It’s not easy dealing with online trolls or arguing with our friends and family about social issues. Feminists often take on the burden of emotional labor, which author Gemma Hartley defines as “emotion management and life management combined… the unpaid, invisible work we do to keep those around us comfortable and happy.” Just as workers are expected to control their emotions during interactions with difficult customers, the same is expected in our intimate relationships.

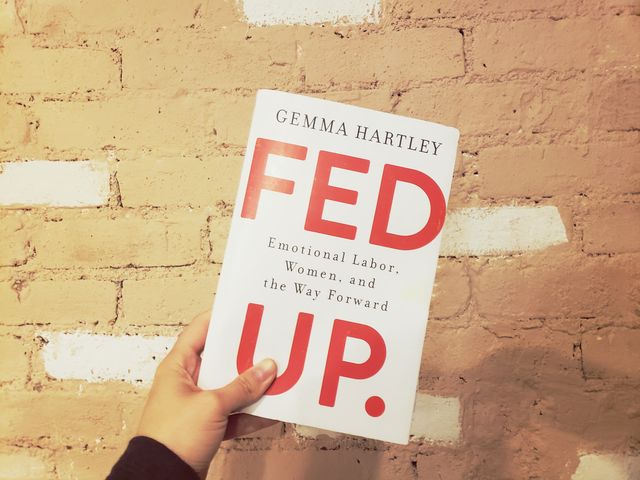

As advocates for gender equality, we are constantly pulled between teaching our partners, friends, and families, while also accepting their not-so-feminist attitudes. Hartley’s Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way Forward speaks to this tension building in the private space of her house. Behind closed doors, gender equality is not as prevalent as she had hoped for.

Hartley gained notoriety when her Harper’s Bazaar article “Women Aren’t Nags—We’re Just Fed Up” went viral last year. The article spoke to the many women who have “leaned in,” balancing having kids and working their day jobs. However, Hartley shares a harsh realization that the “having it all” mantra women like Sheryl Sandberg work to live up to is clearly deceptive in a world where women’s male partners still have a patriarchal mindset.

Instead of “having it all,” Hartley has mainly maintained it all, that is, by cleaning up after her husband and kids while also working her day job. The virality of Hartley’s Harper’s Bazaar article inspired her to write a book of the same caliber. Except this time, she left no mercy in detailing the extent of what she would have to go through to achieve a gender equal relationship in her household.

Hartley shares that her husband is prone to exhibiting what I like to call “household microaggressions.” She understands that he has been conditioned to think the way he does. That his mindset is just an offset of toxic masculinity. But while fixating between understanding him and changing his attitude, Hartley shares how unhappy she’s grown to be:

I am like a woman possessed. I get angry that Rob is sitting on the couch not noticing things like the dusty floorboards or a few small specks of toothpaste on the bathroom mirror […] I’m angry because he is not only caught up in the minutiae, but because I cannot seem to free myself from it even when I want to.

Hartley shapes our knowledge of her situation by unveiling the raw communication issues between her and her husband. She recounts numerous conversations—really arguments—about how they share household chores. Hartley’s arguments, however, are powerless, and she shares her hopeless inner dialogue. In an exhausting act of love for her husband and her relationship, she constantly patrols her emotions when asking him to do household chores:

When I try to explain emotional labor to my husband, it sounds to him like I’m saying, ‘You don’t care at all.’ He hears that I don’t appreciate the work he puts in. But his response ignores the extensive emotional labor that goes into the way I live my life […] The emotional labor of the conversation becomes too much for me, so I instead talk to other women who will understand.

Hartley has unfolded a sad truth: she has found herself in a heteronormative relationship where she has to “tiptoe” around her partner’s male-centered ideas of household chores. Her debut book is a confession and an apology to those who are labelled as nags. She is allowing herself to unravel her anger towards her overused emotional labor. And what she finds is that it’s an enormous, silent burden still sitting on our shoulders as feminists.

Hartley is not only genuinely stating her role as the sole do-er in her household (the one who remembers her husband’s family members’ birthdays, to take out the trash, to clean up after her children), she is also profusely apologizing to herself that she didn’t catch this behavior in her husband sooner. If she had, would she have committed to this relationship? I often asked myself that while reading, and the question is hidden between her sentences.

Hartley’s book shares a keen sociological insight women need to decipher our relationships. Fed Up is intimate, pervasive, and unapologetic. It’s a successful memoir on how to thwart toxic masculinity in its tracks—starting with our partners.

Hartley’s concerns, however, are not trailblazing. Women’s emotional labor has been a constant concern in feminism. Take the bone-chilling, 126-year-old short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, for example. “The Yellow Wallpaper” tells the story of a woman descending into madness because of the domestic role she was forced into. In the late 1960s through early 1980s, feminist scholars contributed to a growing body of knowledge surrounding the politics of female emotional labor by sharing their stories of oppression. This became feminist standpoint theory, emerging in the 1970s with scholars such as Dorothy Smith, Nancy Hartsock, Hilary Rose, Sandra Harding, Patricia Hill Collins, Alison Jaggar, and Donna Haraway. They analyzed the dynamics of power within the patriarchal structure, taking note of women’s injustices when it comes to unpaid labor and the emotional burden of managing a household. In 1979, Audre Lorde exposed the intersections behind unpaid labor as she remarked on how women of color were now the ones to clean houses and tend to children, while white women involved in feminist circles simply spoke of their own oppression.

Hartley extends the conversation of emotional labor to privileged women who seem to “have it all.” The women we seem to demean and love simultaneously for their privilege. The kind of women that seem to embrace the popular matriarchal encouragement narrative by shouting empowerment from the rooftop, such as the Instagram mommies and fitness models of the world. But hidden behind this privilege is acceptance of the toxic masculinity that Hartley exposes when the facade is stripped away in the private sphere of the household.

Emotional labor is a taboo subject among feminists dating cishet men when we let our partners get away with oppressive attitudes. Our romantic partners may not always understand the stark boundaries of gendered household roles, and the truth to this fact is that we even applaud the minsule achievements from our partners, like washing the dishes or vacuuming. “We must start with our children, our partners, ourselves to create change,” Hartley writes. Emotional labor is “a conversation we must invite men into,” but we must also “disrupt the cycle” of “tiptoeing around men’s feelings.”

Hartley writes that when we’re faced with this situation, we can first learn to cope by speaking to others about our aggression, whether it be our friends, mothers, or therapists, because our partners have not been conditioned to care. However, she is a clear advocate for addressing the situation by finding out how to shut down these toxic masculine attitudes while also saving her marriage. “The truth is that I don’t need help – I need full partnership,” she writes. Her insistence towards working through theses barriers through arguing, conversing, and working alongside her partner is enough to be considered a win. But, she reveals, it’s exhausting. She insists that the future of feminism clearly starts with a gender-equal household.

Hartley’s stance on emotional labor is defined extremely clearly for those who want to be in a relationship: the traditions of patriarchy don’t work for us anymore. We’re tired. And we’re fed up.

By Alissa Muradliyan Medina

This post originally appeared on Fembot.com and is reprinted here with permission.

Top photo: Pixabay

More from BUST

“The Second Shelf” Is Fighting Literary Sexism

“My Sister, The Serial Killer” Is A Dark, Funny Novel With A Lot To Say

Michelle Obama Emphasizes The Importance Of Women’s Stories While Kicking Off Book Tour In Chicago