The year is 2004 and I am nine years old. George W. Bush is (still) president, Janet Jackson is the talk of the country over a notorious wardrobe malfunction, and Friends has everyone weeping over the last episode of the series. I’m not really a preteen and I still have the length of high school’s entirety before I become an official teenager. But this is the year of Mean Girls, and you bet that my wannabe teenybopper ass is watching. I also have glasses, buck teeth that stick out despite having braces and wearing a retainer, and I’m in Battle of the Books, where I read certain books, then compete with other students to see who knows the content best.

The film, written by the incredible Tina Fey, is set near my hometown in Evanston, Illinois. We all know the plotline, because chances are, it’s one of your favorite movies. And what a great movie it is! Lindsay Lohan assimilates to a new high school with a social hierarchy topped by “The Plastics,” and infiltrates their group just to expose them. It’s not the classic plotline for a teen movie (more on that later), but after absorbing this art, I start to accept that this is how high school works: the girls who are popular, beautiful, and cuffed to boys are the only ones worthy of attention—or, in Hollywood’s case, storylines.

Let’s be real — if the script was about Lindsay Lohan’s character being a cookie-cutter girl trying to make it in high school with her wholesome friends, it would be boring. There would be no tension, no drama, and nothing at stake. The movie, like so many teen movies, has to be watchable, so it has to be relatable, or at least desirable. It had so much of an effect on me that my friends and I used my family’s video camera to film us acting out the movie. To honor my namesake, I played Gretchen Weiners, even though I couldn’t really relate to her, or any of the other Plastics, for that matter.

As I got older, I started to consume these teen cult movies like I ate peanut butter chip sandwiches (I ate these everyday for lunch, just to get an idea). It wasn’t until about 20 years after these movies came out, I started to examine them and notice the effect it had on my, and I’m sure so many others’, self-esteem and worth as a teenager.

1999 was the year teen movies exploded at the box office: Never Been Kissed, She’s All That, Jawbreaker, 10 Things I Hate About You, American Pie, and Drive Me Crazy all came out the same year. I was only four years old when they came out, but I caught up on them in the coming years. I, like Josie Gellar in Never Been Kissed, wanted to be a journalist. I, like Kat Stratford in 10 Things, loved to read voraciously instead of hang out with friends at times. I, like Michelle Flaherty in American Pie, played a woodwind in the school band. These were all characters I had things in common with but could never really identify with. As I reflect on these movies 20 years after their release date, I have some things to note. And if you don’t want me to ruin these nostalgic favEs for you, I suggest you exit out of your browser right now.

Rewatching these films in 2019 is a conundrum. The nostalgia is alive and well, and I can’t help but admire the fashion, the music, and the idea of this “simpler” time so many millennials think back fondly on. I start out with Never Been Kissed, and in my eyes, Drew Barrymore can do no wrong. And she still can’t! But I can’t help but notice the stereotypes it perpetuates for intelligent, sometimes strange, and always sweet young women in society.

The first recurring teen movie plot hole: why is the protagonist written off as uncool and “nerdy” for enjoying extracurriculars like the math team? In Never Been Kissed, when Drew Barrymore’s character goes undercover as a high school student, she’s elated when asked if she would like to be on “The Denominators,” the school’s math team; this is also the case for Cady Heron, Lindsay Lohan’s character in Mean Girls. Personally, I was never good at math, but I never looked at the subject as something that “uncool” people were involved with. If anything, I was envious they were fluent in the numbers language that I couldn’t speak. And while revisiting these classic “chick flicks,” I couldn’t help but think, could this be a reason so few young girls are in STEM?

According to the National Girls Collaborative Project, women remain underrepresented in the science and engineering workforce, although to a lesser degree than in the past, with the greatest disparities occurring in engineering, computer science, and the physical sciences. While women receive over half of bachelor’s degrees awarded in the biological sciences, they receive far fewer in the computer sciences (17.9%), engineering (19.3%), physical sciences (39%) and mathematics (43.1%). These numbers are even statistically lower for women of color.

In Never Been Kissed, the most popular guy, who is actually named “Guy,” says to Drew Barrymore’s “nerdy” best friend/fellow math team member, “Go home and fickle around with your calculator.” How is that an insult? But I’ve seen similar themes in movies released the same year.

To probably many nostalgic viewers’ dismay (like my editor), I cringe thinking about the plotline and writing in She’s All That. In a scene where Zach Siler (Freddie Prinze Jr.) and friends have a beach outing, where loser art geek Laney Boggs (Rachael Leigh Cook) accompanies them, she’s susceptible to bullying. Zach’s best bro, Dean, played by the late Paul Walker, says to Zach in reference to Laney as she’s undressing into a modest one-piece, “Check out the bobos on superfreak! She almost looks normal.” However, her attire in the movie is completely normal, if not on brand for the ’90s — flannel shirts, somewhat baggy overalls, and large glasses.

While I was looking at clips on YouTube of the film, I revisited the satirical take on these teen movies, coincidentally titled Not Another Teen Movie. During one scene, Chris Evans, who is supposed to be imitating Prinze’s character, takes a walk around the quad, looking at fellow female classmates because “given the right look, the right boyfriend, anyone can be this year’s prom queen.”

“What about her?” Evans says, pointing to a girl with a hunchback.

“Way too easy,” his jock friend says.

The camera shifts on an albino girl, playing acoustic guitar. “Any girl with a guitar is hot,” the jock friend says.

“I’m looking for somebody who’s really messed up,” the friend continues. “I’m talking about a real shit bomb.” Cue the actress who is supposed to be emulating Laney, who struts up the stairs in a ponytail, glasses, and overalls.

“No, no, no. Anyone but her! Not Janey Briggs. Guys, she’s got glasses and a ponytail. Look at that, she’s got paint on her overalls, what is that?” It’s funny because it’s true.

I don’t want to be that person who digs deep and tries to find flaws in parts of popular culture so many look back fondly on. But I can’t help but think if I’m doing my younger self a disservice if I don’t consider how these toxic storylines, relationships, and themes affected my coming of age, and my idea of what and how adolescence was supposed to be.

Let’s take it back to The Breakfast Club, which pains me because John Hughes is one of my favorites (albeit I heard he was a dick IRL, and perhaps was the original dude who may have started these high school girl stereotypes). In a study about female representation in teen films, author Maillim Santiago writes, “The Breakfast Club is probably the most progressive of the teen narratives in Hughes’ films. Nevertheless, a couple plot issues do set it back: 1. All of the women find their conclusion with a male figure; 2. None of the female characters have a narrative exploring their independence whereas at least one of the male characters does in the film.” Can we also just make a quick note about how adorable Anthony Michael Hall ends up with no one, while sad boy criminal Judd Nelson and boring jock Emilio Estevez exit the movie with their female counterparts? I know the movie is with five people, so sure, one gets left out, and of course, it’s the nerd. The smart one. The one who writes the letter to the principal, for chrissake!

When you’re a teenager watching these films, isn’t this what you want? The girl to end up with the guy? By the end, you’re putting yourself in the female protagonist’s shoes, wanting desperately to make out with Chad Michael Murray a la A Cinderella Story. But I can’t help but think back on how I felt after I watched these movies — I wanted makeup, I wanted new clothes, I wanted pretty friends to make me feel pretty. I wanted something I wasn’t. Juxtapose this with a memory I have after watching a Disney Channel classic, Gotta Kick It Up!, one of America Ferrera’s first roles in 2002. This movie was so girl power, it was insane. Although the main character, Daisy, had a man, it didn’t take away from the narrative because viewers are so enthralled with the girls’ stories — how they stuck together and triumphed to compete as a middle school dance team. When the credits started rolling, I immediately went to my soundsystem and turned on some Hilary Duff or something along those lines and just danced. That’s where my mind went; to pure joy.

As we become more aware about what representation means to marginalized folks, it’s important that artists, filmmakers, and other creative people continue to make art for folks who need, and want so desperately, to be seen. We don’t need men to lift us up, to make us feel beautiful, or give us a sense of belonging. That’s why films like Booksmart that center on female friendships and not boys are so revolutionary: because there isn’t really anything that compares to it.

In a 2008 study, “Mean Girls? The Influence Of Gender Portrayals In Teen Movies On Emerging Adults’ Gender-Based Attitudes And Beliefs,” by Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz and Dana E. Mastro, the authors wrote: “Although many teen films claim to empower young women, it is also clear that they rely on gender-stereotyped portrayals, such as the mean girl. This study helps shed light on the influence of exposure to such portrayals on emerging adults’ gender-based beliefs.”

So, rewind to me playing Gretchen Weiners when I was in fifth grade with my friends. Did I have to be mean to play this role? Yes. I was a mean girl, after all. Did viewing this film, and others like it, contribute to the time I printed out a photo of a fellow Battle of the Books member (who, for some context, was deemed “nerdy” and “weird” for being a well-rounded student) and putting it on my dartboard while I threw darts, aiming for her face as a target? (Not kidding.) It’s a long shot, but maybe. Just maybe, these movies, which are written and produced as harmless, mindless enjoyment, seeped into my developing brain and subconsciously made me believe these stereotypes. I had to be mean or judge “uncool” people to be rewarded with a boyfriend, with good looks, with popularity. And I wasn’t even a teenager yet. Let that sink in.

I’m not saying let’s boycott these movies. But let’s note that these were roles that may or may not have shaped our identity as we grew up. And if we compare that with the Bechdel-test approved movies we’re seeing now like Avengers: Endgame, Booksmart, and Eighth Grade, we’ve definitely moved a step in the right direction.

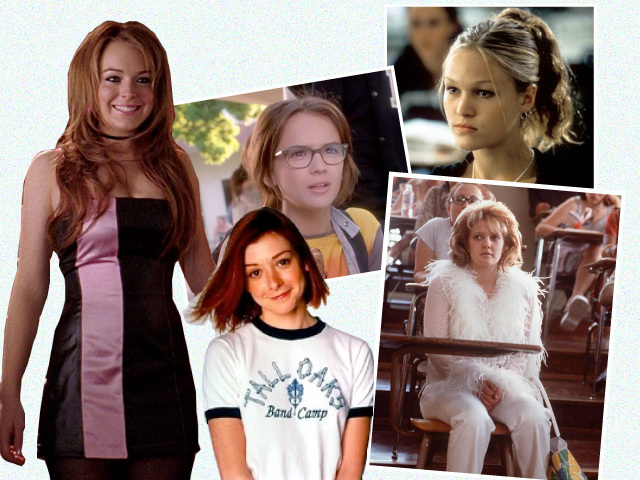

Collage by Olivia Shumate; Photo of Michelle Flaherty in American Pie courtesy of Universal Studios; Photo of Josie Geller in Never Been Kissed courtesy of 20th Century Fox; Photo of Kat Stratford in 10 Things About You courtesy of Getty Images; Photo of Cady Heron in Mean Girls courtesy of Paramount Pictures; Photo of Laney Boggs in She’s All That courtesy of Miramax

More from BUST

What “Josie And The Pussycats” Taught Me About Capitalism, Government Mistrust, And Halter Tops

“You’re Standing On My Neck”: What Daria’s Legacy Means For Weird Girls Everywhere