Since the 1960s, feminists have been protesting the sexism of beauty pageants. But others have chosen to subvert these competitions from the inside, entering as a form of activism.

On a Saturday morning this past September, Anita Green walked across a stage in a black cocktail dress and pink lipstick to become the first trans woman to compete in the Miss Montana USA pageant — ever.

Already well known in Montana as the state’s first trans delegate, Green entered the pageant, in part, as a political statement. “I don’t want trans people to be afraid to be who they are,” she says of her decision to compete. “Trump has immensely harmed the trans community and instilled fear in us. I want to inspire confidence among trans women to know that they are beautiful.”

By competing, Green sought to boldly claim space for trans women like herself, and to communicate to the world that trans women are here, they are beautiful, and on pageant night, they will be striding proudly into your living room.

It’s easy to see Green’s participation in Miss Montana USA as an isolated courageous act. Perhaps that’s because most feminists are used to thinking of pageants as something to protest against. But the truth is, by competing—even though she knew the deck was stacked against her—Green was taking part in a rich tradition of women using pageants as platforms for political change. To understand her story in context, we have to go back to the middle of the last century—to the height of the American Civil Rights Movement.

Anita Green, the first trans woman to compete in the Miss Montana USA Pageant, 2017 (Courtesy of Anita Green)

Anita Green, the first trans woman to compete in the Miss Montana USA Pageant, 2017 (Courtesy of Anita Green)

THE FIGHT TO DESEGREGATE BEAUTY PAGEANTS

By the late 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement had made its mark on American society. The decade had been rocked by bus boycotts, freedom rides, lunch-counter sit-ins, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and Brown v. Board of Education—all of which seemed to be reconfiguring the fabric of the country.

Against this political backdrop, the Atlantic City chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began to push for integration of Miss America. The pageant—a sunny, touristy affair held near the boardwalk each year in late summer—was open exclusively to white competitors. In a now infamous bylaw, racial exclusivity was codified: “Contestants must be in good health and of the white race.”

The Miss America contestants of 1953. (Library of Congress)

The Miss America contestants of 1953. (Library of Congress)

To many members of the black community in Atlantic City, the arrival of the racially exclusive event into their town each year was yet another reminder of the segregation they faced on a daily basis.

Several NAACP leaders were outspoken against the pageant. Philadelphia-based NAACP official Philip Savage suggested a boycott of all sponsors of the Miss America Pageant, saying, “It is time for Miss America to be Miss America and not Miss White America.” Edgar Harris, the president of the Atlantic City chapter of the NAACP, was quoted as saying, “We should not be calling it the Miss America Pageant because it won’t be that until we find some negroes representing some of these United States.”

In 1968, the situation reached a tipping point. Miss America president Adrian Phillips, under pressure from both the NAACP and a cultural shift toward integration, agreed to remove racial exclusivity from the pageant rules; for the first time in the contest’s 47-year history, black women would be allowed to participate.

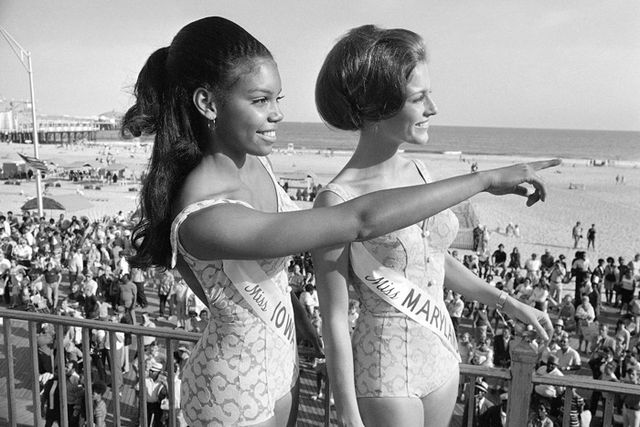

Miss Iowa, Cheryl Adrienne Brown, the first African American to reach the finals in the Miss America Pageant, on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, NJ, in 1970 with Miss Maryland, Sharon Ann Cannon (AP Photo)

Miss Iowa, Cheryl Adrienne Brown, the first African American to reach the finals in the Miss America Pageant, on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, NJ, in 1970 with Miss Maryland, Sharon Ann Cannon (AP Photo)

A PLATFORM FOR POSITIVE IMAGING

Perhaps from our vantage point in history, it is not immediately clear why beauty pageant integration was a politically meaningful strategy. But it is important not to underestimate the power of images in the cultural imagination—and during this era, it was difficult to imagine a more potent venue for positive imaging than Miss America. Americans had been glued to their television sets every year on pageant night since the contest was first televised in 1954 after 33 years as a legendary live attraction in Atlantic City, NJ.

From the perspective of civil rights activists who sought pageant integration, beauty contests represented a unique opportunity to broadcast positive images of black women into the collective consciousness. For the same reason, efforts had also been made to increase black representation in the modeling industry. In 1947, The Amsterdam News in New York City published a letter to the editor that read, “This is not just a question of…getting modeling jobs open to negro women in agencies that discriminate at present. This can be the beginning of getting pictures of negroes in our magazines…other than that of maids, butlers, or mammies.”

A vintage Atlantic City postcard

A vintage Atlantic City postcard

Indeed, Miss America seemed to be a powerful platform from which to broadcast a vision of black womanhood that diverged sharply from “maids, butlers, or mammies.” In fact, five times throughout the 1960s, the Miss America Pageant was the highest-rated television show of the year. It was the most glamorous program on TV, reaching almost mythological heights in the cultural imagination. Therefore, in looking to the Miss America Pageant, the NAACP Atlantic City chapter recognized a prime opportunity to help shape the narratives of both blackness and all-American beauty.

Two years after black women were deemed eligible to compete, Cheryl Brown became the first black woman to win a state competition and went on to compete in Miss America as Miss Iowa in 1970. Many civil rights activists rejoiced. After years of encouraging black women to enter traditionally all-white beauty contests, at last, that racial boundary had been crossed.

The first black Miss America, Vanessa Williams, in 1983 {Ebony Magazine)

The first black Miss America, Vanessa Williams, in 1983 {Ebony Magazine)

BEAT THEM OR JOIN THEM?

Certainly not everyone saw Miss America as a worthwhile platform. In 1968, the same year that black women won the right to be included in the pageant, a group of predominantly white feminists fought to rid the culture of the event altogether. Organized by the activist group New York Radical Women, the No More Miss America protest called on feminists to help “reclaim ourselves for ourselves,” and identified 10 main ideas the demonstration would be addressing, including “the degrading mindless-boob-girlie symbol,” “racism with roses,” and “the unbeatable Madonna-whore combination.” The protest was attended by over 400 feminists who proclaimed with chants and signs that the sexist beauty standards glorified by Miss America oppressed women. Gathered outside the pageant on the Atlantic City Boardwalk, they cheered while key organizer Robin Morgan tossed a collection of symbolic feminine products, including cookware, false eyelashes, and mops, into a “freedom trashcan.” Later that evening, demonstrators also successfully unfurled a large banner reading “Women’s Liberation” inside the contest hall. The event drew worldwide media attention and brought the second wave feminist movement into households everywhere.

The No More Miss America protest (Aliz Shulman holding poster), Atlantic City, 1968 (COPYRIGHT ALIX KATES SHULMAN; USED WITH PERMISSION)

The No More Miss America protest (Aliz Shulman holding poster), Atlantic City, 1968 (COPYRIGHT ALIX KATES SHULMAN; USED WITH PERMISSION)

White feminists weren’t alone in their disdain for Miss America. There were also plenty of black civil rights activists who did not see the pageant as a suitable medium for their message. While entering women of color into traditionally all-white pageants seemed like a worthy goal for some working to advance racial equality, the Eurocentric beauty standards of such contests usually barred participation by all but the lightest-skinned black women. And many activists responded to this shortcoming of integration as the Civil Rights Movement wore on. For example, the Black Power Movement, which grew out of the Civil Rights Movement, rejected integration as a short-term goal. Similarly, pageant integration was certainly not a priority for the Black is Beautiful Movement, which emerged from a push to reject the internalization of Eurocentric beauty standards. Alongside the Black Power Movement, Black is Beautiful asserted that black skin and hair textures should be idealized and that the worship of Eurocentric beauty standards was evidence of continued oppression.

Dr. Blain Roberts, professor at Fresno State and author of Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the Twentieth-Century South, gave voice to these hesitations around the efficacy of beauty pageant integration. “Some historians would say that a black woman, in order to be successful in an all-white beauty pageant in the 1960s, had to engage in a type of racial passing,” she writes. “This revealed its limitation as a strategy: How much can you change conceptions of beauty when the standards are white-based?

The very first Miss America, Margaret Gorman in 1921 (Wikimedia Commons)

The very first Miss America, Margaret Gorman in 1921 (Wikimedia Commons)

ENTER: THE MOVEMENT FOR TRANS INCLUSION

In an era when trans visibility has reached unprecedented heights, there remains the question of whether beauty pageants are indeed an appropriate venue for trans advancement. In entering mainstream beauty pageants, trans contestants like Anita Green face similar barriers: the heteronormative ideals celebrated by mainstream beauty pageants are sure to reward only those trans women who can “pass” enough to be palatable for a mass audience.

And even when a contestant can pass, that does not automatically free her from controversy. In 2012, Jenna Talackova, a trans beauty contestant in the Miss Universe Canada pageant, strode into the international spotlight when news broke of her disqualification from the contest based on a rule stating contestants must be “naturally born female.” She was later allowed to re-enter after the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD)—in a move analogous to the NAACP’s 1968 action on behalf of black women—intervened, negotiating a rule change. She earned the title of Miss Congeniality and made it to the top 12 before being eliminated.

Jenna Talackova was disqualified from the Miss Universe Canada pageant in 2012 for being trans. She was later allowed to re-enter (Photo: ANNIE JACKSON)

Jenna Talackova was disqualified from the Miss Universe Canada pageant in 2012 for being trans. She was later allowed to re-enter (Photo: ANNIE JACKSON)

The following year, another trans woman, Kylan Arianna Wenzel, competed in the Miss California USA Pageant, garnering national and international attention before being eliminated. And four years and one Trump election later, Green became the third trans woman to participate in a mainstream beauty pageant.

She was aware that beauty pageants tended to reward heteronormative standards of beauty, but hoped to challenge this dynamic. “I know I don’t have the stereotypical beauty that most pageant contestants have,” she says. “I know that I have more masculine features. But that’s partially why I chose to compete. I wanted trans women to know that they are beautiful—whether or not they ‘pass.’”

It seems clear that beauty pageants will continue to reward women, regardless of birth gender assignment or racial background, who cleave to heteronormative, Eurocentric ideals of beauty. There is, however, some disagreement about whether this is a tolerable sacrifice to make in the struggle for greater trans representation.

EXPANDING REPRESENTATION IN BEAUTY PAGEANTS

Trying to gain access into the cis, white pageant world when you are not one or both of those things continues to be a thorny proposition. But there will always be those who believe that representation of any members of a disenfranchised group is consequential for all members of that group.

Perhaps, with an initial barrier broken, the way is paved for greater diversity in beauty pageants. For example, it is interesting to note that while the first black women who won Miss America and Miss USA crowns tended to be lighter-skinned—like the first black Miss America, Vanessa Williams, crowned in 1983—ensuing years saw the crowning of darker-skinned women like Deshauna Barber (the ninth black winner of Miss USA) and Marjorie Judith Vincent (the fourth black winner of Miss America).

Miss USA 2017, Deshauna Barber(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Miss USA 2017, Deshauna Barber(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Entry as a controversial or boundary-breaking contestant isn’t the only way women are using pageants as sites of protest. For instance, in 2017, during the Miss Perú pageant, contestants drew attention to the extreme levels of violence against women in their country by hijacking the portion of the evening in which they would usually repeat their body measurements to instead give statistics about femicide.

Regardless of one’s platform, it would be wise not to overlook the significance of beauty pageants in the cultural imagination. Gone are the days when Miss America was the most highly anticipated television event of the year, but the beauty pageant is still a surprisingly compelling symbol. Evidence of the importance many still place on Miss America as a representative of national identity and belonging can be found in the online outrage generated by the crowning of Nina Davuluri, a daughter of immigrants from India, in 2013. Online commenters raged about the crowning of a “foreigner” (though Davuluri is an American citizen) and referred to her, alternatively, as Miss 7/11 or Miss 9/11. The naming of a first-generation American as Miss America seemed to threaten many people’s internally held norms regarding race and national identity, and the backlash was intense.

Miss America 2014, Nina Davuluri, the first woman of Indian descent to win the pageant (Photo: Kevin Dooley)

Miss America 2014, Nina Davuluri, the first woman of Indian descent to win the pageant (Photo: Kevin Dooley)

It seems clear that this outrage points to the tremendous power of representation, which is able not only to reflect cultural understandings, but also to shape them. Would her victory have been a source of so much outrage if it hadn’t been indicative of the changing conception of what a beautiful, American woman looks like? Could a transgender Miss America or Miss USA, in the same way, help shape our cultural understanding?

SO, WHAT?

A recent study out of the University of Southern California found that trans representation in media is linked to greater empathy and more progressive political views among viewers. In an era when violence against trans women is mounting into a public health crisis, we should not be too quick to cast aside studies like these. Pageants, with their wide, national viewership, are prime spaces for this type of beneficial exposure.

Of course, winning beauty pageants cannot be the only route toward wider social acceptance. We must also seek advancements such as trans representation among elected officials—as we saw this recent Election Day when trans women Danica Roem and Andrea Jenkins won their bids for public office.

But who knows? Perhaps a pageant enthusiast who sees Anita Green, or a woman like her, crossing the stage in an elegant evening gown this year will think of her the next time a bathroom bill appears on a ballot at her local voting booth. Culture changes both quickly and slowly, and you never know what factors will combine to create a watershed moment.

By Liz Ellis Mayes

Opener Photo: AP Photo

This article originally appeared in the February/March 2018 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

Miss Teen USA Takes One Small Step Toward Feminism

When We Discuss The Glass Ceiling, Why Don’t We Mention The Costs Of Sexual Assault?