For some enlisted men, The War Between the States involved a struggle between two identities. Hidden among the ranks of both the Union and Confederate armies were women in disguise, who fought and died for the cause—or lived to tell their incredible tales

In May 1862, a young, grey-eyed, black-haired soldier was discharged from the 17th Ohio Infantry in Corinth, Mississippi, despite having served well since signing up soon after the Civil War began in 1861. The reason for the soldier’s rejection from the regiment? Regardless of the fact that Pvt. Frank Deming had been sick “no days” in the past two months, the certificate of disability for discharge stated that the soldier was “incapable of performing the duties of a soldier” because of “a congenital peculiarity which should have prevented her admission into the Army—being a female.”

Pvt. Frank Deming’s Discharge Certificate, which lists the soldier’s disability as “being a female.”

Pvt. Frank Deming’s Discharge Certificate, which lists the soldier’s disability as “being a female.”

Like many other women who took up arms for the North or the South during America’s bloodiest conflict, Pvt. Frank Deming’s real identity, the circumstances surrounding the soldier’s enlistment, and what happened to Deming after leaving the army remain a mystery. Numerous female fighters took their secret to the grave and were only discovered to have been women by burial parties on the battlefield, or long after the fight was over, when archeological teams reinterred mass graves of soldiers. But not all women who served did so in secret, or at least not for long: newspapers of the day were filled with stories of heroines who had gallantly donned the blue or the gray and marched off to war. Many of them were loath to be left at home by a loved one who had signed up, including one young wife so desper-ate to stay by her husband’s side that she attempted suicide when she was discovered in the ranks of the 19th Illinois and ejected from the regiment, unable to follow her husband to war. “I have only my husband in all the world,” she said, in explanation for her enlistment.

But the reason for a woman to cut her long tresses, discard her skirts, and adopt a male persona for the purpose of enlisting was not always romance. Victorian America’s social, legal, and economic system presented huge barriers to women, who were generally restricted to home front concerns. So at the outbreak of the Civil War, when tens of thousands of men left their farms or mundane factory jobs to see the country as soldiers, the opportunity appealed to the ladies as well. For farm and frontier women who labored in the fields and already knew how to handle a rifle, army life was not far removed from their home experiences, and it offered pay and more freedom. Other women seized the chance to leave the drudgery of toil as domestic workers and answer the call to arms. Still others sought to find success and fame beyond their own four walls.

Pvt. Lyons Wakeman, aka Sarah Rosetta Wakeman

Pvt. Lyons Wakeman, aka Sarah Rosetta Wakeman

Many of these soldiers dropped their disguises as soon as the war was over and returned to their husbands and families. But some were already living as men before the war, and continued to do so for the rest of their lives. Whether those folks presented themselves as males because it allowed them to work or collect pension, as it is most often explained, or whether living as a man was their own personal preference, we’ll never know. But in an age in which there were no Social Security numbers and women were rarely glimpsed wearing pants, it was relatively easy for a woman to slip into the identity of a man by simply adopting male attire and a convincing backstory. And both armies were eager to sign up all comers with few questions.

Sarah Emma E. Edmonds dressed as a woman

Sarah Emma E. Edmonds dressed as a woman

Sarah Rosetta Wakeman was typical of the women who joined the military for financial, as opposed to patriotic, reasons. Rosetta, as she called herself, grew up ona farm in upstate New York as the eldest child of nine. At age 17, she was listed on the 1860 census with an occupation of “domestic.” Two years later, she left home. As she wrote to her family, “I knew that I could help you more to leave home than to stay there with you. So I left.” She adopted male attire and a new identity as Lyons Wakeman and went to the nearest large city to look for work. There she signed on to do manual labor on a coal barge. At the end of her first run, she encountered recruiters from the 153rd New York State Volunteers. They offered her $152 in bounties and pay to sign up for three years in the Union Army. For a 19th-century girl with no prospects of marriage, few work skills, and a father who was deeply in debt, it was an offer she couldn’t refuse.

Edmonds in men’s clothing as Franklin Thompson

Edmonds in men’s clothing as Franklin Thompson

She went on to serve almost two years with the 153rd New York Volunteers under the alias Pvt. Wakeman. She marched over 400 miles and fought in two battles. Although she kept her secret from the Union Army, her family and friends knew she was a soldier. She dutifully wrote home to them on a regular basis and tried to send them money when she was able. Her letters, which survived in descendants’ attics until discovered and published in 1995, are the only collection by a female Civil War soldier known to exist. “I like to be a soldier very well,” she wrote in one, alerting her family that she would soon be going “into the field of battle. I don’t feel afraid to go. I don’t believe there are any Rebel’s bullet made for me yet. Nor I don’t care if there is.”

Illustration from her best-selling memoir, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, showing her helping a female soldier also disguised as a male

Illustration from her best-selling memoir, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, showing her helping a female soldier also disguised as a male

In the end, it wasn’t battle but disease that took Wakeman out of the soldier’s ranks. She became one of the thousands of troops to fall sick in the steamy Louisiana backcountry. It took two weeks to move Private Wakeman by wagon to the general hospital in New Orleans, where she languished for a month before succumbing to her illness. She was never discovered to be a woman by her fellow soldiers, and is buried under her male alias in Chalmette National Cemetery.

Another patriotic woman, Sarah Emma E. Edmonds, enlisted in the 2nd Michigan as Pvt. Franklin Thompson in May, 1861, shortly after the war brokeout. In later years Edmonds wrote that, as she was preparing to go to the front and watched women bid their husbands and sons farewell, she “could only thank God that I was free and could go forward and work, and was not obliged to stay at home and weep.” She rendered nearly two years of service before becoming ill with malaria and deserting because, she wrote, she did not want to be discovered and rejected from her regiment. “I would rather have died,” she said. During her service, she performed duties as a nurse, mail carrier, spy, and as an orderly to a brigadier general at Fredericksburg (a particularly difficult and bloody battle for Union forces).

After leaving the ranks, Sarah Edmonds wrote her memoirs and had them published under the title Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. In this entertaining account of her wartime experiences, Edmonds recounts coming across a soft-faced soldier while tending the wounded at Antietam. The surgeon declared that this boy would not survive his grave injury and moved on to treat others, but Edmonds decided to stay with the patient and comfort him until he passed away. Sensing a compassionate soul, the young soldier confessed to Edmonds that he was really a young woman who joined to be with her brother, and that her brother had died in battle earlier that day. Edmonds honored the soldier’s wishes to be buried anonymously, writing that she “carried her remains to a lonely spot…and gave her a soldier’s burial, without coffin or shroud, only a blanket for a winding sheet.” No one would ever know this woman’s true identity.

Nurse and Spy in the Union Army was a bestseller in 1864, and Sarah Edmonds donated the proceeds to the care of wounded Union Soldiers. Later, she married, had three children, and lived quietly with her husband and family at Fort Scott, Kansas, until her health declined and her medical bills rose due to injuries suffered during her army service. She then began a campaign to lobby Congress to wipe the charge of desertion from her record and to receive a pension. With the help of her former comrades in arms, she was success-ful in her quest for official recognition of her military service when Congress approved a resolution to clear her record and grant her a soldier’s pension in 1886.

Deposition from one of Cashier’s comrades, in which he states that he never suspected that Cashier was a woman, but did note that he never shaved

Deposition from one of Cashier’s comrades, in which he states that he never suspected that Cashier was a woman, but did note that he never shaved

The case of Jennie Hodgers, alias Pvt. Albert D.J. Cashier, is particularly fascinating. This Irish immigrant enlisted in the 95th Illinois and served for three years undetected, fighting with the regiment under Generals Grant and Sherman on the march toward Vicksburg and on the front lines of that siege. Private Cashier, having lived as a man prior to the war in order to make a living, continued to do so after the war. Cashier was illiterate, but was well loved by friends in his town of Saunemin, Illinois, who had no idea that he was born female. The truth came out very slowly, and many of Cashier’s good friends and employers kept the confidence for many years. They even helped the veteran obtain a pension and entrance into an Old Soldier’s Home when his health began to decline. It was only when Cashier was declared insane and committed to an asylum that the Pension Bureau caught wind of the scandal and began an in-depth investigation of whether or not the elderly veteran was indeed the same youth who had enlisted in the 95th Illinois all those years ago.

Pvt. Albert D.J. Cashier

Pvt. Albert D.J. Cashier

After gathering affidavits from all of Cashier’s comrades that could be located, the Pension Bureau determined that the person in the insane asylum had, indeed, served three years in the Union Army and was deserving of the soldier’s benefits collected. Cashier’s fellow soldiers remembered him as the smallest man in the regiment, but “a very brave little soldier.” Another wrote that although they often speculated about Albert’s lack of a beard, they “never dreamed he was a woman.”

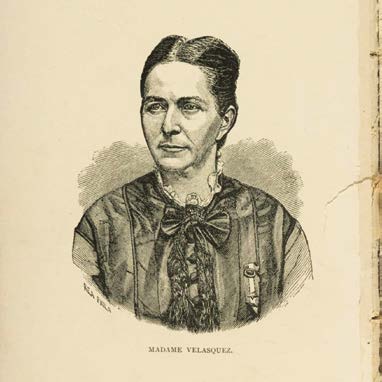

Unfortunately, not all women who fought in the Civil War took up the Union side. Confederate solider Loreta Velazquez enlisted in the rebel army as Lt. Harry Buford, although her reasons for doing so seem to be more personal than political. By age 20, Velazquez had already been married for five years and had given birth to three children, each of whom had died. As she writes in her 1876 memoir, The Woman in Battle, “my grief at their loss probably had a great influence in reviving my notions about military glory…I felt that now the great opportunity of my life had arrived, and my mind was busy night and day in planning schemes for making my name famous above that of any of the great heroines of history, not even excepting my favorite, Joan of Arc.”

Cashier at age 67

Cashier at age 67

She eventually convinced her husband that she would rather go to battle with him than be left home alone, and he agreed to help her develop her disguise, taking her with him to a bar to test it out. Recalling that evening, she wrote: “Braiding my hair very close, I put on a man’s wig, and a false mustache, and by tucking my pantaloons in my boots, as I had seen men do frequently, and otherwise arranging the garments, which were somewhat large for me, I managed to trans-form myself into a very presentable man. As I surveyed myself in the mirror I was immensely pleased with the figure I cut, and fancied that I made quite as good look-ing a man as my husband. It was not long before we were in the street, I doing my best to walk with a masculine gait, and to behave as if I had been accustomed to wear pantaloons all my life. I confess, that when it actually came to the point of appearing in public in this sort of attire, my heart began to fail me a little; but I was bent on going through with the thing, and so, plucking up courage, I strode along by the side of my husband with as unconcerned an air as it was possible for me to put on.” Her transformation complete, she joined the Confederate Army and galloped off to war, participating in every battle on the eastern front, from Ball’s Bluff through Shiloh.

A Confederate solider who won the attention of newspapers across the South after her identity was discovered was Mary Ann Clark. Her story came out in 1862, at a time when the Confederacy was running into manpower shortages and was contemplating a draft to fill the ranks. Clark, who was said to serve under the name Henry Clark, was hailed as a heroine in Southern media and was held up as an example to the men at home who should be enlisting. “Miz Clark” reportedly enlisted with her husband, who was killed by her side on the battlefield at Shiloh.

That was the story as either she told it to journalists or as the newspapers chose to interpret it. However, a letter from Clark to her mother, and her mother’s 10-page response, tell a decidedly different version of things. According to Clark’s mother, her daughter was married to an abusive and unsupportive man who left her and their two children to go to California and marry another woman. He then wrote home to inform his family that he was returning with his new wife. This drove Clark into a deep depression. Her mother wrote that “a dark gloom seemed to hang over her which seemed to thicken and grow more and more lowering…she often spoke of going into the army, yet strange it never occurred to me she would really make the attempt. She left home in Oct. ’61 in the night and the first news we obtained…[was] she had united with a cavalry company under the assumed name of Henry Clark.”

Clark’s first enlistment lasted until February 1862, when she returned home. The death of a favorite relative at the hands of Unionists sent her back into the army in June that year, but she was captured and sent to a Union prisoner of war camp after her wounding at the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky. It was there that she was discovered to be a woman. In a letter to family, she wrote, “I arrived safely at this place and have been treated like a lady….Tell [mother] that I never expect to see her again, as I may get killed in battle. There is a battle impending at Vicksburg and I expect to be in it. Our officers here tell me that they will exchange me for a man. Tell her what a good rebel soldier I have been.” Clark was in fact traded for a male Union soldier, and rejoined the Confederate ranks once again. This time, she served openly as a woman. She was given her due by the army with a promotion to lieutenant serving in Gen. Braxton Bragg’s command on the western front in January 1863.

Letter from Mary Ann Clark, with a message for her mother. “Tell her I never expect to see her again.”

Letter from Mary Ann Clark, with a message for her mother. “Tell her I never expect to see her again.”

The aforementioned are just a few of the over 250 documented cases of women disguising themselves to enlist as soldiers for the Confederacy or the Union. These female soldiers bore all the same rigors and horrors of army life as their male comrades, and did so under the additional burden of having to maintain a new and different identity. They endured thousands of miles of hard marching, bad diets, disease in camps, death and wounding on the battlefield, and capture as POWs. A handful actually served unnoticed until they gave birth. Their comrades expressed admiration for them in letters and diaries when females were revealed to be among their ranks, and often wrote of their surprise to learn that a certain “soldierly fellow” or a “cpl who had since been promoted to sgt for gallantry on the battlefield” was, in reality, a woman.

Whether it was for love of a husband, love of country, financial need, or freedom from drudgery that originally motivated them to enlist, the women who committed to army life ultimately did so for the same reasons soldiers have stated for centuries—for their country, and to support their comrades in arms. It would be over 50 years after the end of The Civil War before a new wave of brave American women won the next great battle—that of the right to vote in the nation they had fought to save.

—

by Lauren M. Cook

Lauren M. Cook co-wrote They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in The Civil War (Penguin Random House) with DeAnne Blanton.

Photographs courtesy of Lauren M. Cook, The State Archives of Michigan, Illinois State Historical Library and Trading Cards-National Park Service, and Kentucky State Archives

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2015 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

An All-Caps Explosion of Feelings Regarding the Liberal Backlash Against Hillary Clinton

Beyoncé’s ‘Formation’ Is An Ode To Black Pride