“Just like the men!” Cartoon. New-York Tribune, March 1, 1913

When African-American women demanded the right to vote, they faced resistance from racists, from sexists, and even from other suffragists

By Sabrina Ford

America’s recent presidential election was a painful one for many of us. But amid all the traumatic sound bites, one of the few highlights was watching women in their late 90s and older—born before the 19th amendment granted women the right to vote—gleefully casting their votes for a female president for the first time.

Of course, Hillary Clinton’s historic nomination and campaign was the perfect excuse to revisit the long and difficult fight for women’s voting rights. Celebrating American suffragists was a running theme during the election. And in the days leading up to November 8, the hashtag #WearWhiteToVote was trending on Twitter as many women shared plans to pay tribute to the suffragists by wearing all white to the polls.

But on the eve of the election, best-selling author and blogger Luvvie Ajayi voiced what so many black women feel when the suffragists are spoken about with reverence. “I’m surely not wearing white tomorrow,” Ajayi tweeted, calling the suffragists “the epitome of white feminism.” Journalist Britni Danielle replied to the trending topic by posting, “If anything, I’ll wear red, black, and green, for the BLACK suffragists who were pushed out but worked anyway.”

The complicated reality of the women’s suffrage movement is that the very women who are heroes to white women for securing their right to vote often excluded black women from participating in the movement, and worse, even made the argument for their right to vote by exerting their superiority over African Americans. Although many prominent white suffragists had publicly opposed slavery and supported equal rights for African Americans, black women were often barred from joining women’s rights organizations or marginalized within those organizations. The divide between the movements for equality for white women and equality for black women was established early and, unfortunately, remains today. So while the nomination of Hillary Clinton was historic for all women, the celebration of the suffragists is, for women of color, a painful reminder that the mainstream women’s movement in America has a long history of being focused mostly on the needs and desires of middle-class and well-to-do white women.

In July 1848, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who’d both been active in the abolitionist movement to end slavery, held the first conference for women’s rights in Seneca Falls, New York. While there were no black women in attendance, former slave and famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass was invited to speak. Douglass expressed his gratitude for Mott and Stanton’s support of abolition and pledged his support to the women’s suffrage movement. Douglass remained active in the suffrage movement for years, forming a friendship and close working relationship with suffragist Susan B. Anthony.

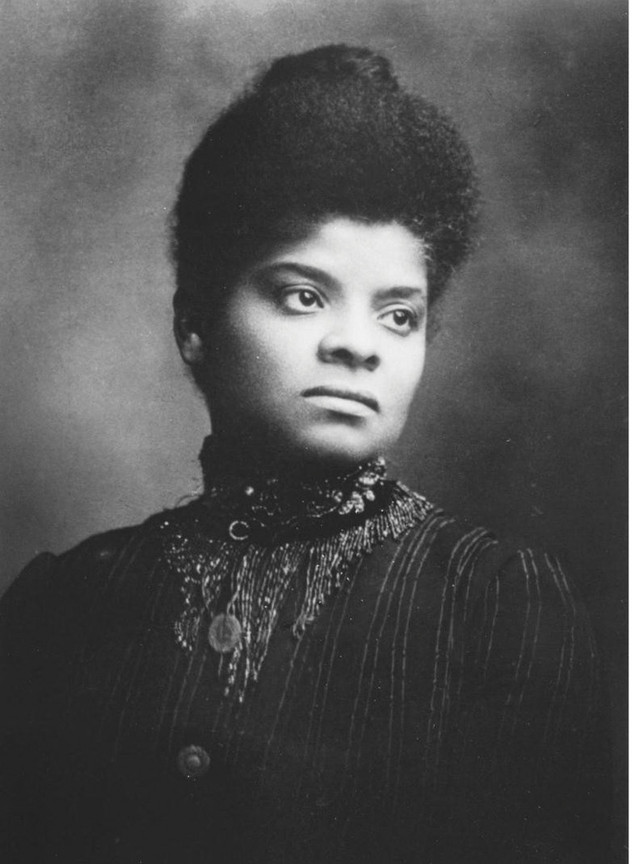

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Photo: Library of Congress

But things got ugly with the proposal of the 15th Amendment, in 1869, which stated that no one could be denied the right to vote on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Suffragists fought against the 15th Amendment because it did not seek to remedy the denial of voting rights based on gender. Anthony famously said, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.” But abolitionists and Republicans were intent on prioritizing black men’s suffrage over that of women. Stanton, Anthony, and other prominent suffragists responded to this sexism by adopting anti-black arguments for women’s suffrage and courting the support of racists who opposed black men’s right to vote. Arguing that white women should be granted the vote in order to counteract the votes of newly enfranchised black men and the growing number of immigrants, Stanton wrote, “The best interests of the nation demand that we outweigh this incoming pauperism, ignorance, and degradation with the wealth, education, and refinement of the women of the republic.”

This rhetoric was particularly troubling to black suffragists like Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the latter of whom first came to prominence as an activist against the common and horrific practice of the lynching of African Americans. Wells-Barnett, who in her autobiography, Crusade for Justice, called Susan B. Anthony a “dear friend,” recalled a conversation she’d had with Anthony about Frederick Douglass’ participation in the suffrage movement. Anthony told Wells that when her suffrage organization went to Atlanta, she asked Douglass not to attend because, “I did not want to subject him to humiliation, and I did not want anything to get in the way of bringing the Southern white women into our suffrage association, now that their interest had been awakened.” In other words, she didn’t want to upset racist white Southerners who may have been open to the idea of white women voting, but would have balked at the sight of Douglass, a former slave.

According to Wells-Barnett, Anthony also told her that she had refused some black suffragists’ requests for assistance for the same reasons, telling her, “When a group of colored women came and asked that I come to them and aid them in forming a branch of the suffrage association among the colored women, I declined to do so, on the ground of that same expediency.”

But while their white counterparts used racism to argue for the importance of women’s suffrage, some black suffragists also felt it was imperitive that, if black men were to be granted the right to vote, women must be given that right as well. For these women, many of whom had until recently been the property of white men, living in a society where their husbands had the vote and they did not was tantamount to another form of slavery. Black abolitionist and suffragist Sojourner Truth addressed these concerns specifically when she spoke in New York City at an 1867 convention of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), the suffrage organization presided over by Lucretia Mott. “I feel that I have the right to have just as much as a man,” she told the crowd. “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.”

“I will cut off this right arm of ?mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.” ?Susan B. Anthony, 1869

Anthony and Stanton further distanced themselves from black suffragists when they co-founded The Revolution—a newspaper focused on women’s rights—with funding provided by Democrat and pro-slavery businessman George Train. Train actively campaigned against enfranchising freed black men, announcing, during an 1867 women’s rights speaking tour, “Woman first, and negro last, is my programme.”

There were, however, a good number of white suffragists who rejected the anti-black attitudes of many of their peers. Mott broke with Anthony and Stanton over their opposition to the 15th Amendment, and resigned from her position as President of the AERA. Born into a Quaker family, Mott was also a minister who had helped organize the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women. Nevetheless, her split from Anthony and Stanton was not an easy one. “Altho’ they make some mistakes,” she said of the pair when it seemed a schism in the movement was imminent, “I can’t bear to have them ignored in any way.” For activist Lucy Stone, another leader in the suffrage movement, the pairs’ association with Train was completely unacceptable. “She stayed late and talked much against Train and Anthony,” Mott wrote, regarding a visit she’d had from Stone. “No chance of reunion.”

“If colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.” ?Sojourner Truth, 1867

As a result, in 1869, more than 20 years after its first meeting in Seneca Falls, the women’s suffrage movement finally split into multiple factions. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), created by Anthony and Stanton, actively opposed the 15th Amendment because it excluded women. Although Mott supported suffrage for all regardless of color or sex as president of the American Equal Rights Association, she was also an active member of the NWSA. Critical of the NWSA’s divisive agenda, Stone—along with Henry Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, and others—founded the American Women Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported ratifying the 15th Amendment even if it meant women would have to wait before they could win the right to vote. “I thank God for that 15th Amendment,” Stone stated, “and I hope that it will be adopted in every state.” In contrast to the all-female and all-white membership of the NWSA, the AWSA made “no distinctions because of race,” and “no distinctions because of sex,” and, as a result, counted people of color and men among its membership. Stone—who was such a badass she kept her maiden name and formally rejected laws making her a subordinate when she married in 1855—was both an outspoken suffragist and abolitionist. A radical among her fellow organizers, Stone believed in freedom for African-Americans by any means necessary, stating, “I do not know what bloodshed may come by it. All I do know is, that we have no right to keep a Union with slaveholders. Slavery shall be abolished, or the Union shall be dissolved.”

As passionate as some white suffragists were about progressing the cause for all women, the task still fell to women of color to organize and empower the black community for the advancement of their own interests. Bi-racial journalist, suffragist, abolitionist, and AWSA co-founder Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin worked alongside Stone and Howe in Boston before branching off into endeavors more specifically geared toward women of color. In 1890, St. Pierre Ruffin founded a monthly journal called The Woman’s Era, the nation’s first newspaper published by and for African-American women, and her freelance journalism spread the message of suffrage outside the movement as well. In a 1915 article titled “Trust The Women!,” which she penned for the NAACP magazine The Crisis, St. Pierre Ruffin wrote, “Many colored men doubt the wisdom of women’s suffrage because they fear that it will increase the number of our political enemies…. [But] we are justified in believing that the success of this movement for equality of the sexes means more progress toward equality of the races.”

Alongside her daughter, St. Pierre Ruffin also organized an advocacy group for women of color in 1894 called the Women’s Era Club. In 1896, they merged with the Colored Women’s League of Washington, D.C., and the National Federation of Afro-American Women to become the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). Dedicated to “raising to the highest plane the home life, moral standards, and civic life of our race,” the NACWC also claimed as one of their core objectives, “To secure and use our influence for the enforcement of civil and political rights for African Americans and all citizens.” But when St. Pierre Ruffin tried to take her group to a conference being held by the General Federation of Women’s Clubs in Milwaukee in 1900, the executive committee of the conference voted to rescind their invitation when it was discovered that the delegation was black. The situation was covered by the national press and was referred to as “The Ruffin Incident.” In the wake of their exclusion, the Women’s Era Club released an official statement denouncing the committee’s decision while questioning whether women who would stoop so low could actually be trusted with voting privileges. It read in part: “Shall women, asking for suffrage and a large participation in public life, endorse a ruling which, as a specimen of bossism, could not be overmatched by the lowest political gathering in the country?…. We regret to see the standard lowered, the higher ideals repudiated, and the power of the club work diminished by any declaration that it is the cause of white women for which it stands, and not the cause of womankind.”

Sojourner Truth

Photo: Library of Congress

In the meantime, the NWSA and the AWSA had overcome their differences in favor of a more centralized movement and, in 1890, merged to become the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). At the time of their formation, the group had 7,000 members, but their ranks steadily increased to 2 million, making NAWSA the largest voluntary organization in the nation. Positioning themselves as a more progressive organization than the divisive NWSA, NAWSA invited civil rights activist and suffragist Mary Church Terrell to speak on “The Progress of Colored Women,” at their 1898 meeting in Washington D.C. “Consider if you will, the almost insurmountable obstacles which have confronted colored women in their efforts to educate and cultivate themselves since their emancipation,” she told the assembled crowd. “I dare assert, not boastfully, but with pardonable pride, I hope, that the progress they have made and the work they have accomplished, will bear a favorable comparison at least with that of their more fortunate sisters, from whom the opportunity of acquiring knowledge and the means of self-culture have never been entirely withheld. For, not only are colored women with ambition and aspiration handicapped on account of their sex, but they are everywhere baffled and mocked on account of their race. Desperately and continuously they are forced to fight that opposition, born of a cruel, unreasonable prejudice which neither their merit nor their necessity seems able to subdue. Not only because they are women, but because they are colored women, are discouragement and disappointment meeting them at every turn.”

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

Despite this gesture of inclusivity, however, NAWSA revived the movement’s earlier penchant for white supremacy when they organized a segregated March for Women’s Suffrage in Washington, D.C., in 1913. Spearheaded by Alice Paul, the march marked the first public appearance of the black Delta Sigma Theta sorority, founded at Howard University that same year. But members of the sorority, and other black women, were asked by Paul to march at the very back of the parade because some white suffragists refused to march alongside women of color. Wells-Barnett, already a prominent figure by then in the Chicago suffragist movement, staunchly rejected this notion, and replied that she “refused to take part unless I can march under the Illinois banner.” Ultimately, she did end up marching alongside the white feminists from her home state. According to some accounts, she accomplished this by hiding in a crowd of spectators before jumping into the white segment of the procession mid-parade.

Mary Church Terrell

Photo: Library of Congress

That same year, Wells-Barnett organized the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, believed to be the first black women’s suffrage organization. The club campaigned tirelessly not only to secure the right to vote, but also to elect local candidates of color and to put an end to lynching. They played a significant role in the passing of the Illinois Presidential and Municipal Suffrage Bill in 1913, which allowed all women in the state to vote for Presidential electors and for some local officials. But even in races where they had not yet been granted the vote—as was the case with Illinois circuit court judges—they educated themselves on the candidates because, as they told the press in an official statement, they still felt it was their duty to “use their influence to aid in selecting good judges,” usually through their husbands’ votes.

Colored Women Voters League. Georgia, circa 1920

Photo: Used with permission of the Schomburg Center for Black Culture

After the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave all American women the right to vote, the struggle for equal rights in other aspects of society transformed the suffrage movement into the feminist movement. And in the wake of this transition, predominantly white women’s organizations continued to take center stage as the second-wave feminists fought for women’s equality in the workplace and the right to choose in the ’60s, and for the Equal Rights Amendment in the ’70s. But that doesn’t mean women of color dropped out of the movement or ever stopped struggling to be considered equal—both by society at large and by white feminists.

Activist and author Audre Lorde eloquently gave voice to this struggle in 1979, while addressing a room full of second-wave feminists at the Second Sex Conference in New York. In a speech that was later printed as “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” she declared, “Women of today are still being called upon to stretch across the gap of male ignorance and to educate men as to our existence and our needs. This is an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns. Now we hear that it is the task of women of color to educate white women—in the face of tremendous resistance—as to our existence, our differences, our relative roles in our joint survival. This is a diversion of energies and a tragic repetition of racist patriarchal thought.”

“Not only because they are women, but because they are colored women, are discouragement and disappointment meeting them at every turn.”

Mary Church Terrell, 1898

More from BUST

A Primer On Women And Civil Disobedience

4 Things Men Need To Do Before They Call Themselves Feminists