The Contagious Diseases Act (here by shortened to the CD Act, because as important as it is…it’s one hell of a mouthful) came about in part due to the rapid rise of prostitution in Victorian England. Prostitution was the fourth largest occupation for working women* and it grew along with the boom of the British Empire.

This bombastic empire expansion led to thriving new trading routes and soon, British sailors were bringing home ships full of tea, textiles, and venereal disease. Yep, you have to take the bad with the good, and one of the prices for this exciting new empire? An exciting new STI! Sailors picked up VD from their travels and then spread it back in Britain when they arrived home after a long time at sea and in need of some company…

The disease spread quickly and became an epidemic. Parliament needed to do something to control the situation and fast! So in 1864 they covertly passed the Contagious Disease Bill.

The bill allowed for any person suspected of being a “common prostitute” to be forced into submitting to an internal genital exam by a male doctor.

Here’s the thing: the law only applied to women.

The examination was humiliating and painful. It would later be described as ‘surgical rape.’ Countless female sex workers found themselves subject to this ordeal.

Even worse, there didn’t need to be any evidence for a woman to be accused and therefore internally examined. This resulted in many women who were not sex workers having to undergo the examination. With both the accusation and their examination now public knowledge, these women found their reputations destroyed – they became “ruined women,” and their chances for a hopeful future were vastly diminished.

Parliament renewed the CD Act in 1866 and again in 1869, increasing the penalty for not submitting to a genital exam to 3-6 months in prison with the possibility of hard labor. This was later raised to 6-9 months to help the women ‘become clean.’

Over the course of the Act’s frequent revisions, hardly any of the public knew about it – though it affected 50% of the population, it remained a secret. That was all about to change.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme

Elizabeth Wolstenholme

In 1869, a meeting about the bill was held at Bristol’s Royal Hotel. At this meeting was women’s suffrage campaigner Elizabeth Wolstenholme. She was shocked to hear about the CD Act, which had now been in effect for almost 5 years.

Elizabeth saw the CD Act as a violation of women’s rights and made it her mission to raise public awareness. After leaving the meeting Elizabeth contacted her friend Josephine Butler and asked for her help. Butler was a social reformer and women’s rights campaigner who had previous experience working with and campaigning for the rights of women working as prostitutes.

Josephine Butler

Josephine Butler

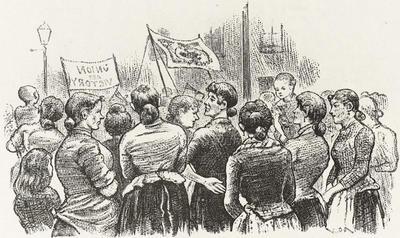

Butler and Wolstenholme toured the country giving speeches about the Act. To say this is shocking would be a huge understatement: a woman talking openly in public about sex in the Victorian era was shocking and seen as deeply concerning. Yet the speeches worked. The women sparked something and people started talking, and when people started talking, they became outraged.

Soon Butler and Wolstenholme formed the Ladies’ National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act (LNA for short) and in doing so arguably became two of the first publicly known feminists. Though women before them had previously fought against slavery and war, this was the first time in British history that women were fighting for all women’s rights and women’s sexual rights at that.

(pic)

In 1869, the fledgling LNA published a petition with 124 signatures calling for a repeal of the CD Act. Two years later in 1871, they produced another petition calling for the repeal – when it was handed in to the House of Commons, it had to be laid on the floor as there was not a table that was large enough to hold it. Groundbreaking doesn’t even cover it.

The LNA worked tirelessly over many years to end the CD Act, but that wasn’t all Butler and Wolstenholme did – in fact, from the start of the Contagious Diseases Act to its end, both women did an extraordinary amount:

IN 1886, THE CONTAGIOUS DISEASES ACT IS FINALLY REPEALED.

*Though a reliable estimate of the actual amount of women working in this field does not exist, we can see that throughout the 1840s and ’50s the number of women working in prostitution was rapidly growing.

This article originally appeared on F Yeah History and is reprinted here with permission.

More from BUST

Sex Work In New York State Might Be Decriminalized—Here’s What You Should Know

In “Blowin’ Up,” Women Work To Change The Way We Prosecute Arrested Sex Workers

What It’s Like To Take An At-Home STD Test