Lauded as the debut novel of the season, The Other’s Gold follows four friends from their first days of college through the first decade of their adulthood – a messy time of burgeoning and becoming. The demands of family, friendship, desire, and rage shape the four friends’ identities even as they push against the bounds of loyalty, shame, institutional power, and the patriarchy. I found so much to think about in this spirited, complicated joy. From her home in Boston and mine in Seattle, Elizabeth Ames and I corresponded by email for this interview.

The Other’s Gold braids together the lives of four women who meet in college, become fast friends, and then experience the tumultuous period of their own coming-of-age through new motherhood. How did you create these characters?

I just tried to write good sentences and scenes, to write into the characters and then see what they would do. By the time I finished, they really were acting of their own volition, and that is not to undermine the time or effort spent writing the book, only to say that for me that’s the great pleasure of this work, to spend enough time in the company of these invented people that, by the end, I get to follow them around, and they surprise even me sometimes.

For the past few years you’ve been living in a Harvard dormitory with your husband, who’s pursuing a PhD, and your two young children. It’s a sort of immersion-journalism life you’re living, only you write fiction! How has your living situation inspired your writing in other ways beyond the obvious setting of the opening chapters?

When we first moved in I was wearing my then six-month-old everywhere, and when the students moved in, many dropped off by their parents, I was sort of crushed by how much love I felt for these two groups—the students and their parents, for their respective and conflicting longings. Earlier that year, I remember seeing an April Fools’ day joke posted in a babywearing Facebook group about the “college carrier,” designed so that parents could wear their 18-year-olds to that first dorm drop-off, and I hardly found it funny, so convinced that I would never be able to take my baby out of her carrier. All this to say that I felt very connected to the encompassing nature of new parenthood, but quite removed from the transformative intensity of those early college days.

I was fascinated by the friendships I observed, but it wasn’t so much envy or nostalgia that propelled me. Writing about a group of college friends became a way to imagine myself back into that time, and to invent the kind of encompassing friend quartet that I didn’t have. I’ve been very lucky to have the enduring and sustaining friendships that I do, but in college I was never part of a friend family like the one in the book, and I found myself so curious about what it would be like.

Lainey, Alice, Margaret and Ji Sun each make “a terrible mistake” over the course of the book. And for each of them, the backstory of the mistake is grounded in some deeper, past shame. How did you think about the counterbalancing forces of shame and power as you developed your characters’ plotlines?

I’m so interested in the way you pair shame and power here, as yes, the wresting of power back from those who harmed the characters, or caused them shame, does propel much of the action. It’s very uncomfortable to consider how Alice, whose life is in some ways organized around trying to overcome the shame she feels at the harm she caused her brother, can also recall how in that same anguished moment, when she made such a terrible choice, she felt not only shame and grief, but also power. The characters angle for agency, but they each also reckon with the costs of too much power: Alice lamenting what she did with her power; Ji Sun failing to employ the full force of her power; and, later, Margaret and Lainey abusing their powers as they become adults, and mothers.

Lainey’s mistake in particular illustrates the terror that comes with too much power, and becoming a mother crystallizes this reckoning with power, too, as we are meant to be our children’s greatest protector, but we immediately become so painfully, acutely aware of our powerlessness, as well as the terror of that responsibility.

I particularly loved these lines of Ji Sun’s, where she finds herself “struck by how easy it was to misinterpret desires: for comfort, for knowledge, for acceptance. All these ways people wanted to connect with each other that weren’t about sex, but that is was easy to mistake as such, especially here, with all their bodies so electrified by the urgency of awakening to their powers.” It seems to me that each of the mistakes the friends make is a misinterpretation of desire, and a reckoning with one’s own power. How do you see it?

That is a very astute reading, thank you. And yes, misunderstanding desire, even one’s owndesires, does propel some of the mistakes in the book, as does, certainly, a reckoning with the force and limitations of one’s powers. We desire things from others that those people cannot possibly give. Our babies can’t rescue us from how harrowing it is to confront the power we have over them, or the absolute lack of control we have over so many aspects of their lives. Our intellectual heroes can’t, in their private lives, satisfy our desires that they model how to live. We want so much from one another! And our longings are so often so impossible to communicate, let alone satisfy.

One review noted that your characters don’t suffer “sufficient retribution” for their “bad decisions.” I think your character Margaret says it most bluntly when she says to the others: “I hope you learn something about how not everything is so black and white!” But I also think there are varying types and degrees of retribution—both internal and external—for every mistake we make. And much as perhaps we’d like it to be, retribution is often notcorrelated with the severity of the crime. What’s your take?

Retribution is almost never correlated with the severity of a crime. Only those with the power to mete out retribution seem interested in whether or not it’s “sufficient.” (I will admit genuine curiosity as to what constitutes “sufficient retribution,” as well as how one grows confident enough to believe that they know.)

As you point out, the characters do suffer in ways for their mistakes, though the closest anyone comes to eye-for-an-eye vengeance is perhaps Lainey when she attempts to punish herself with the same type of violence she cannot believe she inflicted. The characters all cause and experience harm, and the book investigates the consequences of facing trauma and refusing to, and suggests that both have their costs. We punish ourselves and one another for the pain we cause. What is the metric for retribution? Who decides?

The occupation of space was a driving theme of this book that I kept coming back to, occupation being a way of spending time, the act of living or being in a place, and an assertion of power. So much of our current political debate revolves around the space that women and women’s voices take up, or the space women are given, or the space women are claiming or re-claiming for themselves. I don’t know that I’ve seen a novel deal in such a demanding way with these ideas—logistically, politically, and emotionally.

I appreciate the way you link the logistical, political, and emotional forces at work in the book, and your singling out of the notion of occupation, and even how much work that word does, is compelling. As to when and how we take up space, the characters are receiving a constant education in that regard, from their families, their teachers, their romantic partners, and each other. I would say I’m receiving my own ongoing education in this regard, too, and that these questions come up in the book because I don’t know how to answer them, but am obsessed with thinking about them.

The four friends reveal so many things about themselves to each other, but some secrets remain, both past and present. I’m thinking particularly about Ji Sun and Adam’s relationship. Of all the transgressions, this is the only one that’s committed internally, one of the four friends potentially hurting another of the four. We don’t see far out enough in the future to know if this secret is ever revealed or discovered, but I wondered if this could potentially break the foursome. It’s another way of getting at the question of forgiveness, a current that runs through the book. How much, and under what circumstances, can we, should we forgive?

And how can we keep forgiving? Forgiveness is ongoing, evolving, and in some ways quite tedious. We would all love the relief of forgiving or of being forgiven in one fell swoop. But we know that even when forgiveness is offered, the shame of hurting someone can endure, as can the pain of being hurt, even if we are desperate to be free from it.

In “Bad TV,” an essay from the spring 2018 issue of n+1, Andrea Long Chu writes: “Whether or not men deserve forgiveness—and if so, which ones—is not the question, much less the answer. In fact, there is no question. The reality is harder. What hurts isn’t when the people we love do unlovable things. What hurts is when, afterward, we still love them.”

These characters are all living in the afterward, still loving one another, still hoping their friends will find them worthy of love. Lainey would most certainly still love Adam and Ji Sun in the wake of learning what they’d done. But as to whether she would forgive them, I’m not sure. I think one hazard of being so close to all of these characters is that I understand and identify with their motivations, if not their actions, and so I’ve found myself agreeing at times with Ji Sun that Lainey might actual appreciatethat Adam and Ji Sun relieved some of the tension that defined their relationship! And at other times I think, are you kidding me, Lainey would, upon learning, light the place on fire! The support that Ji Sun offers Lainey, especially in the immediate aftermath of Lainey’s mistake, is so vital, though, that I think Adam and Ji Sun would protect that at all costs, and not dare reveal what happened between them, at least not for a long time. I wonder if what transpired might grow to feel more and more like a daydream or a fantasy to both Ji Sun and Adam, if they will be able to convince themselves that they imagined it, or that it happened on a different plane, in one of those previously hidden realms, accessible only when grief tears open a temporary entryway.

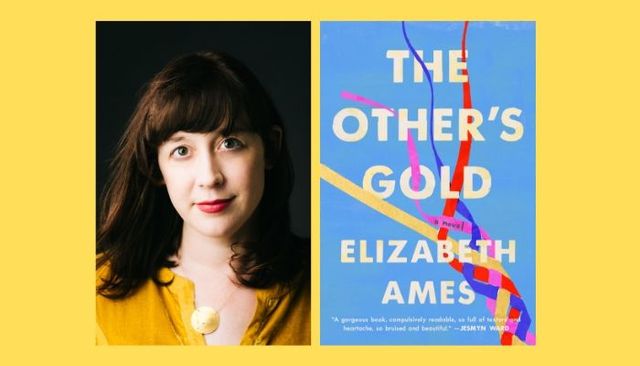

Another line I loved came toward the end of the book, again from Ji Sun’s point of view: “It was not possible to rescue anyone, she knew by now, but you could recognize her. You could see what she showed you, flinch and keep looking, let her find in your own face the truth.” To me, this is the ultimate definition of friendship. But it can be hard—to “flinch and keep looking.” We all have friendships that have come undone over time or circumstance. When I look at your beautiful book cover, there are two interpretations—one is that of a lanyard being braided together, and the other is of it unravelling. Have you imagined a future for your characters? Can you envision a sequel following them into middle age?

I’m so grateful that that line spoke to you; it encapsulates much of what is important to me about the book, and about friendship. And yes, that’s an aspect of Jaya Miceli’s beautiful cover art that I so appreciate, that the braid is both unraveling and coming together. I love the way those threads feel like banners, too, or rivulets, with a movement that seems both joyful and mournful. Jaya is amazing.

Much about the ending was discovered along the way, but from very early in the writing process I had the sense that near the end of the book there would be a toddler careening near waves, just getting landlegs. I wanted to leave them when they still had very small children. I wanted also to never leave them, but I couldn’t bear in some ways to follow them into 2016-17, years in which I cloistered myself in the world of this book against the horror of who became our president. I think of them on that beach, not yet knowing, and it’s a bit breathtaking how badly I want to protect them from what’s coming down the from the darkness next.

But I am so grateful when people ask about a sequel because it speaks to what I love best in books, art, life itself: just wanting more time with these people.

This interview has been condensed.

Author portrait by Adrianne Mathiowetz

More from BUST

Candice Carty-Williams’s “Queenie” Is The Ultimate Millennial Downward Spiral

Nell Zink’s “Doxology” Blends Punk And Politics To A Post 9/11 U.S.

Elizabeth McCracken’s Newest Book Is A Triumphant Return