Growing up, I knew what it felt like to be brown. I knew that going over to my friend’s house for dinner meant that my mom would think I was malnourished when I came back. I knew that I dreaded being out in the sun for too long because that meant I got darker, and God forbid I get darker. I knew that I would feel ashamed when my mom talked too loudly in Spanish, or I had to translate for her.

Being brown – for me – meant that as a kid, I constantly compared myself to people who were fundamentally different from me. My “friends” hated eating with my family because our food was too spicy and thought the fact that Spanish is my first language was really weird. “You’re one of those?!” they would ask. It seemed like most of my friendships were conditional on how much I assimilated into White Suburban American culture.

Although as a child I was very aware of the fact that I was not white, I never once thought about my gender. I knew I was a girl because during our daily Boys Chase Girls games at recess, I was always being chased. However, I didn’t know what it meant to be a girl in the same way that I knew what it meant to be a girl of color. In fact, it wasn’t until I was nine years old that it hit me. Mainly because a man hit on me. The summer after I turned nine, my family went to Mexico to visit some of my mom’s relatives. We stayed at my uncle’s guest house, and he had a ton of handymen around working on various jobs.

One of them – he must have been in his mid-20s – was creepily fascinated by me. He would attempt to talk to me, and I once overheard him telling my younger brother that he “liked me” and “thought I was pretty.”

I was very confused. I remember how my mom would tell my brothers and I that if an older person ever tried to touch us inappropriately, we should tell her immediately. It never got to that point, but for the entire rest of the visit, I was afraid to go near him. I would fake sick if he was invited to dinner. I would look out my window to see if he was there before deciding whether or not to leave the house.

I never told my mother about the handyman’s weird obsession with me. In fact, I haven’t really told anyone until now. That disturbing occurrence was a monumental turning point in my life. I realized I was a girl of color. Or rather, in that man’s eyes, a woman of color. At nine years old.

I asked some people whether I should post this very private experience in a public forum, and I received an overwhelming amount of support. Many other women of color told me that they had experienced something similar when they were younger, which proves how important it is to talk about these situations. The hypersexualization of girls of color is real, and I shouldn’t have had to cover up as a nine-year-old to avoid male stares.

I grew up in Dallas, Texas, and I’m still digesting everything that went on there, good and bad. My childhood memories are of Mexican grocery stores filled with people that looked and spoke like me. My parents had many friends, and I wasn’t the token brown girl in most social circles. In high school, however, it was different.

My high school was mostly white. I didn’t have the vocabulary to practice critical race theory back then, so I just silently observed social patterns between the kids of color and the white kids. I was often treated differently because I passed as white.

I knew that if I spoke out about my experience, my friends would think of me differently. So I stayed quiet. When I noticed racism towards others, or myself, I stayed quiet, at least until I arrived at college.

During my freshman year, I joined the debate team and several community service groups. I learned about gender theory, and finally started identifying as a feminist, although I probably always was one.

I started talking about feminism with people who ultimately cared nothing about me and my struggles, especially my debate teammates. I thought they might understand what I had gone through. I tried to become more like them, even if it meant muting certain parts of my identity. Sometimes, I was too much of a feminist. Sometimes, I was too brown. Most of all, it was too much to be a woman of color. No one wanted to talk about the intersection of race and gender. Once, at the end of a debate round, someone even said, “We were talking about gender, why would she bring up cultural appropriation?”

At home, I was hyperaware of racism. But here, people seemed to think that if we didn’t talk about it, it would go away. This type of erasure regulated any woman of color who brought up race as “counterproductive,” “angry,” or “antagonizing.”

As time went by, and I realized that staying on the debate team meant giving up who I was and assimilating to this weird, white, liberal culture circulating throughout the debate circuit. Instead, I got more involved in community service. I often served people with backgrounds similar to mine, and considered my work less community service and more being a decent human lending a helping hand. Here, people got medals for it. I wondered where my mother’s medals were.

I didn’t get to the point where I am now until this past semester. Sophomore year, I officially ended what was left of my relationship with the debate team, aside from a couple of friends. Someone dropped a racial slur during a final round, and I finally realized that I didn’t really mean anything to these people. And it wasn’t just because I wasn’t “good.” It was because, in the end, it was fine to drop a casual racial slur but too much for me to talk about cultural appropriation.

I’ve also become more involved in activism this year, especially the Feminist Majority group on campus. I’ve started writing more about how I felt about racism on campus. I’ve adopted Assata Shakur’s phrase “reluctant struggler” and realized that this is what I am, not because I just wanted to be an activist, but because I had to be.

I can no longer stay quiet and watch other young girls of color struggle with who they are. I can’t sit back and watch men sexualize little girls because of their intersecting identities. I need to be there for these girls.

I know firsthand how awful these conflicting worlds can be for girls of color. I have overcome internalized racism, the racism of others, and perpetual erasure. I know all of that had to happen for a reason. Yes, it’s hard, but I’m committed to life.

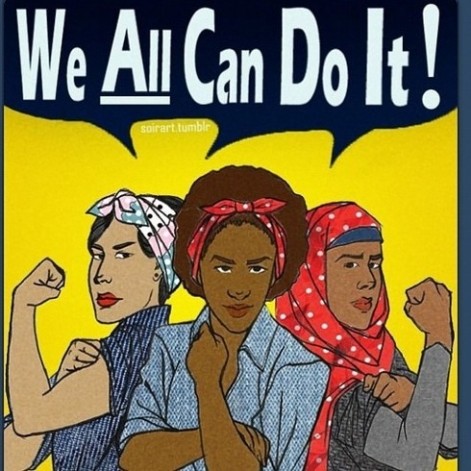

Photo via the hotness.com and lavidaesfacilydivertida.com. Art Installation in Madrid. “For all the women who have silently created history.”