publication. Elizabeth Ensley, an African American suffragist in Denver wrote for, The Women’s Era, a publication of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. Ellis Meredith, referred to then as “the Susan B. Anthony of Colorado,” was a reporter for the Rocky Mountain News. She became corresponding secretary for the Colorado Nonpartisan Equal Suffrage Association and often communicated with Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt through letters. Thanks to the work and writing of these key figures as well as other dedicated suffragists, Colorado became the first state to enact women’s suffrage by popular referendum.

Montana

Women’s right to vote was officially passed on On November 3, 1914, to white women. Jeannette Rankin was a prominent player in the Montana suffrage movement. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union mobilized its 1,500 members to engage in a neighbor-to-neighbor campaign. And local groups, like the Missoula Teachers’ Suffrage Committee, published and distributed 30,000 copies of their leaflet “Women Teachers of Montana Should Have the Vote.” Through the combined efforts of these groups, they pushed for women’s voting rights into reality.

Idaho

On February 11, 1920, Idaho ratified the 19th Amendment. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union played an important role in the women’s suffrage movement. Through women’s participation in WCTU, suffragettes were born. But tensions arose when the WCTU suffragists pushed prohibition of alcohol. The President of the Idaho Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Henrietta Skelton, advocated for this. But Oregon suffragist Abigail Scott Duniway gave a speech and demanded to separate women’s voting rights from prohibition. So women would have a stronger chance of winning. These two positions were a pivotal point in Idaho’s suffrage history.

Nevada

Nevada’s timeline for women voting rights dates back as far as 1869. It took a turn around of five times for the Legislature to pass women voting rights. Lawyer Anne Martin became active in the Nevada Equal Franchise Society, founded in Reno, and in early 1912 she was named its president with Bird Wilson as vice president. They held lectures, tours and passed around 10,000 copies of suffrage news pamphlets that helped progress the passage of women’s voting rights in Nevada. It also enlightened many women who previously had very little idea what their rights were under the law. On February 7, 1920, Nevada voted to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Wyoming

While on January 27, 1920, Wyoming voted to ratify the 19th Amendment, Wyoming was the first territory or state in our nation’s history to grant women the right to vote with the Wyoming Suffrage Act of 1869. Two women had recently delivered speeches in Cheyenne in support of women suffrage: Anna Dickinson at the courthouse in the fall, and Redelia Bates to new legislators in November. But it was local party politics and men who were pushing for women voting rights. They were willing to go even further to get Wyoming good publicity that would draw more settlers to the new territory. The Democratic party hoped that granting women voting rights would give way for their continuous support of the party. Governor John Allen Campbell was the first territorial governor to sign a woman’s suffrage bill into law.

Utah

Utah was the first territory to cast ballots on February 12, 1870, following in Wyoming’s steps for women to have the right to vote. The idea of women’s suffrage in Utah was linked with the Mormon practice of polygamy right from the start. However, many Americans considered polygamy morally wrong and oppressive to women. Having women the right to vote, made hope for those who were against polygamy to have it be voted as illgeal. But because that did not happen, Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887. This legislation took away the voting rights of all Utah women, whether they were Mormon or not, polygamous or monogamous, married or single. Utah women had been voters for seventeen years, so many of them were outraged when Congress took those rights away. Angered, women in Utah created the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah. In 1890, LDS Church president Wilford Woodruff officially ended the practice of polygamy. Which then resulted in Congress passing the 1894 Enabling Act, inviting Utah to again apply to enter the Union as a state, since it was not considered a state due to polygamy. In 1896, Congress accepted Utah’s constitution and granted Utah statehood and Utah women were given back the vote

Arizona

Suffragists Josephine Hughes, Frances Munds, Mary J. R. West, and Mable Ann Hakes pressed for women to have the right to vote as Arizona was to be ratified as a state. But statehood and suffrage were denied by President Benjamin Harrison. Which led to the foundation of the Arizona Suffrage Association with future senator Frances Willard Munds as secretary. Again in 1903 and in 1910, while a Suffrage Bill was passed by both houses of the Arizona Legislature, Governor Alexander Brodie vetoed the bill citing constitutional and statehood issues. Eventually, with Arizona becoming a state in 1912, women’s voting rights became ratified on February 12, 1920, eight years later.

By Evi Arthur (Midwest)

Georgia Dodd (South)

Riley Mayes (Northest)

Bry’onna Mention (Southwest)

Natalie Valencia (West)

with additional reporting by Br’yonna Mention, Debbie Stoller, and Francesca Volpe

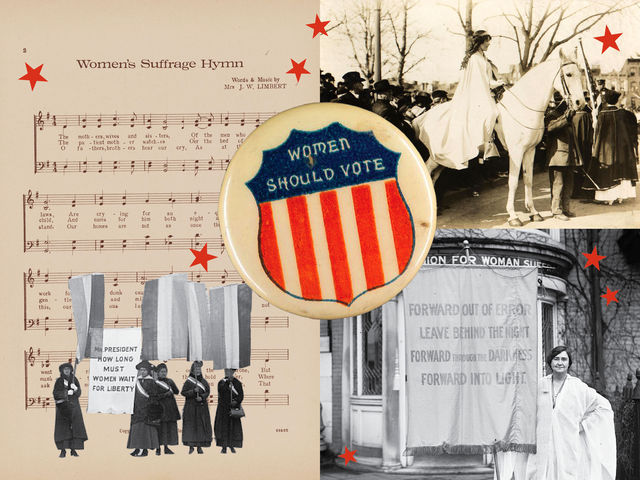

Collage by Aeva Karlsrud

photo credit: Top Left: Library of Congress; Top Right: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection; Bottom Right: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, photograph by Harris and Ewing; Cutouts: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, photograph by Harris and Ewing; Button: Museum of the City of New York, ca. 1890 -1920 button

More from BUST

How Racism Split The Suffrage Movement

Suffragette City: Meet The Young Women Behind The Suffrage Movement In The U.S.

These Suffragette Cats Are EVERYTHING