Leaping for Love

Every four years, an extra day, February 29, is added to Western calendars in order to keep them roughly in synch with Earth’s transit around the Sun. And for centuries, these so-called “leap year” days have been a time when women were allowed to put aside conventional etiquette and propose marriage to men.

The roots of the leap year proposal tradition are murky. Some point to St. Brigid of Kildare, whose complaints about men’s sluggishness to propose circa 500 AD led St. Patrick to grant women the right to do so every leap year day. Others point to a Scottish law allegedly passed during the reign of an unhappily single Queen Margaret in 1288 (when the historical queen was only about five years old).

Of course, all the stories have at their base an assumption of cisgendered heterosexuality and patriarchal authority. Prior to the 1970s or so, middle and upper class wives were not expected to work outside the home. A man proposed marriage when he had the economic wherewithal to provide for a home and family. Waiting for a man to propose appealed to his masculinity (so the reasoning went) and was a sign of a woman’s feminine submissiveness.

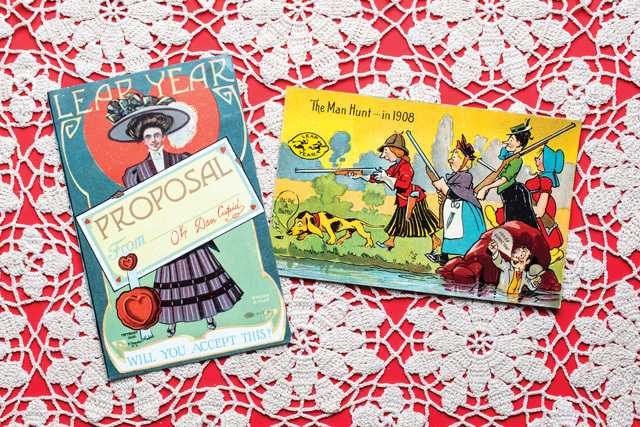

Commercially printed leap year cards were available for purchase beginning towards the end of the 19th century. A newspaper noted in 1876 that girls in Connecticut were sending out a “leap-year card with the inscription, ‘May I C U home, to-night?’” to boys of their acquaintance before a party.

The leap year proposal was also the butt of much humor. Women who popped the question were portrayed as desperate spinsters out to divest wary males of their freedom. Because all the presumably “good” men had already proposed to and married the women of their choice, the only bachelors left were puny misfits, who prized their freedom over wedded “bliss.” A batch of brightly printed postcards from 1908 showed wily old maids tracking men like animals, or baiting traps with money to lure in unsuspecting fortune hunters. Other cards took a more subtle approach, suggesting to male recipients that now was a good time for them to step up and propose. “Why Don’t You Try” was the message of an acrostic verse about “the joys of wedded life” that appeared on one of these cards.

Another turn-of-the-20th-century card came with a pin reading “Speak dear, this is leap year.” A century later, the message here may be a bit too subtle: Did a woman send it to a man, prodding him to propose? Or was a man supposed to send it to a woman, letting her know it was OK to pop the question?

Either way, women who “openly [sought] admiration or affection” from men were “unworthy,” according to a Ladies Home Journal advice columnist in 1908. The tradition of the leap year proposal was “nothing but a joke, and should not be taken seriously,” the author warned. “Men desire to be the pursuers, not the pursued.”

Photographed by Amy Elizabeth

This article appeared in the May/June 2019 issue of BUST. Subscribe HERE!

More From BUST

A Comprehensive History Of Women’s Underwear

War Letters Teach Us More About History Than Any Textbook Can

This Designer Mined Her Heritage To Make Modern, Meaningful Clothing