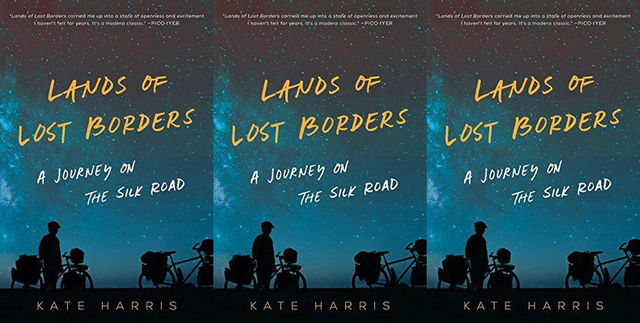

Kate Harris’s memoir of cycling the length of the Silk Road from Turkey to the Himalaya succeeds in becoming a rare thing—a true adventure book by a woman. Not that women going on great adventures and writing about them are rare. But often their tales are wrapped in an additional plot: A breakup. A recovery. A great quest for true, inner self. Which are all important, legitimate stories in themselves, of course. But sometimes it feels that adventure for adventure’s sake is still considered the territory of men. One of the beauties of Lands of Lost Borders lies in how it harkens to a universal, almost childish dream of exploration that transcends gender.

Growing up in small-town Ontario, Harris dreams of being an explorer, falling under the spell of her mother’s childhood book, an illustrated, abridged edition of Marco Polo’s travels on the Silk Road. She devours the literature of discovery, from the first Antarctic expeditions to the travels of Alexandra David-Néel. Harris admires David-Néel for knowing herself and seeking adventure for its own sake—not necessarily being “jolted from a routine, domestic existence by some kind of emotional crisis.” (And Harris’s story lives up to that value.) She envisions becoming an astronaut, obsessing about going to Mars. Her first bike trip cycling part of the Silk Road with a childhood friend seems something like a vacation at first. She comes back to continue a more academic pursuit of discovery—studying the history of science and exploration at Oxford, and then heading to an MIT lab aiming for a doctorate. But the visceral experience of that bike trip sticks with her. The bodily act of crossing borders—both political and geographic—feels more true to her vision of exploration than peering down a microscope. So she and her friend Mel set out again, this time to complete the entire historic Silk Road route.

Through Harris’s imaginative, carefully designed prose, we experience her daily discoveries along with her, from slogging through freezing rain and being warned of terrorists in Turkey, to pedaling into the the hot headwinds of Uzbekistan’s desert, to disguising herself as a Chinese tourist to bike through Tibet’s mountains—where foreigners aren’t allowed without permits and guides.

Alongside those lively descriptions and sometimes-tense moments—What was that sound outside the tent? Should we continue even though our Uzbekistan visas never arrived?—Harris also dives into deeper questions about what it means to be an explorer today, when Earth is well-mapped and surveyed by satellites and most of us travel in relative comfort and ease. The self-awareness she brings to these musings feels refreshing. She clearly sees that her own values of travel reflect the privilege of the country and culture that formed her—but she never loses the contagious idealistic energy that spurred her expedition in the first place.

“ … others have biked higher and farther,” she writes. “and certainly faster, with fewer flat tires and false turns. But exploration, more than anything, is like falling in love: Experience feels singular, unprecedented, and revolutionary, despite the fact that others have been there before.”

More from BUST

“Rage Becomes Her” Validates Women’s Anger—And Tells Us How To Use It For Good

Supergirl Gets A New Origin Story In “Supergirl: Being Super”: BUST Interview

“Throwing Shade” Host Erin Gibson Is “Feminasty” In Her New Book: BUST Interview