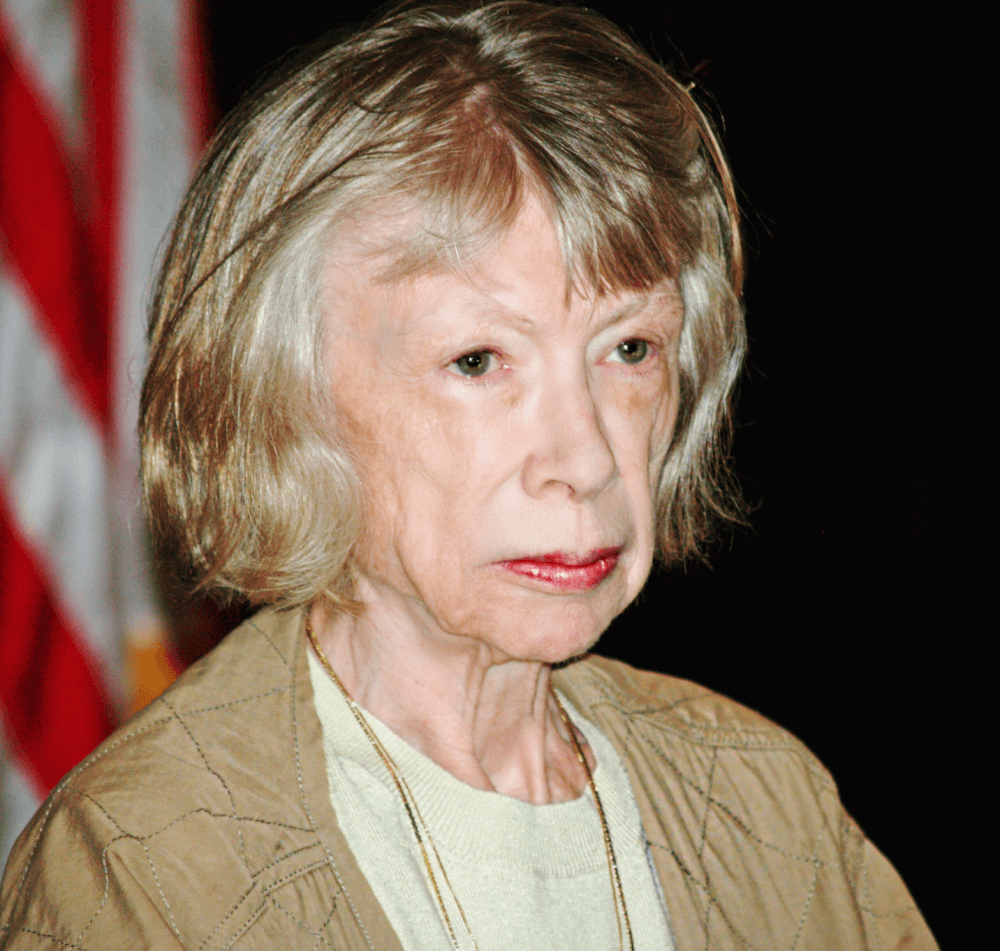

When Joan Didion died on December 23, 2021, there was an outpouring of national grief. Didion was a pioneer of ‘new journalism’ – long form reporting marked by the writer’s point of view. She was honored with The National Medal of Arts from Obama and a PEN USA lifetime achievement award in 2013. She left us with sixteen books, seven films, a play, and at least two generations of writers influenced by her unique style and calculated craft.

As a female writer and a California native myself, obsessing over Didion is practically my birthright. Since her arrival in Los Angeles in 1964, Didion has become a literary icon. With the rise of social media, her following has molded into a cult of internet savvy female followers. Snapshots of her books placed strategically on sleek coffee tables, or cracked open by poolsides flood Instagram and Twitter feeds across the globe. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live”, the first sentence in Didion’s 1979 essay collection, The White Album, has become a hashtag.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

— Joan Didion pic.twitter.com/LhV0bRDSGK

— Farhan Siraj Ahmed (@farhanahmed) January 4, 2022

While the making of Didion into some Instagrammable avatar strikes me as reductionist, she defined the way that people thought about culture, society, and themselves through her writing. Her 2005 memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, which chronicled the months of grief after the sudden death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, catapulted her popularity and profound influence. She showed generations of female writers what was possible – including myself.

I was gifted Didion’s 1968 collection of essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem – a precise rumination on her experiences in California, as a hand-me-down from my older sister on my thirteenth birthday. I remember sitting on the hot pavement on a sweltering July day in the San Fernando Valley. My parents had just separated, and my mom had just been diagnosed with cancer. It was a tough time filled with heavy emotions, and as a teenage girl I didn’t have the words to express any of it.

I grew up in a family of submissive women and dominant, opinionated men. The values of ‘1950s housewife’ had been passed down for generations. I watched the women in my family repress, shrink, and stay small. When my mom was upset with my father or her father, she’d anxiously tap her heeled boot by the kitchen counter – click, click, click – as the men boisterously and carelessly spoke over her. Like many young women, I’d already begun to internalize the message that as a woman you should take up as little space as possible.

Joan Didion was the first woman who shattered that stereotype for me. Her writing took up space – it was biting, declarative, and memorable.

At school, my male friends casually and confidently stated their opinions as facts. In comparison, my opinions always felt like lingering questions. Did I really think Holden Caulfield from Catcher in the Rye was a self-pitying narcissist? Should I say that I think that Jordan Baker should be the focus in the Great Gatsby out loud?

As I read more Didion and absorbed her self-assured voice, I began to realize that I could have a voice like that, too. Didion not only had a voice, she made an art out of having a voice. She used meticulous wording and innovative sentence structures to convey the boldest of points that prompted people to really look inwards.

In one of her first essays that I read, On Self-Respect, she writes “There is a common superstition that ‘self-respect’ is a kind of charm against snakes, something that keeps those who have it locked in some unblighted Eden, out of strange beds, ambivalent conversations, and trouble in general. It does not at all. It has nothing to do with the face of things, but concerns instead a separate peace, a private reconciliation.” I remember frantically scribbling in the margins of the book the first time that I read this sentence. Didion was always concerned with getting to the core questions of what it means to be human. Her language was so clear and precise. She questioned who and what she wanted to, regardless of how it might make her readers feel.

Her work often contradicted popular opinion and pointed out something truly eye-opening and original. In 1979, she wrote a scathing critique of Woody Allen’s beloved films, Manhattan and Annie Hall, in the New York Review of Books, that suggested that his characters were simple-minded and unrealistic.

Like many twentieth century women, Didion did not explicitly identify as a feminist. She openly criticized much of second-wave feminism. Yet, I credit her with gifting this all-encompassing tenant of feminism to so many— empowering those on the margins to have as loud a voice as anyone in the room.

Didion’s essay ‘On Keeping A Notebook’ convinced me to start writing down my thoughts and opinions. For me, this exercise single-handedly changed the way I thought about my voice in the world. Writing things down helped me to solidify my opinions in a world that taught me to constantly question myself.

Didion explains that for her, keeping a notebook was also about figuring out what she thought by writing it down, but it was more so about remembering past versions of herself. She says that even though her notebooks were filled with seemingly meaningless observations of her surroundings (“Dirty crepe-de-chine wrapper, hotel bar, Monday morning”), they brought her back to how it felt to be her at a particular moment in time: “My stake is always, of course, in the unmentioned girl in the plaid silk dress. Remember what it was to be me: that is the point.”

After Didion’s passing, I searched for the first purple moleskin I bought myself after reading her essay. I wanted to remember who I was when I first encountered Joan Didion. I took a breath and flipped it open. In tight, slanted blue ink there was the first note I’d written: “Mr. P’s bulging, green eyes. Uncrustable wrapper on the back desk. The faint smell of a heater running in the classroom. Eighth Grade, Science class, December, 2010, Wednesday, mid-morning.”

Didion was right. I was immediately transported back to that time. I was that eighth grade girl again – pink braces, long, tangled hair. She was so eager to please, so unsure … but with a pen in hand and a copy of Didion by her side, she was beginning to find her voice.

Header image: David Shankbone via Creative Commons

Middle image: Christopher Michel via Creative Commons