Does our current political situation have you wishing you’d paid more attention in civics class? This 101-style breakdown of the U.S. federal government will fill in the blanks so you can understand who’s got what power, and how you can change things

By Elizabeth King

Illustration by Molly Egan

Government is confusing. If we’re going to talk politics, it’s important to note that right off the bat. This stuff is messy and complicated, and it’s easy to get bogged down in all the rules and minutia. But don’t worry; it’s possible (and more important than ever) to get a good grasp on how it all works, especially since the basics haven’t changed since 1787 (for better or worse). And you know what they said on Schoolhouse Rock: knowledge is power!

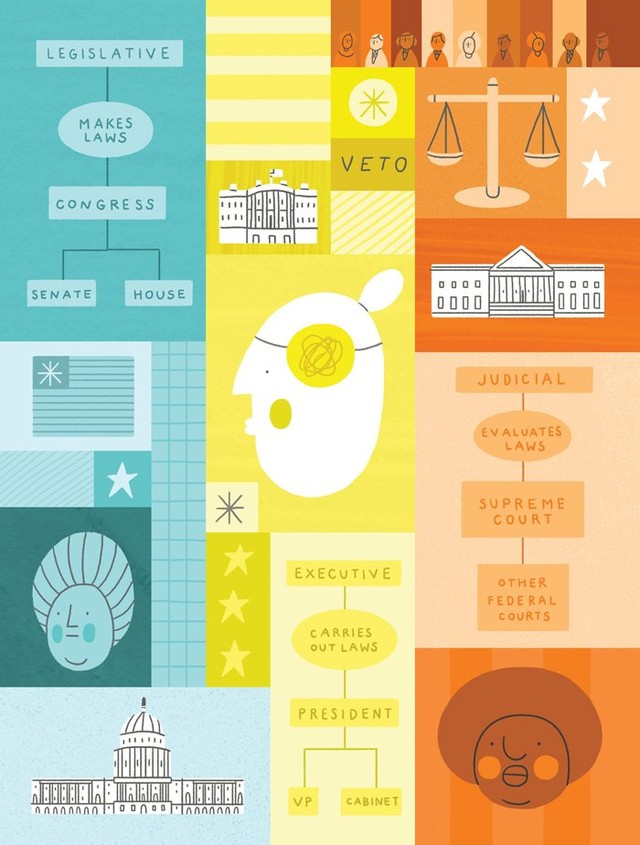

There’s a lot of back and forth about whether the United States’ government is a democracy (a government by and for the people) or a republic (where the “supreme power” lies with the people who have the right to vote for leaders). We can actually consider ourselves a democratic republic. However, it’s important to note that we don’t have a direct democracy, where laws are decided and leaders are elected based on a majority vote by the people. We have a representative democracy, which means we vote for leaders who make policy decisions for us. Some of these leaders nominate other leaders without our vote at all, and they can be found throughout the three branches of government: the executive branch, the legislative branch, and the judicial branch.

Each branch is subject to the Constitution, that ol’ “We the People” missive, which laid out the laws that govern the nation and established the branches, meant to check and balance each other’s influence and power—more on that later. First, let’s dive into each branch: who the heck is running our government and what are they responsible for?

Executive Branch

Many people think of the executive branch as the most powerful part of the government, and in some ways it is. The president heads this branch, all of government, and is also Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

Here’s how the presidency works: every four years, elections are held to choose the next president. But before registered citizens head to the polls, politicians (and apparently doctors, business people, and washed-up reality TV stars) who wish to run for president must file paperwork with the Federal Election Commission. The Constitution requires that presidential candidates be native-born U.S. citizens, have spent at least 14 years living in the U.S., and are 35 years or older. The president is allowed to serve only two terms, for a total of eight years (which feels kind of like forever at this point, doesn’t it?).

It’s not the popular vote that determines the winner of the election, however, which was made blatantly clear this past November. Rather, the president is officially chosen by the Electoral College. So who the hell are these people picking our president? The Electoral College is made up of party representatives in each state (who are nominated and voted on by state party committees). The number of college electors a state has is determined by its population. States with more people (e.g. California, Texas) have more electors than smaller states (e.g. Delaware, Hawaii). The candidate who wins the majority of the votes in the state theoretically wins all of the Electoral College votes (with the exception of Maine and Nebraska, where they can be split). I say theoretically because the Electoral College does not cast their votes until more than a month after Election Day, and electors aren’t required to vote for the nominee who won their state. But electors going rogue is very rare, and unlikely to overturn the expected results. To secure the presidency, a candidate must win at least 270 out of a total of 538 electoral votes.

While the executive branch is not tasked with voting on legislation (except for the vice president, who can break ties in Senate votes, à la Mike Pence’s deciding vote in the appointment of controversial Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos), the president does have the power to create policy by way of signing executive orders—hello, travel ban. These are legally binding documents that do not require pre-approval from Congress (we’ll get to Congress next) and can basically order just about anything the president wants. Though federal courts can temporarily freeze orders, the only way to permanently kill one is to have it revoked by a subsequent president or declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court (more on that system later, too).

The executive branch also includes the vice president, who is chosen by a presidential candidate during their campaign, to be their right-hand advisor and leader of the Senate. The VP also takes over the presidency should the president die, get impeached, or otherwise be unable to serve.

The president’s cabinet—essentially an advisory committee of 15 positions that lead various departments—is also part of the executive branch. Cabinet members are nominated by the president, and must be confirmed by the Senate, which is literally the only requirement for being sworn into the position. All cabinet members advise the president on matters related to the responsibilities of their respective departments, which vary in size depending on the departments’ budgets, from several thousand employees (Department of Education) to several million employees (Department of—what else?—Defense).

A number of non-cabinet agencies reside in the executive branch, too, like the Environmental Protection Agency, which enforces environmental regulations. And the president has other advisors beyond the cabinet as well. For example, Trump appointed Steve Bannon (formerly of right-wing propaganda site Breitbart) as his chief strategist, a position solely at the president’s discretion. The same is true for the president’s Chief of Staff—currently Reince Priebus—and other senior advisers the president leans on for support (like Jared Kushner, who’s married to Trump’s daughter, Ivanka).

Whew! Clearly this branch has a lot going on, but there’s (usually) not much legislative action on this level of government. That’s where this next branch comes in.

Executive Cabinet

—————————————-

Secretary of State: Handles foreign affairs on behalf of the U.S.

Secretary of the Treasury: Advises about financial, economic, and tax policies.

Secretary of Defense: Second only to the president when it comes to direct power of the military.

Attorney General: Provides legal counsel to the prez, government agencies, and legislatures, and heads the Department of Justice.

Secretary of the Interior: Leads the department responsible for managing the country’s land, wildlife, and natural resources.

Secretary of Agriculture: Runs the USDA and oversees the nation’s farming industry.

Secretary of Commerce: Advises on foreign and domestic commerce as well as U.S. job creation.

Secretary of Labor: Heads the department that enforces laws related to workers, unions, job seekers, and retirees.

Secretary of Health and Human Services: Heads the department concerned with health matters such as insurance and Medicaid, as well as welfare and income security.

Secretary of Housing and Urban Development: Oversees the nation’s housing needs, including community development and affordable housing.

Secretary of Transportation: Deals with policy related to transportation.

Secretary of Energy: Heads the department that deals mostly with environmental policies.

Secretary of Education: Advises on education policy matters and heads the department responsible for improving the public school system.

Secretary of Veterans Affairs: Oversees the department that provides a variety of services, including healthcare, to veterans.

Secretary of Homeland Security: Advises on matters related to protecting the U.S. from foreign and domestic terrorism; this department’s also responsible for responding to natural disasters.

—————————————-

Legislative Branch

While the executive branch is made up of many positions filled by one person each, the legislative branch consists of two main positions filled by many different people. The two bodies of Congress, the Senate and the House of Representatives, comprise the legislative arm of government and are charged with deciding what becomes law and what doesn’t.

So who fills the Senate and the House? The Senate is made up of two senators per state, for a total of 100. The House is much bigger than the Senate, as representatives are determined by each state’s population size. For example, California, the nation’s most populous state, has 53 representatives in the House (yowza), whereas 7 less-populated states (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming) each have only one representative. These folks are lead by the Speaker of the House (currently Paul Ryan), who is elected by House members. The idea is that Senators and Representatives look out for the best interests of their constituents at home. (Though the truth is, of course, much more complicated. Google “congressional lobbying” and brace yourself.)

And how do these folks get their jobs in the Capitol? Both senators and representatives are elected by residents of the state they represent, but in different ways, and often at different times. Senate races occur every six years and voters registered anywhere in the state can vote in them. Candidates for the House of Representatives run in their district, which can be thought of as a zone within a state, and are voted on by residents in their district every two years. Both senators and representatives can serve unlimited six- and two-year terms, respectively.

Now on to what Congress gets up to. Congress is responsible for passing federal laws, all of which start out as bills—drafts of would-be laws sponsored by members of Congress—and are then presented to the House. There, the bill is taken to a Committee of experts in the House who pore over and research it; in some cases, the bill goes to subcommittee for extra expertise. Once the Committee is satisfied, the bill is reported to the House, debated, and changed some more before the House takes the bill to a vote.

If the bill passes the House, it goes to the Senate, where it undergoes much the same treatment: it goes to a Senate committee, is debated on the Senate floor, and is then voted on by senators. Next stop for the bill? The White House! The president can either sign the bill, making it a law (finally!), or veto it. In the event of a presidential veto, the bill can be voted on once again by members of Congress. If two-thirds of the House and Senate vote in favor of the bill, the veto is overridden and the bill becomes a law, a clear check on the president’s power. Likewise, the president has a check on Congress, and can veto bills that don’t fit his/her agenda. To give you a sense of how few bills successfully make it through this process, according to govtrack.us, the 114th session of Congress (January 6, 2015 — January 3, 2017) introduced 12,063 items of legislation. The total number of enacted laws? Just 329.

But what if a law doesn’t seem right, or citizens are concerned that a law will be harmful once implemented? This is where the courts, located in the judicial branch of government, come into play.

Judicial Branch

The highest court in the nation is the Supreme Court (often referred to as SCOTUS). Supreme Court Justices, like cabinet members, are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. However: Supreme Court Justices serve in their position for life (long live Ruth Bader Ginsburg!) or until they choose to retire (they can also be impeached and removed by Congress). Getting a Justice into the Supreme Court is one major way presidents can have a long-lasting impact on policy. Congress has the power and discretion to determine the size of the Court; it has been as few as six, though it’s been nine since 1869 (in actuality, we’ve had only eight justices since Antonin Scalia died suddenly in early 2016, but President Trump has nominated Neil Gorsuch to fill the seat).

The Supreme Court gets around 7,000 requests to hear cases each year, but only hears about 80 of them, and decides an additional 50 cases or so without hearing them, according to supremecourt.gov. The Supreme Court primarily hears cases that involve interpretation of the Constitution, and thus have an impact on the whole country, and not just the individuals who bring the case before the Court. This means that legislation passed by Congress (or at the state level, as was the case that resulted in the legalization of same-sex marriage), that is constitutionally questionable, can potentially be heard by the Supreme Court, which can effectively do away with the law.

The Supreme Court uses “the rule of four” to determine whether it will hear a case: if four justices think it should be heard, the parties are allowed to present their case. The Court issues a writ of certiori, a legal order that requires the lower courts that previously heard the case to send over their records. Then, each side writes up a brief before oral arguments are heard. Justices often ask attorneys questions throughout the arguments. When the arguments are over, the Justices convene to discuss the case and the majority opinion ultimately determines the decision. One Justice on the majority side writes up the majority opinion, a document that lays out all the reasons for the decision. The minority side writes up their own opinion, called a dissent, explaining why they disagree with the majority.

The primary checks on the Supreme Court come during the Justice nomination process, but after that, the Supreme Court’s decisions are literally the law of the land. Congress and state-level legislature can pass laws that lessen the impact of Court rulings (like how states pass laws that make it all but impossible for abortion clinics to stay open), but only the Supreme Court can overturn its own ruling.

While all of this may seem to work out nice and neat on paper, it’s important to understand that government is messy, and checks and balances don’t always work the way we might hope. For example, imagine a very conservative bill presented to a House comprised of a majority of Republicans. A nice check would be a majority of Democrats in the Senate to alter the bill’s contents or shut it down completely. However, if the Senate is also majority Republican, the bill is likely to sail through, and if the president is a Republican, the bill is likely to become a law without any meaningful opposition. The law could always then be taken before the Supreme Court, but if the Court is made up of conservatives, there’s no remaining recourse until the composition of federal government changes and the law could potentially be repealed. Remember earlier where we talked about Senate and House elections? They’re crucial. A number of seats are open in Congress and will be voted on during the 2018 mid-term elections. Check to see when your Senators’ and Representatives’ terms are up and if they’re facing re-election this year. Voting is the most effective way to turn the tide.

Suffice it to say, a lot goes down in Washington that we the people are not privy to and don’t have any direct control over. But that’s why it’s super important to stay apprised of current events and get involved at the local, state, and federal levels of government. The government is supposed to work for us, so let’s make sure it does.

More from BUST

Now States Can Choose To Defund Planned Parenthood, Thanks To Mike Pence’s Tie-Breaking Vote

Samantha Bee Has A Few Words About Trump’s Failure Of A Healthcare Proposal

Iowa Bans Abortions After 20 Weeks. Which State Will Be Next?

social share photo: Edmond Dantès from Pexels: https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-woman-with-a-badge-7103173/