When Jane Elliott walked into her classroom in 1968, she introduced an exercise about racism that is still repeated all over the world. We caught up with the ground-breaking educator to discuss teaching kids about race, how there’s no such thing as “white” people, and why Black women are her heroes

In June, Black Lives Matter uprisings against racial violence and police brutality raged from New York to Minneapolis, following the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Riah Milton, and more. In response, the Internet buzzed with viral anti-racist videos and bestselling-book lists about race. Rapper and activist Killer Mike followed suit by giving a homework assignment to white Americans while appearing on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert in the midst of global protests. “Google Jane Elliott and spend one hour” learning from her on YouTube, he advised.

Killer Mike’s directive and the recirculation of Jane Elliott’s past conversations on The Oprah Winfrey Show and Jada Pinkett Smith’s Red Table Talk series reignited interest in her notorious yet controversial “Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes” exercise. In the midst of this momentum, footage featuring Elliott—now a spirited 86-year-old Iowan schoolteacher-turned-diversity trainer and advocate—made the rounds on social media as headlines noted unprecedented white participation in Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

On the upswing of protests worldwide, Elliott declares, “Young people are saying, ‘We cannot go along with this. We cannot call this a democracy and have 15 to 30 percent of our population being treated the way we treat people of color in this country.’”

Elliott’s moment of inspiration came while watching TV on the evening of April 4, 1968. At that time a teacher in Riceville, IA, she had been ironing a teepee she planned to use in a classroom activity about empathy the next day. She rooted her lesson in the message from a prayer often attributed to the Sioux: “Oh great spirit, keep me from ever judging a man until I have walked in his moccasins.” While she prepared for the day ahead, the news tragically turned to the assassination of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., rocking the nation and transforming Elliott’s classroom—and many others for years to come.

When Elliott walked into her third-grade classroom in the aftermath of King’s death, her all-white students from a town of fewer than 1,000 people awaited her with questions about why someone would kill their “Hero of the Month.” In response, she devised a lesson to not just teach them about racism, but also what it feels like to be discriminated against. She has since repeated the exercise with thousands of people. Coverage by BBC, PBS, ABC, and other outlets has catapulted Elliott’s methods into classrooms and workplaces around the world from the United States to Saudi Arabia.

While it has changed a bit over the years, the class basically runs the same way each time, as seen in a 1970 documentary. After discussing racism with her all-white students, she acknowledges that it would be difficult for them to know what it would feel like to be judged by the color of their skin. She then asks if they would like to find out. The students eagerly say “Yes!,” and Elliott’s experiment begins. “I’m the teacher, and I’m blue-eyed. In fact, the blue-eyed people are the better people in this room. They’re smarter than the brown-eyed people,” she proclaims, as a few students giggle. Without cracking a smile, she doubles down, letting the kids know she’s serious. Pointing out one student in the back of the classroom, she asks, “Is your dad brown-eyed?” When the boy answers in the affirmative, she continues. “One day you came to school and you told us that he kicked you. Do you think a blue-eyed father would kick his son?” Another student quickly raises his hand to respond. “My dad’s blue-eyed, he’s never kicked me!” he shouts. The game is on.

Throughout the day, Elliott provides blue-eyed students special privileges, while sidelining brown-eyed students. “Blue-eyed people get five extra minutes of recess, while brown-eyed people have to stay in. Brown-eyed people do not get to use the drinking fountain; you have to use the paper cups. Brown-eyed people are not to play with blue-eyed people in the playground,” she commands, demanding that the brown-eyed kids put on ugly collars “so we can tell from a distance what color your eyes are.”

Not surprisingly, and by design, the brown-eyed students grow frustrated and distressed after being singled out, repeatedly scolded for their mistakes, and segregated from their friends. At the same time, the so-called “superior” blue-eyed students begin mirroring the anti-brown-eyed narrative by mistreating, bossing around, and ignoring their “inferior” schoolmates.

The next day, Elliott changes the rules. “Yesterday I told you that brown-eyed people weren’t as good as blue-eyed people,” she announces. “I lied to you yesterday. The truth is, brown-eyed people are better than blue-eyed people.” The lesson is now played in reverse, but the results are the similar: “superior students” behave more arrogantly and authoritatively towards their lower-status counterparts, while “inferior” students isolate themselves with increased reticence. Even students’ performance on educational tasks is impacted by their position in their classroom power structure, with kids performing worse when they are assigned to the “inferior” group, and performing better when “superior.”

Elliott teaching the “Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes” experiment to her students in 1970

Oftentimes, when she runs this exercise with older students or adults, like on Oprah, someone from the “inferior” group will become so frustrated at how they are being treated, they’ll get up and leave. But Elliott has no patience for this type of “white fragility,” and uses it to illustrate her point. “When you get tired of being treated unfairly because of your eye color, you can just walk out that door!,” she’ll bark, heatedly. “But [people of color] can’t [do that], because there’s no place in this country where they aren’t going to be exposed to racism. They can’t even stay in their own homes and not be exposed to [it] if they turn on the television!”

When I first call Jane Elliott to set up our interview, she gives me a friendly-but-firm note: “When you write this, make sure you don’t introduce me as an anti-racist educator, I prefer to be described as doing pro-human work.” She then clarifies her perspective in our follow-up conversation. “If we teach children to save their lives, then we had best teach children that we are all members of the same race,” she says. “Human beings come in different shades of brown, but we are all shades of brown. There are, however, no people who are white.”

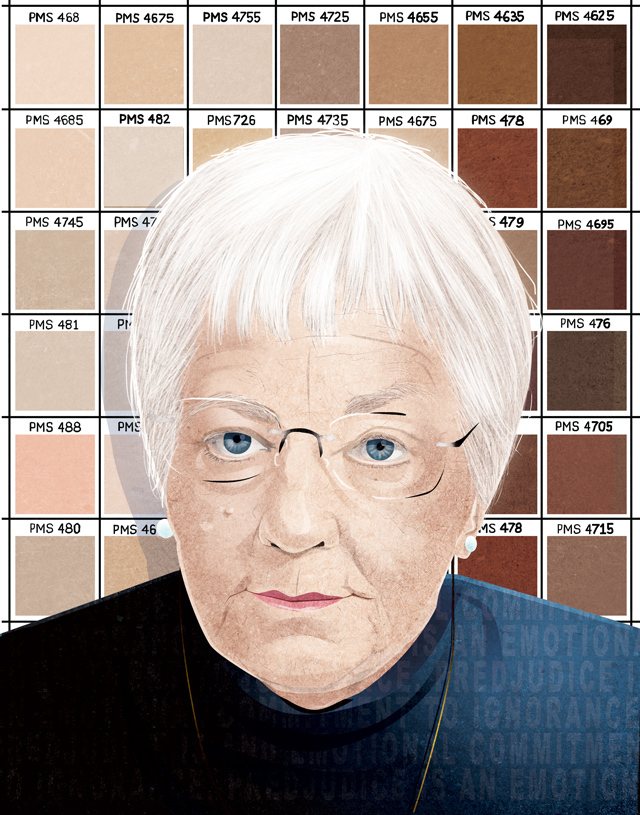

Reflecting on the upsurge of progressive kids’ literature and specifically best-selling books about race in recent months, Elliott suggests that “somebody use the Pantone color wheel in a children’s book,” to educate the next generation about racism and equality. “Put it in a book. And then say to the children, ‘Find the color of the back of your hand or your face on this color wheel. That’s the color of your skin. Your skin is that color because the first modern human beings that evolved on Earth were exposed to great amounts of sunlight, so their bodies produced a lot of melanin. Your great, great, great, great, great, great grandmother was one of those. But as those people moved farther from the equator, they were exposed to less sunlight, so their bodies produced less melanin. That’s [how] people came up with the name white.’” When asked about critics who today, many years after she taught kids about race in school, still disavow using children’s books to introduce youth to concepts like race and systemic power, she sharply retorts, “Do we teach three-year-olds to stay out of the road so they won’t be hit by a car?”

“What’s happening now is the result of Black mothers who refused to give up and refused to believe the ?nonsense that we’ve all been told all our lives.”

Although Elliott is most well-known for her trailblazing solidarity work in racial justice spaces, she is also well-versed on the persistent forces barring equality for all people. While noting the Trump Administration’s threats to reproductive justice, Planned Parenthood, and immigrant rights, she rejects labeling herself as a humanist or feminist, saying, “I see myself as an individual. I won’t join a group. Because then I would have to take on the principles and the policies of that group. And invariably, there would be something where I would say, ‘There is no way I’m going to spout that nonsense.’ I won’t join groups that are calling themselves ‘allies’ of Black people. Because practically all of them have taken on words like ‘unconscious bias’ and ‘conscious bias.’ We would rather talk about [bias] in psychological terms, than say, ‘Here’s what you just said, and here’s what you just did. And here’s why I find it ugly, and I won’t tolerate it.’”

Full of vigor and hope to continue her work, Elliott notes that once the threat of Coronavirus is behind us, she’s keen on reigniting in-person events, especially with her previous co-panelists Angela Davis and Willow Smith. Throughout our conversation, her insistence on centering the leadership and vision of Black women as a path to progress is clear. “I’m not taking credit, nor do I deserve credit, for anything positive that’s happening today,” she says. “The people [who deserve] credit are those Black women who refused to be kept down. My heroes are Black women. Make no mistake about this. They keep on keeping on. And they will overcome. No doubt about it. Because they have to. They have no choice. They have developed coping skills that I will never develop because I don’t have to. What’s happening now is the result of Black mothers who refused to give up and refused to believe the nonsense that we’ve all been told all our lives.”

After inviting me to join her for a “cup of something hot” in Iowa to strategize about remaking the world for the present and future, Elliott chuckles. “Willow [Smith] said to me after I was done with the Red Table thing, ‘Can we go on the road together when this is over? I’d like to go on the road with you.’ I said, ‘When you’re ready to go, give me a call.’ And she laughed, and I laughed.”

By Jamia Wilson

Illustrated by Laura Freeman

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

How Indigenous Women Inspired The Feminist Movement

There Is No Such Thing as Justice for Breonna Taylor

Today Is The 65th Anniversary of Emmett Till’s Lynching—Days After The Shooting of Jacob Blake