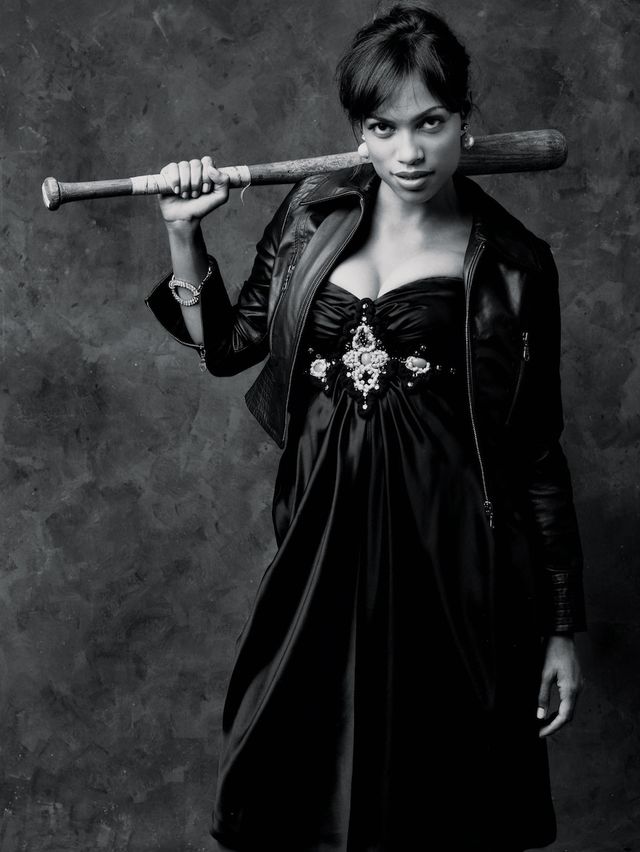

To celebrate BUST’s 25th anniversary, we’re bringing some of our favorite cover stories online. Here’s our interview with Rosario Dawson from our August/September 2007 Fashion & Music issue.

Screen siren Rosario Dawson has spent the last 13 years transforming a chance encounter into a career chock-full of roles that keep women riveted. Here, she opens up about movies, her mom, and standing by the choices she makes.

Rosario Dawson is so naturally dynamic that she landed her first feature role in the movie Kids at the age of 15, just by being herself: she was hanging out, laughing with her friends on a stoop in her neighborhood on New York’s Lower East Side, when writer/director Larry Clark walked by and cast her on the spot as Ruby, a sexually-active teenage spitfire. Since then, she’s become a phenomenal force on film—working with A-list directors like Spike Lee in 25th Hour (2002) and Oliver Stone in Alexander (2004)—as well as in activism, lending her voice and image to Global Cool, a group that raises awareness about climate change and the environment, and cofounding Voto Latino, which seeks to register Latino voters and widen the role of Latinos in politics.

Whatever role the 28-year-old has played, she’s risked being upstaged by her uncanny natural beauty—the result of her Puerto Rican, Cuban, African-American, Irish, and Native American heritage. After her early success in Kids (1995) and a follow-up part as a sexy teenager in Spike Lee’s He Got Game (1998), she could easily have made a career out of what she’s called “hoochie roles,” playing the hot, sexy, around-the-way girl in film after film. But she transcended the stereotype, playing roles from rock star (in 2001’s Josie and the Pussycats) to journalist (in 2003’s Shattered Glass); she’s been an Uzi-toting hooker (2005’s Sin City) and a geeky girl next door (in Kevin Smith’s 2006 Clerks II—a role she says she took, in part, because of the movie’s infamous sex scene between a man and a donkey). Now she’s producing her own movies and even co-writes and models for a comic book, Occult Crimes Taskforce.

But no matter what she’s doing on camera, Dawson is an activist at heart. When we speak by phone, she is in Cannes promoting Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof, in which she stars, and the screening of her first coproduction, Descent (opening in limited release in October). Between discussing the films, she’s blistering my ear with a rapid-fire rant that jumps from topic to topic—sexual violence, AIDS in Africa, beauty standards in Hollywood—sounding like she’s ready to fly right to the source of the injustice, whether it’s Nicaragua (where she recently joined a poverty-relief effort with Operation USA), or her native New York City (where she’s a major sponsor of the Lower Eastside Girls Club of New York). For someone who’s usually seen floating along red carpets, she sounds like a woman whose feet are firmly on the ground.

Tell us about the movie you just starred in and co-produced [with your old acting-school friend Talia Lugacy], Descent.

Descent is a film exploring sexual violence. I play a college student—she’s really smart, outspoken, and opinionated, but she’s lonely and kind of keeps to herself. So she meets this guy, and they go on a date. And she has an inkling that he might not be the right kind of guy for her, but she’s curious about him and he tries really hard to woo her—and then he date-rapes her. And she doesn’t do what you might think someone as smart and outspoken as she is would do: she shuts down, and she doesn’t tell anybody. Because she blames herself, she thinks she should have been smart enough not to put herself in that situation. But now she knows it’s not about being smart; it’s about the fact that there are people out there who will hurt you.

This isn’t a courtroom drama, where she tells everyone and everything comes out; this is about the woman who has experienced sexual violence who doesn’t say anything. This is really relevant. A lot of women have said to me, after seeing the film, “I had a couple of situations like that.” Which is sad, because they feel like, “Well, them’s the breaks—at least I walked away from it, and now I know better, and I didn’t tell anybody because it’s embarrassing.”

One critic even asked me, “Do you want me to believe that she wouldn’t say anything?” And that’s so often the case, even with a woman who’s smart and outspoken, because she’s the one who has to say what happened and defend herself against people who would say, “Well, what was she wearing?” Listen, I don’t care if we’re married for 20 years and we have 5 kids together; if I say, “No, I don’t want to have sex with you tonight” and you do it anyway, that’s rape, and that is not my fault. I didn’t lead him into it. I’ve done a lot of work with V-Day and Eve Ensler, and the statistics are that one in four women in the U.S. has been or will be raped or molested. So we all know somebody who’s been through it.

But the movie is also about the descent of [my character’s] personality, about her trying to normalize the violence against herself by becoming promiscuous and violent. She goes back to college for her next semester and sees the guy who raped her, and she decides to get revenge on him with her friends. She thinks that becoming violent means taking back her strength, and—well, you can judge for yourself. Some people think this is a wonderful thing that she’s doing—at a few screenings, the audience has been like, “Woo-hoo, she’s getting revenge!” And then they see what that looks like, and they get dead silent again. This isn’t the movie where revenge is really fun and like “kick-ass girl power.” This is the movie that explores the moment afterward, when revenge doesn’t feel as good as she thinks it will. She’s no longer the victim; now she’s a perpetrator. She’s started the cycle all over again. It’s like war—you bomb my country, I bomb yours, and who wins? That’s just more dead people; nothing’s great about that.

It sounds like there’s a parallel between this film and the Quentin Tarantino movie you recently did, Death Proof (half of the double feature Grindhouse), in which a group of women are menaced by a guy and they take their revenge. I’ve heard you describe that movie as a “chick movie.”

Well, obviously, Death Proof isn’t meant to be realistic, it’s a goofy cartoon. It’s an homage to grind-house movies, where women were allowed to do the same things men did in movies—pimping and killing and all that stuff. Those old blaxploitation and grind-house films were the first to let women assume those roles, especially women of color. At the same time, I was talking to Goldie Hawn about it, and she said, “I don’t know who says that just because the women beat up the guy in the end, that makes it empowerment. I don’t need to beat up a man to feel empowered as a woman.” I mean, I said Death Proof was a chick flick because you look at the poster, and it looks like a total gearhead guy movie, but really, the women are in control. As much as it starts off misogynistic, with this creepy guy who’s checking out this group of girls, the girls turn on him. And they take this guy who’s really dangerous and scary, and they turn him into the weepy cowardly lion. It’s meant to make you feel euphoric when you leave. Whereas [Descent] is specifically done to take you on a deeper journey, for you to think seriously about violence and revenge and sexism and racism, about emotional violence and verbal abuse. It’s an upsetting film to watch—like Kids, you walk away horrified. So both Descent and Death Proof are horror films—there’s the parallel.

I read that you asked Tarantino if you could make one minor change to a scene in Death Proof, in which three of you girls leave one of your girlfriends behind in kind of a sketchy situation with a guy who’s leering at her. What was the change you requested, and how did he react?

[laughs] This has turned into this whole thing on the Internet, like, “Rosario’s trying to change a director’s vision, she’s trying to get a rape scene taken out of a movie!” All I said to Quentin was, “This girl’s my friend, and this guy’s clearly sketchy, and I’m just throwing her to the wolves. That doesn’t seem realistic. There’s another car that she could use. Can’t we just symbolically throw her the keys?” And he was like, “No. You’re not thinking about her; you’re just happy that you get to go off with the cool kids.” Because that’s the story we’re telling, and that’s what my character’s about. My character is like the stand-in for Quentin; he wants to hang out with the cool girls. But at least I made my statement, and I got where he was coming from. It’s not a movie about reality. It’s about a girl sliding around on the roof of a car while a guy chases [her and her friends]. It’s not supposed to make you think about rape and reality and all that; that’s not the movie he wanted to make. So I made that movie.

Can you tell me a little about the Lower Eastside Girls Club of New York and how you became involved?

Well, when I was growing up in a squat in that neighborhood, there were two boys’ clubs but no girls’ clubs. And when the boys’ club was asked to integrate with a girls’ club, they declined. So about 10 years ago, a group of mothers started a club for girls in a neighborhood basement. I’ve been involved for the past four years or so, trying to raise money and awareness for them. They have a bakery and café, which employs some of the girls and their mothers. They also have a gallery and a photography program and sewing and dance classes, and they’re affiliated with a group of girls in Chiapas, Mexico, where they go twice a year.

I got involved because my aunt works on the Lower East Side, and I’d meet some of these girls, and they’d say, “Oh, you’re so lucky, you have this incredible life, I’ll never have what you have.” And what can I say? “Sit on your stoop and wait for someone to discover you?” I want them to have every opportunity they can and every good influence—I got them tickets to see [Broadway performer] Sarah Jones, I’m getting [stuntwoman] Zoë Bell to come talk to them—because the dropout rates in that neighborhood are really high and so are the teen-pregnancy rates. My mom got pregnant with me when she was 16, and she wanted me to have as many choices as I could in life, and that’s what I want for these girls.

I don’t lend my name to a lot of things; I don’t sell makeup. If you see me in the press, it’s because I’m promoting a movie. But I want to use my name to promote these girls. We all need a champion, and I want to be theirs. The women who started this have been doing it for so long for no money, and the girls make such great art—their gallery shows and their writing is so inspiring. I’m grateful to be affiliated with them.

You mentioned that you want these girls to have choices. Are you pro-choice?

Well, it’s interesting, because my mom almost aborted me. She was 16, and she was in the abortion clinic, ready to go through with it, and the doctor called her name, and she said she felt something move, and she couldn’t go through with it. And I’m like, “Mom, I was the size of your thumbnail, you probably had gas.” But luckily for me, that was her choice.

For me, it’s about giving people information, regardless of what I believe in. I mean, I change my mind about it. It’s not something I’ve had to deal with personally. But it’s something that I think everyone should have a choice about. I watched my mom and how people treated her differently because she chose to have me so young. And now that my brother and I are successful, people say to her, “Oh, what a great choice you made,” but what about those women [for whom] it didn’t work out that way? I was just in Nicaragua with an organization called Operation USA, doing relief work and delivering medical supplies to one of the main public hospitals in Managua, and [I heard about] a young woman there who’d been raped and became pregnant. She didn’t want to have the kid, but abortion is illegal there, and then when her placenta broke, she couldn’t afford a two-dollar sonogram, and she wound up dying.

So for me, it’s about information. Like with AIDS in Africa—some people there don’t understand what it is, or they think raping younger women will cure it. And now it’s an epidemic, the plague of our time. It’s spreading mostly among young brown women, and these young women don’t always have a lot of choices. And that’s one thing I was always raised with—which is not to say that my family has always loved every choice I’ve made. When I was naked in Alexander or I was cursing in Kids, my grandmother was still supportive of me, even though she’s Catholic. She was like, “Hey, if you can sleep at night, and you’re happy, that’s great. You should enjoy your life, so you can look back on it and not regret the choices you made.” That’s what’s most important. At the end of the day, you have to make choices for yourself. This is the world you live in; what kind of world do you want it to be?

[At the same time] there’s not enough accountability and personal responsibility. We have freedom of speech, we all have MySpace and blogs, we can say whatever we want to say, but what are we saying? I mean, the Internet can be great—that’s why we had millions of people marching against the war in Iraq. That’s why there’s no reason for apathy. In 2006, when I saw the way college kids were mobilizing and marching for immigration reform, I was so happy and amazed. 2006 should be remembered as the year when those kids walked out of class for immigration reform.

Since this is our fashion issue, my last question to you is fashion-related. I read that you’re being styled by [celebrity stylist] Rachel Zoe these days. What’s that like? Is she, like, made out of radiation? It seems as if she causes skinniness in humans.

I don’t think Rachel causes skinniness; I’ve never seen or felt any pressure to be thin coming from her. I’m a busty woman, and she loves that. She says, “Look at you, you’re so lucky.” She makes me feel beautiful, and she’s known for that. She found me this Dolce & Gabbana dress for the opening of Death Proof here at Cannes—a beautiful, heavy, zip-up dress. It weighed about 25 pounds, and it fit perfectly.

It would be great if we could find a bad guy to pin things on and say, “OK, it’s all her fault,” but it’s not that easy. We have to take personal responsibility. People want to say, “Oh, it’s movies” or “Oh, it’s Rachel Zoe’s fault,” but if there’s a girl making herself skinny or sick, then it’s about that girl. And we talk about it like it’s entertainment, which is really belittling. People are persecuting these young girls for making some poor decisions, as young people will do. They’re saying, “What kind of role model are they?” And it’s like, you’re the one making them a role model. They’re just a kid making mistakes, and nobody gives them any kind of break.

You know, I’ve watched those girls, the famous ones, and they’re coddled. Nobody’s honest with them. A friend gave me an article recently about acquired situational narcissism—technically, narcissism is something that happens in childhood, where you miss the transition from infancy, and you don’t like the fact that you go from having your mother take care of everything for you to having to wipe your own butt and feed yourself. It’s like the world revolved around you and suddenly you realize that it doesn’t. But you can become narcissistic later in life—maybe you became famous at 20 for playing basketball, and now everybody treats you differently. And that’s a scary thing. And so people start acting out and thinking they’re untouchable and flirting with disaster, because they’re being told they can do no wrong. And then they become sad and depressed and suicidal. Fame has a lot of aspects that are really abnormal.

It’s interesting living in L.A. and seeing what the image of a beautiful woman is and how people treat themselves—the Latina women dying their hair blond, people throwing up so they can fit into their skinny jeans. But that’s just one part of one percent of the world’s population. You go around the corner and people are thinking about how they need AIDS meds or they need child care, because there are unwanted children being born with no access to health care right here and now. My mom did Thanksgiving dinner in New Orleans last year, and people there still need sheets and underwear. That’s what’s real, and that’s what’s important.

Story by Janice Erlbaum

Photos by Michael Lavine

Styling by Frances Tulk-Hart // Makeup by Steven Arturo // Hair by Luca Blandi

This article originally appeared in BUST’s August/September 2007 issue. Subscribe now.

More from BUST

Rosario Dawson Fights Fast Fashion With Studio 189: Interview

Natasha Lyonne On Fame, Love and Monogamy: From The BUST Archives

Frances McDormand On Aging In Hollywood: From The BUST Archives