It is fascinating to see the effect that a popular work of historical fiction can have on revising the public’s beliefs about a traditionally reviled figure like Thomas Cromwell. Of course, one would like to believe that the average everyday reader of historical novels knows the difference between fact and fiction – and the reality is that most of us do. Nevertheless, popular novels, such as Wolf Hall and The Da Vinci Code, do have a profound impact on how once settled history is perceived by both the general public and even by some historians and scholars.

Since the publication of Hilary Mantel’s novel Wolf Hall in 2009, there has been a profusion of non-fiction books published about the life of Thomas Cromwell. To set the record straight, you might suppose. You would suppose wrong. The majority of these books, many by professors and other scholars, endorse the Mantel view of Cromwell.

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, 2009.

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, 2009.

Published in 2014, Tracy Borman’s biography, Thomas Cromwell: The Untold Story of Henry VIII’s Most Faithful Servant, promises to reveal Cromwell as “a caring husband and father, a fiercely loyal servant and friend, and a revolutionary who helped make medieval England into a modern state.”

Published in 2015, Michael Everett’s biography, The Rise and Fall of Thomas Cromwell: Power and Politics in the Reign of Henry VIII, 1485-1534, promises to depict Cromwell “not as the fervent evangelical, Machiavellian politician, or the revolutionary administrator that earlier historians have perceived” but as “a highly capable and efficient servant of the Crown, rising to power not by masterminding Henry VIII’s split with Rome but rather by dint of exceptional skills as an administrator.”

There are more post-Wolf Hall Cromwell biographies, all in the same vein. One purports to be “The True Story of Wolf Hall.” Another is endorsed by Hilary Mantel herself. At face value, it seems that these writers are simply capitalizing on the popularity of Mantel’s novel, much in the way that many did after the phenomenal success of The Da Vinci Code when countless nonfiction books (and documentaries, too) appeared in support of Dan Brown’s fictional narrative about the Holy Grail and Mary Magdalene.

Thomas Cromwell, Portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1532-1533.

Thomas Cromwell, Portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1532-1533.

I explored a little further back to determine the tenor of Thomas Cromwell nonfiction pre-Wolf Hall and was not at all surprised to find that the majority of older biographies were more in line with the version of Cromwell most of us grew up learning about – the cruel, calculating, and ambitious man who “amassed a fortune through bribery and theft” and went to his death begging the king for “mercy, mercy, mercy.”

“This raises the question: Is history an organic thing that changes every few generations to render itself more palatable to the modern masses? Something influenced by entertaining narratives, popular opinion, and bestselling novels? Or is history a series of proven facts which cannot be altered or disputed?”

Barring new evidence – newly discovered documents, for example – I tend to lean toward the latter view. However it is important to consider that many of the records of history that we look to as fact are themselves simply matters of opinion such as letters, journals, and even contemporary accounts written by the prevailing parties after a war or a religious fracture. Documents that often suffer from bias and are, in and of themselves, subject to interpretation.

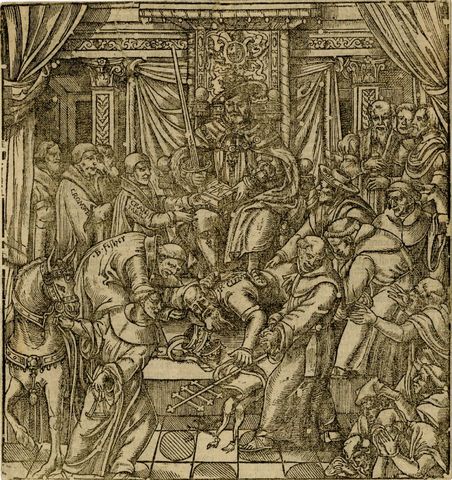

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, woodcut. (Image courtesy of the British Museum) Illustration shows Henry VIII on his throne, with Thomas Cranmer to his left, presenting him with a Bible, while Pope Clement VII is prostrated at his feet. Thomas Cromwell is behind Cranmer.

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, woodcut. (Image courtesy of the British Museum) Illustration shows Henry VIII on his throne, with Thomas Cranmer to his left, presenting him with a Bible, while Pope Clement VII is prostrated at his feet. Thomas Cromwell is behind Cranmer.

So taking into account all of the above, and acknowledging that at present the true character of Thomas Cromwell is very much in dispute, what can I tell you about him? I can tell you that he was born at Putney in 1485. I can tell you that his father was a common man – a brewer, a smith, and apparently a “riotous and quarrelsome” figure.

But wait! Even his parentage is now a subject for debate. Some biographers posit that the man bearing the surname of Cromwell was actually Thomas Cromwell’s stepfather.

In searching through various sources for some common thread, some settled facts which would help to establish an accurate view of the man that was Thomas Cromwell, the only thing that all of the biographers could agree upon was that Cromwell was ambitious. This seems to be a safe enough truth to trust in, for who but an ambitious man could have risen from such poor beginnings to become first a lawyer and then chief minister to the king?

Thomas Cromwell Plaque at the Ancient Scaffold Site on Tower Hill (photo by Bryan MacKinnon, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Thomas Cromwell Plaque at the Ancient Scaffold Site on Tower Hill (photo by Bryan MacKinnon, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Whether Cromwell’s ambition was of the unscrupulous kind is arguable. Many of the pre-Wolf Hall historians seems to think him a Machiavellian figure (see the quotes about Thomas Cromwell in my article Wolf Hall and Sir Thomas More: Historical Fact vs. Historical Fiction HERE.) Most of the post-Wolf Hall scholars are generally of the opinion that his ambition was in no ways unreasonable.

Thomas Cromwell was executed for Treason on the 28th of July 1540. A portion of his final speech to the crowd, made from the scaffold moments before he was beheaded, reads as follows:

“Many have slandered me, and reported that I have been a bearer of such as have maintained evil opinions; which is untrue: but I confess, that like as God, by His Holy Spirit, doth instruct us in the truth, so the devil is ready to seduce us; and I have been seduced.”

Seduced by ambition? Perhaps. Much like everything else about Cromwell at the moment, it’s subject to debate. Just how much of that debate is the result of the popularity of a fictional historical novel, I will leave it for you to decide.

Top photo: Mark Rylance portrays Thomas Cromwell in the BBC adaptation of Wolf Hall. Photograph: BBC

This article originally appeared on MiMiMatthews.com and is reprinted here with permission.

More from BUST

This Publication Included Everything From The Age of Enlightenment, Except Women Of Course

Literature Meets Litigation: How Charles Dickens’s “Bleak” Telling Of Victorian Law Led To Reform

How One Harsh Critic Almost Ended John Keats’ Career And Possibly His Life