“Do you think life is worth living?” the young man asked, somewhat menacingly. The year was 1889, and the man had been hounding 23-year-old journalist Nellie Bly for the past few days as they traveled on a ship from Singapore to Hong Kong. Now, on a stormy evening, he had her alone on deck, and his tone had become threatening. “Yes, life is very sweet,” Bly answered, but the man continued talking wildly, sitting at the foot of her deck chair. “I could take you in my arms and jump overboard, and before they would know it we would be at rest…. Death by drowning is a peaceful slumber, a quiet drifting away.” Terrified, Bly tried to keep him talking—“I felt the first move might result in my burial beneath the angry sea,” she later recalled. Just then, a chief officer came on deck. When he came close enough to tease the man about his wooing technique, Bly had her chance. “Come!” she shouted, breaking away and fleeing below deck, where she was able to explain what had really been going on. After that, she recalled, “I was careful not to spend one moment alone and unprotected on deck.”

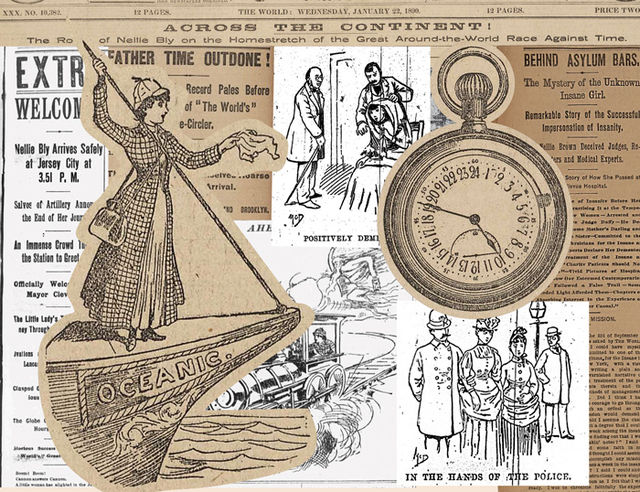

The encounter was perhaps the most dangerous moment in a career filled with risk-taking and adventure. When Bly left New York in November 1889 to circumnavigate the globe, in an effort to break the fictional Phileas Fogg’s record of 80 days, she was already a star reporter. She had written about the working lives of factory girls in Pittsburgh, gone toe to toe with a crooked lobbyist in Albany, New York, and spent 10 harrowing days posing as an inmate at the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum. Written in a chatty, compulsively readable style, her exploits reached thousands of Americans, first in The Pittsburgh Dispatch, then The New York World. When she returned home in 72 days, six hours, and 11 minutes, her fame reached new heights. Her name and likeness were on cigarette trading cards—there was even a Nellie Bly board game.

Born Elizabeth Jane Cochran on May 5, 1864, in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania, a small town outside of Pittsburgh, Bly’s life was a rollercoaster of riches and rags that wouldn’t have been entirely out of place in one of the era’s “penny dreadful” novels. Her father, Judge Michael Cochran, was a local politician and real estate owner; the town had originally been called Pitts’ Mill, but after Cochran’s first term as associate justice, its name was changed to honor him. Both of Elizabeth Jane’s parents had been widowed before marrying each other, and she grew up with 10 half-siblings in addition to her four full brothers and sisters. Rather than the gray or brown dresses that most girls wore, Mary Jane Cochran chose pink dresses for her first daughter, earning her the nickname of Pink, which stuck for the rest of her life.

Round The World With Nellie Bly, a McLoughlin Bros. Board Game, c. 1890. The Liman Collection

Round The World With Nellie Bly, a McLoughlin Bros. Board Game, c. 1890. The Liman Collection

Her father’s unexpected death in 1870 dramatically changed six-year-old Pink’s life. Judge Cochran had failed to write a will, and Pink’s oldest half-brother challenged his stepmother in court over the judge’s assets, leaving Pink’s family in much reduced circumstances. Then, three years later, Mary Jane Cochran married for a third time. Her new husband, Jack Ford, was mean when sober and abusive when drunk, which he was much of the time. In 1878, Mary Jane Cochran Ford took the drastic step of divorce, charging her husband with “cruel and barbarous treatment.” Fourteen-year-old Pink testified at the proceeding that she had heard Ford call her mother a whore and a bitch, and that she twice had seen him try to choke her.

The divorce was granted in 1879. Pink was 15. To help support her adored mother, she enrolled in the State Normal School in nearby Indiana, Pennsylvania (“normal school” was 19th century nomenclature for “teacher’s college”), intending to make money in one of the few ways a woman could at the time—even though she’d never been a good student (a schoolmate later recalled her as more conspicuous for “riotous conduct than profound scholarship”). Away from home for the first time, she added a sophisticated silent-e to her last name. Forced by money troubles to leave school before the end of her first term, the name change would be the most lasting effect of her attempt at higher education. She would be Pink Cochrane to friends and family for the rest of her days. Back home and at loose ends, Pink and her family moved to an as-yet unincorporated section of Pittsburgh in 1880. Biographer Brooke Kroeger notes that “nothing is known for certain” about Pink’s life between the ages of 16 and 20, though there are “indications she tried her hand” at several traditionally female occupations: tutoring, childcare, housekeeping.

One of the ways Pink entertained herself during these years was by reading “Quiet Observations,” a column in The Pittsburgh Dispatch written by Erasmus Wilson, an irascible male chauvinist who nevertheless later became Nellie Bly’s mentor. In 1885, a man who signed himself “Anxious Father” wrote to Wilson, worried about his five unmarried daughters who had no skills with which to support themselves. Wilson provided no advice, but longed for the good old days when girls learned how to keep house for the men who supported them. He facetiously suggested the day might come “a few thousand years hence” when surplus girl babies would best be killed. When Anxious Father understandably wrote back to protest, Wilson noted, “There is no greater abnormity than a woman in breeches, unless it is a man in petticoats.”

Nellie Bly, c. 1890. Photo: Meyers/Library of Congress

Nellie Bly, c. 1890. Photo: Meyers/Library of Congress

The exchange ignited a storm of reader mail—including a letter from then-20-year-old Pink Cochrane, signed “Lonely Orphan Girl.” The letter caught the eye of The Dispatch’s managing editor, George Madden, and though he didn’t publish the letter, Madden thought the writer had the makings of a reporter. She wasn’t “much for style,” but there was something about the direct way she expressed herself “regardless of paragraphs or punctuation.” But who was she? Lonely Orphan Girl didn’t put a return address on her letter. At Wilson’s suggestion, the editorial page of the January 17, 1885, the Pittsburgh Dispatch carried the following notice: “If the writer of the communication signed ‘Lonely Orphan Girl’ will send her name and address to this office, merely as a guarantee of good faith, she will confer a favor and receive the information she desires.”

The following day, Pink Cochrane climbed the four flights of stairs to The Dispatch’s newsroom. To her surprise, Erasmus Wilson was “a great big good-natured fellow who wouldn’t even kill the nasty roaches that crawled over his desk,” she recalled. Madden paid her to write a new version of the letter, which he personally edited. “The Girl Puzzle” was published on January 25, 1885, under a slightly edited nom-de-plume: “Orphan Girl.”

“What shall we do with our girls?” asked Orphan Girl. Not the exceptional ones, but those “without talent, without beauty, without money.” The answer was, she thought, to treat “our girls” like boys: Train them for jobs that weren’t those traditionally held by women, as office messengers, for example, or traveling merchants, and pay them the same wages. “We have in mind an incident that happened in your city. A girl was engaged to fill a position that had always been occupied by men, who, for the same, received $2 a day. Her employer stated that he never had anyone in the same position that was as accurate, speedy, and gave the same satisfaction; however, as she was ‘just a girl’ he gave her $5 a week. Some call this equality,” she wryly concluded.

Nellie Bly, 1890. Photo: Myers/Library of Congress

Nellie Bly, 1890. Photo: Myers/Library of Congress

Pink followed up with an article headlined “Mad Marriages,” in which she called for the reformation of marriage laws as the best preventative for divorce. “Let the young girl know that her intended is cross, surly, uncouth,” she wrote, perhaps thinking of her mother’s ill-starred third marriage, “let the young man know that his affianced is anything that is directly opposite to an angel. Tell them all their faults, then if they marry, so be it; they cannot say, ‘I did not know.’” The column, which appeared in The Dispatch on February 1, 1885, was bylined “Nellie Bly.”

“Pink Cochrane” was a great name, but almost every woman journalist writing in the 19th century used a pseudonym. Writing for a newspaper wasn’t considered “ladylike,” and a fake name provided a veil of respectability between writer and public. As “Bessie Bramble,” The Dispatch’s lone female columnist, Elizabeth Wilkinson Wade, tackled subjects including the status of working women, abusive husbands, and divorce. Managing editor Madden wanted his newest hire to have a pen name, too, something “neat and catchy,” so he asked his newsroom for suggestions. “Nelly Bly” was the title of an 1850 song by Stephen Foster, a white man who wrote minstrel songs. The story goes that Madden misspelled “Nelly” as “Nellie” in his rush to print, but it should be noted that Nellie Bly was also the name of a popular trotting horse at New York racetracks in 1880. Whether the newsman who shouted out the name was thinking of song or horse, the name fit the bill.

The newly-dubbed Nellie Bly wrote an eight-part series about Pittsburgh’s female factory workers, then found herself assigned to a more traditional woman reporter’s beat: gardening, fashion, and music. She spent several months reporting from Mexico about the country’s social customs and politics (she brought her mother along as chaperone), but cut her visit short when authorities objected to a story about government suppression of the press. Back home, she was put on the culture desk.

“He shot down her proposal to report on the immigrant experience by traveling from Europe to the United States in steerage, and instead assigned her to report on the conditions at the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum—from the perspective of an inmate.”

The situation was untenable for an ambitious young reporter. Bly left The Dispatch and moved to New York in May 1887. There, she ran into a wall of resistance. “We have more women now than we want,” she remembered was the combined response to her request for work at the city’s newspapers. “Women are no good, anyway.” She used the situation to her advantage, interviewing “the newspaper gods of Gotham” regarding their feelings about women reporters—in at least one case, by posing as a job applicant—for an article published in The Pittsburgh Dispatch.

The article didn’t result in any job offers, but Bly talked her way into a second meeting with one of her interviewees, the managing editor of The New York World, Colonel John Cockerill. He shot down her proposal to report on the immigrant experience by traveling from Europe to the United States in steerage, and instead assigned her to report on the conditions at the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum—from the perspective of an inmate. She had one question for him: How would they get her out, assuming that she was able to feign insanity well enough to get in? “I do not know,” was the not particularly soothing answer, “but we will get you out….”

Bly practiced what she hoped was a vacant stare, then checked into the Temporary Home for Females, a boarding house on Second Avenue, under the name “Nellie Brown.” She paid for a night’s stay, then proceeded to “act crazy.” She said she was afraid of the other women in the house, then sat up all night. In the morning, she complained about her lost trunks, when she had checked in without luggage. It was a surprisingly successful ruse. Taken to the police court, she raised a ruckus about the missing trunks. The judge sent her to Bellevue. After a brief interview in which Bly claimed to be from Cuba and denied being “a woman of the town” (a sex worker), the admitting physician proclaimed her “positively demented” and “a hopeless case.” She was sent to the asylum.

Illustration from “Behind Asylum Bars,” published in The World, 1887

Illustration from “Behind Asylum Bars,” published in The World, 1887

Bly wrote that from the moment she “entered the insane ward,” she “made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity.” She “talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be by all except one physician.” Along with the other inmates, she endured filth, cold baths, bad food, forced undressings and druggings, and nurses who were indifferent or cruel—they even beat some inmates, including an elderly woman, and choked another so badly that Bly “plainly saw the marks of their fingers on her throat for the entire day.” Bly also found that, though some of the women were “born silly” or “had delusions” and needed care, others showed no sign of mental illness and seemed to have been imprisoned simply because they were poor—“Don’t you know there are only insane women, or those supposed to be so, sent here?” Bly asked one such woman, who responded, “I knew after I got here that the majority of these women were insane, but then I believed them when they told me this was the place they sent all the poor who applied for aid as I had done.”

Oddly, Bly ran the risk of being outed, not by inmates or doctors who spotted a fake, but by reporters trying to identify the “mystery girl” they had seen at the police court, who, while apparently insane, appeared otherwise healthy and well cared for. A reporter who recognized her in the yard at the Island agreed to keep her secret. After 10 days, The World sent an attorney to release her “to the care of friends.”

“I had looked forward so eagerly to leaving the horrible place, yet when my release came and I knew that God’s sunlight was to be free for me again, there was a certain pain in leaving,” Bly recalled. “For 10 days I had been one of them. Foolishly enough, it seemed intensely selfish to leave them to their sufferings. I felt a Quixotic desire to help them by sympathy and presence. But only for a moment. The bars were down and freedom was sweeter to me than ever. Soon I was crossing the river and nearing New York. Once again I was a free girl after 10 days in the mad-house on Blackwell’s Island.”

Illustration from “Behind Asylum Bars,” published in The World, 1887

Illustration from “Behind Asylum Bars,” published in The World, 1887

The first installment of Bly’s two-part series on her stay in the insane asylum appeared on October 9, 1887, the second a week later. As a result of her exposé, the New York grand jury toured Blackwell’s Island, and the city increased funding to the asylum by some $50,000. The series appeared in book form before the year was out.

Throughout her career, Bly interviewed major figures (Emma Goldman and Susan B. Anthony among them) and wrote human interest stories, but “stunt journalism” was her forte—she was the first and the best of the so-called “girl stunt reporters.” Posing as someone you weren’t in order to get a story was not yet seen as an unethical practice. More traditional journalists sometimes viewed the stunt reporters with scorn, but as historian Jean Marie Lutes points out, Nellie Bly and those who followed her “were the first newspaperwomen to move as a group from the women’s pages to the front page.” In the wake of her success at Blackwell’s Island, Bly pretended to be a maid in order to investigate employment agencies. She acted the role of a country girl new to the big city in order to investigate a man who, it was said, paid the police off with beer so he could attempt to lure naive girls into sex work. She went to Albany, where she posed as the wife of a patent medicine manufacturer to meet with powerful lobbyist Edward R. Phelps. For $1,000, Phelps told her, he could get six assemblymen to change their votes and kill a bill. (As a result of her reporting, Bly testified about the matter before the assembly judiciary committee, though they found no evidence of fraud on behalf of their fellow members.)

Nellie Bly’s biggest stunt is the one for which she is probably best remembered. The idea came to her, she said, on a Sunday night. She needed a vacation; why not take a trip around the world? Better yet, why not have The World pay for it? Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days had been a bestseller upon its American publication in 1873. In the novel, a rich British man, Phileas Fogg, along with his valet, Passepartout, races to circumnavigate the globe in 80 days in order to win a wager. What if she tried to do it faster?

“Nellie Bly’s biggest stunt is the one for which she is probably best remembered. The idea came to her, she said, on a Sunday night. She needed a vacation; why not take a trip around the world?”

Her editor was reluctant to send her, but eventually agreed. Bly would travel unaccompanied. Other than the blue broadcloth dress on her back, she brought a plaid overcoat and a single small bag stuffed with necessities. She once regretted not having a dinner dress with her, but more frequently lamented that she had brought too much gear (this did not stop her from buying a pet monkey in Singapore, however). Someone suggested she bring a revolver, but she refused.

She set sail for Europe on November 14, 1889. Over the next 72 days, she passed through approximately 14 cities, including London, Paris (where she made time for a visit with Mr. and Mrs. Verne), Brindisi, Aden, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Yokohama, sending columns by telegraph whenever she could. Bly’s descriptions of other races and cultures were imbued with white, Western bias, but she was a rapt observer of new places and people.

Illustration from “Nelly Bly’s Ride,” published in the World, 1890

Illustration from “Nelly Bly’s Ride,” published in the World, 1890

Bly reached San Francisco in record-breaking time, only to have her eastbound train delayed by snow on the tracks. Even so, she arrived back in New York three days ahead of her own schedule, on January 25, 1890. Unbeknownst to Bly, a rival publication had sent its own stunt reporter, Elizabeth Bisland, around the world in the opposite direction at the same time Nellie traveled east to west—but Bisland was still at sea when Bly was being welcomed home by a crowd of some 5,000 wellwishers. Bly soon thereafter embarked on a lecture tour, describing her trip around the world to rapt audiences. Her columns were expanded into a book, Around the World in 72 Days. The first edition of 10,000 copies sold out within months of publication. “Here is Nellie Bly,” crowed an 1890 article in Good Housekeeping, “sent around the globe just to see how quickly a woman can do it—that is all! She is an incarnation of the breathless spirit of the age.” Around the same time, a newspaper in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, praised Bly’s “pluck and spirit and self-reliance” in “traveling 25,000 miles without a protector” before concluding: “Every American girl should be proud of her.”

Bly worked as a reporter and writer for the rest of her life, save for a pause after she married an elderly industrialist, Robert Seaman, in 1895. As president of Seaman’s Iron Clad Manufacturing Company, Bly secured 25 patents for various parts and procedures related to the manufacture of milk cans and other items. But despite her success, Iron Clad declared bankruptcy in the wake of an employee’s embezzlement. Widowed and enmeshed in a growing number of lawsuits related to both Iron Clad and her family, Bly went back to work as a journalist in 1912, covering that year’s political conventions. She reported from the front lines of the First World War, took a stand against capital punishment, and attempted to get abandoned babies adopted. She was still busy writing when she died of pneumonia at the too-young age of 57 in 1922. “Nellie Bly seemed born to adventure as the sparks fly upward,” recalled The Boston Globe. Her own words from Ten Days in a Mad House provide the most fitting epitaph: “I said I could and I would. And I did.”

By Lynn Peril

This piece originally appeared in the October/November 2018 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

The Shifters Were The 1920s Girl Gang Robbing Shopgirls Of Their Stockings

Leonora Carrington Is The Groundbreaking Surrealist Artist You’ve Never Heard Of

Gladys Bentley Was The Gender Nonconforming, Lesbian Superstar Of The Harlem Renaissanc