Where did early suffragists ever get the idea that women should have the same rights as men? The answer may be in their own backyards—in the egalitarian society created by Native Americans

“One day, a [Native American] woman gave away a fine quality horse.” The audience of women’s rights activists listened attentively as ethnographer Alice Fletcher addressed the first International Council of Women. The scene was Washington, D.C. The date was March 1888. “Will your husband like to have you give the horse away?” Fletcher recalled asking the woman, shocked. The Native woman’s “eyes danced,” Fletcher told the suffragists and, “breaking into a peal of laughter, she hastened to tell the story to the others gathered in her tent, and I became the target of many merry eyes. Laughter and contempt met my explanation of the white man’s hold upon his wife’s property.”

Fletcher had forgotten just for a moment that she was with Native, not white women. No white woman would dare give away her family’s horse. In fact, married white women had no legal right to their own possessions or property in most states, but that was just the tip of the iceberg. Far beyond simply lacking rights, married American women had no legal identity. They couldn’t vote, have guardianship of their own children, or have autonomy over their own bodies. A wife and mother didn’t exist in the eyes of the law; she became one with her husband the moment they were joined in matrimony. In fact, husbands were legally within their rights to beat their wives if they chose. Yet for most women, getting married was the only way to support oneself. Most jobs were closed to them and the few available ones paid half (or less) of the wages that men were paid for the same work. The founding document of America’s women’s movement, the 1848 “Declaration of Sentiments,” summed it up well: “He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.”

Haudenosaunee women grinding corn or dried berries, with infant on cradleboard in background

Haudenosaunee women grinding corn or dried berries, with infant on cradleboard in background

Women’s second-class position in Western society had been in place for centuries. Even in the 1800s, most white people were still guided by the Biblical notion that God made Adam first, then Eve as a helpmate. When she was disobedient in Genesis 3:16, the text stated that Eve and all women after her would be under the authority of men as punishment. “Thy desire shall be to thy husband,” The Bible said, “and he shall rule over thee.”

But the early feminists had to wonder: Was woman’s degraded position truly God-ordained as a punishment for Eve’s sin? Did it develop over time, with women depending upon men’s greater strength and wisdom to survive? If either was true, the oppression of women would be universal, they reasoned. Once the early suffragist-feminists discovered the authority and respect women held in Native American nations, however, they knew beyond a doubt that their subjugation was man-made, and they resolved to fight for a similar world of equality for themselves.

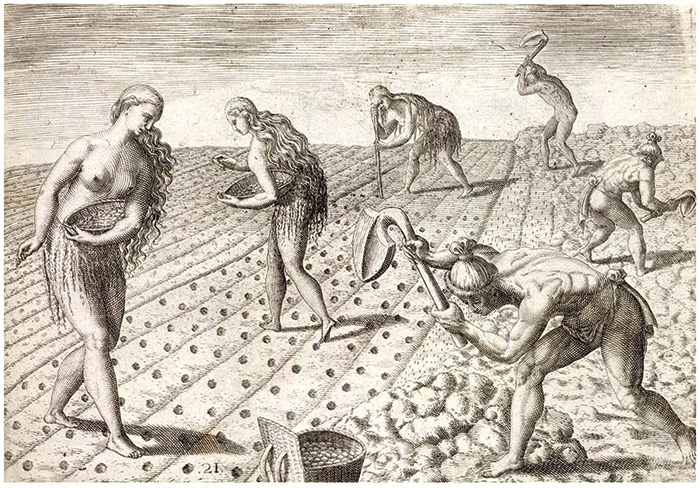

Two of the earliest founders of the U.S. women’s movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage, saw the egalitarian Native model first-hand while growing up in New York, the land base of the Haudenosaunee—a label denoting the five nations of the Iroquois confederacy: the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca—later joined by the Tuscarora. Native women were the agriculturalists of their tribes, and from North to South America they collectively raised corn, beans, and squash. Their responsibility for the survival of the Nation, through the creation of life and the food that sustained life, gave women a position of equality in their society that white women could only dream of.

“In the councils of the Iroquois every adult male or female had a voice upon all questions brought before it,” Stanton reported in The National Bulletin in 1891. “The American aborigines were essentially democratic in their government….The women were the great power among the clan.” Stanton went on to describe how clan mothers had the responsibility for nominating a chief, and could remove that chief if he did not make good decisions. “They did not hesitate, when occasion required,” Stanton recalled, “‘to knock off the horns,’ as it was technically called, from the head of a chief and send him back to the ranks of the warriors.”

Their responsibility for the survival of the Nation, through the creation of life and the food that sustained life, gave women a position of equality in their society that white women could only dream of.

Gage, who was the third member of the National Woman Suffrage Association leadership triumvirate with Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, also wrote about her Haudenosaunee neighbors in her 1893 magnum opus, Woman, Church and State. “Never was justice more perfect; never was civilization higher,” she wrote. “Under their women, the science of government reached the highest form known to the world.”

In particular, Gage was struck by the Native American political power structure. “Division of power between the sexes in this Indian republic was nearly equal,” Gage wrote. “The common interests of the confederacy were arranged in councils, each sex holding one of its own, although the women took the initiative in suggestion, orators of their own sex presenting their views to the council of men.”

Gage not only observed this process, she experienced it as well. Given an honorary adoption into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk Nation in 1893, Gage’s adopted Mohawk sister told her that, “this name would admit me to the Council of Matrons, where a vote would be taken, as to my having a voice in the Chieftainship.” What must this have meant to a woman who went to trial the same year for voting, which was illegal for women to do? Considered for decision-making in her adopted nation, she was arrested in her own state for attempting to do exactly that.

Native American women and men in Florida planting beans or maize

Native American women and men in Florida planting beans or maize

Haudenosaunee women’s authority in “family relations” provided another inspiring model for suffragists. While U.S. women had responsibility for the home, the authority for all decisions ultimately rested with their husbands. Not so with Native women, Gage explained in Woman, Church and State. “In the home, the wife was absolute.”

Although saccharine tribute was paid in the West to motherhood, the harsh reality was that American women, Gage pointed out, had “no legal right or authority over her children.” These laws, Gage wrote, even permitted “the dying father of an unborn child to will it away, and to give any person he pleases to select the right to wait the advent of that child, and when the mother, at the hazard of her own life, has brought it forth, to rob her of it and to do by it as the dead father directed.”

This claim is supported by New York law of the time, which read, “Every father, whether of full age or a minor, of a child likely to be born, or of any living child under the age of 21 years and unmarried, may, by his deed or last will duly executed, dispose of the custody and tuition of such child, during its minority, or for any less time, to any person or persons in possession or remainder.”

“What an anomaly on justice is such a law!” Gage asserted. “‘It is better to be a live dog than a dead lion,’ was a proverb I learned in my childhood—but I have learned a new rendering: ‘It is better to be a dead father than a live mother.’”

“The American aborigines were essentially democratic in their government….The women were the great power among the clan. They did not hesitate, when occasion required ‘to knock off the horns,’ as it was technically called, from the head of a chief and send him back to the ranks of the warriors.”

Issues of paternal rights were totally foreign to the Native world. Haudenosaunee children were (and are) born into their mother’s clan and follow their mother’s line. When Gage tried to explain the concept of an “illegitimate child” to a Haudenosaunee friend, the woman puzzled, “how can any child not be legitimate? You always know who your mother is.” The living arrangements were traditionally based on this matrilineal system. A husband came to live with his wife, her parents, her sisters and their husbands and children in their matrilineal family longhouse. Unmarried brothers lived there, too, until they married and moved to their wives’ longhouses. If any of the mothers died or the couple split up, the children continued to live in the mother’s longhouse. “The children also accompanied the mother, whose right to them was recognized as supreme,” Gage wrote, “if for any cause the Iroquois husband and wife separated.”

Stanton’s study of Native American nations concurred. “From these cases, it appears the children belonged to the mother, not to the father, and that he was not allowed to take them even after the mother’s death,” she wrote. “Such, also, was the usage among the Iroquois and other Northern tribes, and among the village Indians of Mexico.”

Condemned for her public declaration that women should be able to leave loveless or dangerous marriages, Stanton delightedly shared Rev. Ashur Wright’s description of divorce Iroquois-style with the International Council of Women meeting in 1891. “No matter how many children, or whatever goods he might have in the house,” she quoted, the husband “might at any time be ordered to pick up his blanket and budge; and after such an order it would not be healthful for him to attempt to disobey.”

Violence against women was a behavior seldom seen among Indian nations, and when it occurred, it was dealt with severely, generally by banishment or death.

Also not “healthful” to Native American men, was the spousal battery their white counterparts so cavalierly engaged in. In fact, violence against women was a behavior seldom seen among Indian nations, and when it occurred, it was dealt with severely, generally by banishment or death. In fact, white women entered a paradise of personal safety among Native people that they never experienced on their own soil. “It shows the remarkable security of living on an Indian Reservation, that a solitary woman can walk about for miles, at any hour of the day or night, in perfect safety,” Mary Elizabeth Beauchamp, who taught school on the Onondaga Nation, remarked in a letter to the Skaneateles Democrat in 1883.

In the 200 years since the early feminists first came into contact with liberated Native women, very little has changed in terms of their status within their tribes. Iroquois Haudenosaunee women today continue to have the responsibility of nominating, counseling, and keeping in office the male chief who represents their clan in the Grand Council. In the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, Haudenosaunee women have worked alongside men to successfully guard their sovereign political status against persistent attempts to turn them into United States citizens. For the suffragists who were inspired by Native women, and the feminists who continue their important work today, women’s empowerment is synonymous with women’s “rights.” But for Iroquois women, who have maintained their traditions despite two centuries of white America’s attempts to “civilize” them, the concept of women’s “rights” actually has little meaning. To the Haudenosaunee, it is simply their way of life. Their egalitarian relationships and their political authority are a reality that—for many non-Native women—is still something to strive for.

—

By Sally Roesch Wagner, Ph.D.

Collage by María Salomón

Collage left to right: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Haudenosaunee woman, Matilda Joslyn Gage

This story originally appeared in the October/November 2015 print issue of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

The Riot Grrrl Travel Guide To Olympia, Washington

Rutabega Ginsberg And 5 More Recipes For Your Feminist Thanksgiving

How Hedy Lamarr Gave Us The Cell Phone