In the 1970s, a gang of activists made history as the first—and–only American terrorist group founded and led by women. They bombed the Capitol, broke their friends out of jail, and, 40 years later, some are still at large.

It was 1981 and Marilyn Buck, Susan Rosenberg, and Judy Clark had spent days casing Co-Op City, a housing complex in the Bronx. Hours passed as they watched people and businesses, including the armored trucks that ferried cash to and from a bank.

They were there to help “the Family,” a group of self-styled revolutionaries who robbed the rich and powerful to fund radical black political activities.

Finally, on June 2, the group made their move, targeting an armored Brinks truck outside a Chase Manhattan branch, making off with more than $250,000. The three women waited in the getaway car, ready to flee. But the heist didn’t go as planned. Family member Tyrone Rison opened fire, killing one of the truck’s couriers and wounding another.

It wasn’t the first time the Family had made headlines. A few years earlier, the radical activists, along with Buck, had helped Assata Shakur (a.k.a. Joanne Chesimard), a leader in the Black Liberation Army, escape from the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women in New Jersey.

Now with the Brinks robbery, however, it was suddenly Buck, Clark, and Rosenberg—who escaped arrest but were identified in later witness testimony—who found themselves in the spotlight. The women had been essentially unknown to the FBI before the robbery, because they weren’t really members of the Family. In fact, the trio of women were rulers of their own radical organization, M19, believed to be the first—and to date only—domestic terrorist group founded and led by women. And until that botched heist, they had managed to stay completely beneath the Bureau’s radar.

M19—short for the May 19th Communist Organization and named after the birthday shared by Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X and Vietnamese revolutionary Ho Chi Minh—hoped to start an insurrection that would destroy America’s sexism, racism, and dangerous imperialism. The group included men in its ranks, but they were vastly outnumbered. And in its brief existence, M19 carried out a series of terrorist attacks, including the bombing of one of the country’s most iconic buildings. But even as radical terrorists, they faced deep-seated misogyny, and their legacy was largely ignored—until now.

This year, author William Rosenau—a military analyst whose resumé includes work as a counterterrorism expert at the State Department—released his history of the group, Tonight We Bombed the U.S. Capitol: The Explosive Story of M19, America’s First Female Terrorist Group, a book he says he wrote in part because no one else had. “I was shocked to find out that no one had ever written anything really substantial about them before and I found their [story] absolutely compelling,” Rosenau says. “In the early 20th century, women in the United States had played important roles in [groups like] the Weather Underground, but there was no comparable group that was actually organized and led by women.”

None of the surviving members of M19 would agree to an interview for Rosenau’s book, but he wasn’t deterred, spending hours combing through newspaper articles, declassified FBI documents, and grand jury transcripts and testimony. He also found a treasure trove of papers that Rosenberg donated to her alma mater, Smith College, as well as an unfinished memoir by one of M19’s two male participants, Alan Berkman, donated by his widow after his death in 2009.

Rosenau says he was also fascinated by the group’s endurance. Founded in the late ’70s, M19 existed until approximately 1985, long after many of the group’s extremist peers had either disbanded, fled, or been arrested. And what’s more, they only folded because its core members were finally caught, not because their ideals had in any way softened—if anything, they’d grown more extreme.

M19 first formed in 1978, and by 1979, they had issued their manifesto. In it, they stated their mission to be “revolutionary anti-imperialism” and declared the United States a “parasite on the Third World.”

Unofficially, M19 was an offshoot of the Weather Underground, a radical group that counted Clark as a member. The WU’s platform centered on black power and anti-Vietnam War measures. Classified by the FBI as a domestic terrorist group, it gained notoriety for the bombings of banks and various government buildings in 1971 and 1972.

They stated their mission to be “revolutionary anti-imperialism” and declared the United States a “parasite on the Third World.”

By 1977 the Underground was defunct. Clark, along with some others from the organization, wanted to further her revolutionary work, but with a focus on what she saw as the U.S. government’s cruel and brutal treatment of minorities and women—lesbians in particular. Now, M19’s members saw themselves as part of a bigger liberation movement in which, according to their manifesto, the “oppressed nations within the U.S. are preparing themselves to wage a full-scale people’s war against the enemy that has entered its final decline.” It was radical, heady stuff for a group of white women who, for the most part, came from middle-class, well-educated backgrounds.

In addition to Buck, Clark, and Rosenberg, M19 included Silvia Baraldini, Donna Joan Borup, Elizabeth “Betty Ann” Duke, Linda Sue Evans, Laura Jane Whitehorn, and two men, Alan Berkman and Timothy Adolph Blunk. At its formation, the group’s members ranged in age from their late 20s to their late 30s.

Donna Borup, 1981

Donna Borup, 1981

Clark had perhaps the most extreme upbringing. Petite with brown hair, she was once described by an admirer, according to Rosenau, as having “sparkling eyes.” She grew up in New York where her father belonged to a Marxist-Leninist group before joining the Communist Party USA. The family even moved to Moscow for a spell. They eventually ended up back in Brooklyn where her parents grew disillusioned with communism. Clark, according to Rosenau, lamented her parents’ political shift. “I couldn’t bear the loss of community and ideology and purposefulness in my life,” she would later write in the 1998 anthology, Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left. “I would be the ‘keeper of the flame’ in my family.”

The others had similar, if not quite as radical, childhoods. Rosenberg’s parents were Manhattan liberals, participating in various social justice marches and demonstrations. While attending the City College of New York, Rosenberg sported a big afro and, according to Rosenau, “found inspiration in the revolutionary women of Vietnam.”

“I saw the women of Vietnam rise up as part of their nation to say, ‘We’re going to have our own destiny,’?” she once said in an interview. “I had never seen anything like that. And I wanted to be like that.” She also worked as a drug counselor at the Lincoln Detox Center, a drug treatment program where she would eventually meet Black Panthers associate Mutulu “Doc” Shakur. A central figure in the Family—who would later become a stepfather to Tupac Shakur—Shakur was instrumental in the prison break of his friend, Assata Shakur.

Meanwhile, Buck, born and raised in Texas, inherited her activist leanings from her father, an Episcopal priest who advocated for integration, angering segregationists who once burned a cross on the family’s lawn. With high cheekbones and a fashionable wardrobe that included knee-high boots and oversized sunglasses, she looked more like a model than a radical activist. In high school, too, Buck’s interests—the campus newspaper, yearbook, drama club, and knitting—didn’t hint at her revolutionary future. That came later when she enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, where she honed her interest in the left-wing student movement.

Other M19 members followed divergent paths that led them to the same place. Baraldini was born into a rich family in Rome, where she admitted that she “lived a very privileged, protected life,” according to Rosenau. Eventually, though, she migrated to the United States and became political in college. A tomboy, Borup grew up in a working-class New Jersey family before joining members of the Moncada Library, an anti-imperialist community organizing center. Meanwhile, Whitehorn’s grandfather had been a member of the Socialist party, and the New York native became politically active while studying at Radcliffe. Born in 1945, Whitehorn was the oldest of the women, and her leanings were also influenced by her sexual identity. “My lesbianism makes me a better anti-imperialist,” she once said, according to Rosenau.

It was Duke, however, who underwent the most profound evolution. As Rosenau writes, friends described her as a typical sorority sister—a “prom girl with a beehive hairdo.” But after graduating college, marrying, and having two kids, the Texas-born Duke’s worldview transformed. By 1967, she had remarried and was supporting the farmworkers’ strike in the Rio Grande Valley.

As their politics intensified, the women of M19 eventually crossed paths through groups like the Weather Underground, where some experienced serious consequences from their involvement. In 1969, Clark was arrested for her participation in the Underground’s “Days of Rage” anti-Vietnam War protests in Chicago and served nine months in jail.

Surveillance photo of Linda Sue Evans

Surveillance photo of Linda Sue Evans

Despite their street cred, however, the women of M19 often faced sexism from within the activist community. As a member of Students for a Democratic Society, Buck appeared at a conference to give a speech about women and revolution, only to be harassed with lewd, profane jeers and wolf whistles. “Even as she continued to find work among the young radicals she admired, she was still a lonely feminist voice within the male-led, macho SDS organization,” Rosenau writes.

Before M19, these women had been going to protests, handing out pamphlets, hosting film screenings, making signs, and otherwise helping out their male counterparts. But they wanted more. And after the Weather Underground splintered, they saw a chance to take control. “They wanted to keep this armed struggle going but they thought the Weather Underground had made an important number of mistakes,” Rosenau says. There was its misogyny, for starters, and they didn’t like that they were often left out of the bigger missions, relegated to secondary tasks. But it went even deeper than that. Rosenau says that while members of the WU saw themselves as leaders of the global revolution, M19 believed its mission as anti-imperialists meant they shouldn’t center themselves in the fight but, instead, support third-world revolutions.

Soon they were staking out targets in disguises that included wigs and sunglasses, assisting with armored truck robberies, and busting their associates out of prison. In 1979, in addition to helping free Assata Shakur, M19 also helped break William Morales out of prison. Morales was a member of FALN, a Puerto Rican nationalist group. To date, both Chesimard and Morales remain at large and are on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

Susan Rosenberg

Susan Rosenberg

Even in association with the Family, however, the women of M19 resented taking on an administrative role, or what Rosenau describes as a “criminal-revolutionary take on Cold War America’s division of domestic labor.” The men would take on the heavy lifting of robberies and bombings, leaving the women behind to “print fake IDs, line up safe houses, provide perimeter security during operations, and drive getaway cars.”

It wasn’t enough. So M19, its members ensconced in clandestine homes and apartments, started making its own bombs in preparation for what would be its biggest action. It was 1983, and Ronald Reagan had been elected on a promise to shrink the U.S. government while expanding its military reach.

M19 aimed to stop Reagan’s push for American imperialism, and terrorism was part of that plan. On November 6, 1983, two female members of M19 arrived in Washington, D.C., in a car registered to Buck. Using a false name, one of them checked into a motel near their target.

The next night, at 10:48 p.m., an unidentified man called the U.S. Capitol switchboard and warned them to evacuate the building. “Listen carefully, I’m only going to tell you one time,” he said to the operator. “There is a bomb in the Capitol building. It will go off in five minutes. Evacuate the building.”

Ten minutes later, a bomb detonated in the building’s north wing. “It was loud enough to make my ears hurt,” a jogger outside said, according to Rosenau. “It kept echoing and echoing—boom, boom.”

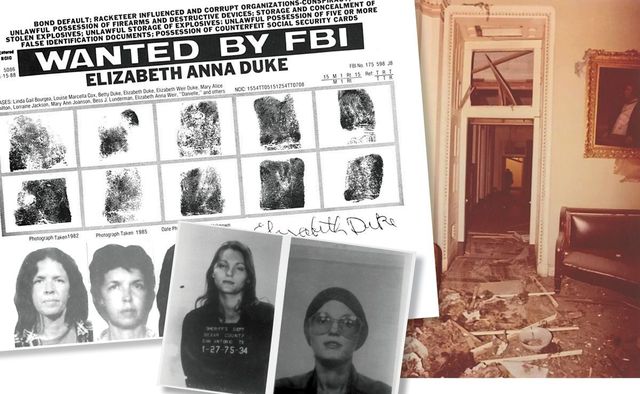

Aftermath of U.S. Capitol bombing, Nov. 7, 1983

Aftermath of U.S. Capitol bombing, Nov. 7, 1983

No one was hurt, but the explosion caused more than $1 million in damage. “The explosive load blew doors off their hinges, shattered chandeliers…and sent a shower of pulverized glass, brick, and plaster into the Republican cloakroom,” writes Rosenau. “Security guards gagged on the dust and smoke.”

It wouldn’t be the group’s only bombing. Over the course of only two years, M19 bombed several locations, including an FBI office, the South African consulate in New York, and Washington D.C.’s Fort McNair and Navy Yard (twice). But even as they grew more violent, M19 confounded terrorism experts. “The question of women and terrorism was a particularly vexing one for the specialists,” Rosenau writes. “Even though women had been key figures in terrorist groups during the 1970s—Bernadine Dohrn of the Weather Underground and Ulrike Meinhof of the Baader-Meinhof Gang were two notable examples—experts at the time tended to frame terrorism as a largely male enterprise. How could women participate in such savagery?”

It was a violent new world for the M19 women to navigate, one that forced them to make difficult choices. Clark, for example, wanted to be a mother and asked her M19 comrade, Alan Berkman, to donate sperm. She gave birth to a daughter in November 1980. At first, Rosenau writes, she was a “doting new mother, [but] the May 19th women were single-minded in their pursuit. There was no room for motherhood. At least at that moment.” Eventually, Clark agreed, reluctantly allowing her child to be raised collectively by the group so she could remain focused on its mission.

However, none of the women, according to Rosenau, were interested in the broader feminist movement of the era. “M19 supported women’s liberation, but they saw themselves as quite different from feminists like Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem—who were worried about equal pay and the Equal Rights Amendment,” he says. “They thought women’s liberation would only come about as a result of a broader revolution.”

Clark was the first to be arrested, in October 1981, just months after that fatal Brinks robbery. The group persisted, however, and before its final demise, the members of M19 grew even more radical.

M19 saw themselves as quite different from feminists like Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem. They thought women’s liberation would only come about as a result of a broader revolution.

“I think they were certainly moving toward more extreme violence,” Rosenau says, citing recovered documents that detailed new targets as well as potential assassination hits. Among their potential targets, according to an “In Progress” file that included detailed surveillance notes, diagrams, and photographs, were the Marine Corps Air Station in Quantico, VA, and the Old Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C., near the West Wing of the White House. Other possible targets, Rosenau writes, included federal prosecutors, grand jurors, and high-ranking military officers. “They were planning to keep this thing going as long as they possibly could,” he says.

But while most of them were able to elude authorities for years, the law did finally cause the group to break down. In 1985, sensing that the feds were closing in, Berkman and Duke planned to flee to Cuba, only to be pulled over by FBI agents in Pennsylvania who discovered, among other items, a loaded shotgun and a silencer-equipped 9mm pistol.

The arrest also led to the FBI’s discovery of a garage key in Duke’s purse. When the feds raided the garage, they found a stockpile of cash, weapons, and pamphlets such as “The Women’s Gun Pamphlet” and “Five Steps to Good Shooting.” The garage was also stocked with 86 pounds of dynamite, stored so haphazardly that it made the space a literal ticking time bomb. The FBI dusted for fingerprints and found enough to link the place to every member of the group and make more arrests.

Surveillance photo of Marilyn Buck

Surveillance photo of Marilyn Buck

The fallout was swift. Buck was convicted on various crimes, including the Brinks robbery and the 1983 U.S. Senate bombing. She served time until July 2010, and was released less than a month before her death, at age 62, from cancer.

Duke and Borup remain fugitives to this day. Duke jumped bail and fled the country in 1985. Borup, who was arrested in 1982, failed to appear at trial, and is currently on the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorist list.

Convicted a year before the garage raid in 1984, Susan Rosenberg remained behind bars until 2001 when then-President Bill Clinton commuted her sentence.

Clark was paroled in 2019, after nearly 40 years in prison.

“They’ve been forgotten…[but] their stories still have a lot to tell us about our own history, about terrorism, and about who becomes a terrorist and why,” Rosenau says. “It’s all about belief and belonging and there are things that we can tease out of their story that still have relevance today.”

By Rachel Leibrock

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

How China’s First Female Emperor Schemed Her Way To The Top

Your Feminism Isn’t Intersectional If It Doesn’t Include Prison Abolition

We Know The Schuyler Sisters — Now, Meet The Other Real-Life Women Behind “Hamilton”