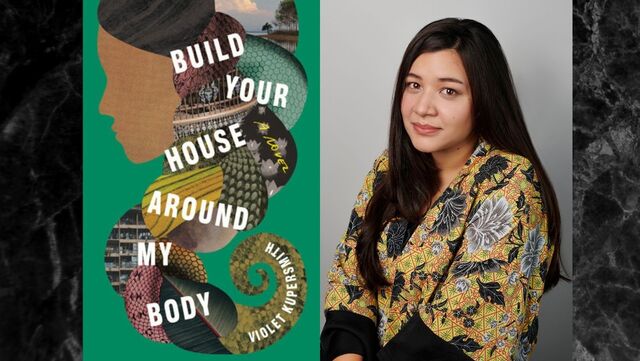

A story of possession and consumption, of loneliness and rootlessness, of anger and revenge. In her debut novel, Build Your House Around My Body, Violet Kupersmith manages to do so much and to do it all so well.

Winnie is a young American woman, aimless and living abroad, when she suddenly disappears without a trace in Vietnam. As the reader uncovers what’s happened to Winnie, they’re taken on a whirlwind, hair-raising adventure through time and place. A large cast of characters that includes angry women, vengeful spirits, ghost hunters, and ambitious Frenchmen, are all woven together to form a sweeping story that covers decades of Vietnamese history and confronts topics from misogyny and colonialism to family and trauma. The novel jumps from one time period to another and back again, as the reader discovers the mysteries surrounding each of the characters and how they all connect, creating an engrossing novel that’s furious, shocking, and poignant.

Here, Violet discusses books, writing, and ghost stories.

Both your first book, The Frangipani Hotel, and your new novel, Build Your House Around My Body, use elements of horror and the supernatural. Is there something about those genres that you feel is particularly apt at conveying the stories you’re trying to tell?

Absolutely. Just for me personally, it felt like a way into the material, into the subject of Vietnamese Americans, and war trauma, and just my way of writing something that hasn’t really been written before, in a way that only I really felt like I could do it. Because I grew up with those stories, and it felt like uncharted territory in a genre that felt kind of saturated with stories where people drew on their own experiences and I didn’t have the experience of being a refugee, in my first collection when I started writing about the Vietnamese diaspora. So that’s what drew me to it originally and there’s just the delicious opportunity with speculative fiction to kind of – you have all this extra margin room to just play with things and do different things when the physics of the regular world can get bent a little bit.

The book follows multiple timelines, and also has quite a few characters, but everything fits together so seamlessly, what was planning all of that like? Or was there planning?

Well planning was a mess [laughs]. Originally I pictured it as a kind of tryptic, with three novellas following these similar characters. And then when I started interweaving them, that’s when the story felt more like a novel instead of three poorly connected novellas. I describe the process as kind of trying to do a crossword puzzle, like trying to construct one. Little connections would kind of write themselves, which was fun. It does ask a lot of the reader, there’s a lot to keep track of. I hope the readers know, my baby birds, they’re all going to connect. You don’t have to do the work because I did it for you. All of the wires are going to connect at some point.

It is nonlinear, what made you decide to write it that way? Did you ever decide to do it a different way?

Yeah, I originally tried having it in a number of different organizational structures, but this architecture, it felt like it captured the kind of disorienting experience that I wanted to create for the reader. I wanted to have them time hop, to sort of show that all of these times are existing parallel to each other because that’s kind of how memory works, and how trauma works, and the history of this country, it doesn’t really go away. And so it just felt fitting to me, in a way, that the chronology didn’t work. And I think that it would’ve been really weird to start where the farthest point in time was, which was the French rubber plantation. I mean, it could’ve worked maybe in the hands of another writer but this felt like the form that this story wanted and needed, the jumping around.

So the book takes place in Vietnam, but in several different places within the country. And you yourself, I think, lived and wrote in some of those places. How did place influence the novel?

The setting really is where I start with the chapter or the idea. So I moved to Da Lat in 2013, because it was historically very haunted and because it has this legacy as this French playground that they built for themselves. What a weird place, an incredibly spooky place just physically because it’s full of freaky mist and also these falling apart houses and these terrifying forests, and I thought, ‘well, if I’m going to write a ghost novel, I might as well start here.’ And it was kind of the gateway to the Central Highlands, which I started traveling to because of this bad ex-boyfriend [laughs], so I would go on these long motorbike rides back to his little tiny home hill town and I felt this kind of affinity for these weird hill country areas, like around Pleiku and Dak Lak because they’re just these remote, barren expanses — but so beautiful, and it reminded me in a weird way of where I’m originally from in Central Pennsylvania. [What] I was imagining when I wrote about Binh, and Tan, and Long and their childhood, it’s kind of like a Vietnamese parallel for maybe what my life would have looked like if I had stayed in coal country, when I was like, six.

So, you lived in a haunted city. Do you have any good ghost stories or experiences?

Well I made the mistake of trying to spend the night in one of the haunted French villas in the forest with a journalist friend. I was like, ‘I’m [going to] go seek an experience’ and it ended with me making everyone leave at 3:30 in the morning because I heard creepy footsteps that were not from a body. I heard gravel footsteps and then I made us leave. I was the only girl there and so it became kind of the trope of the hysterical woman, which was very annoying. They were like, ‘Oh, if we stay we can have an experience.’ I was like, ‘an experience of getting eaten by the ghost?’ And that kind of fed into the novel too — the sounds in the madhouse.

Was there a section that was harder to write than the others?

The Winnie timeline. The Winnie storyline was tricky because I think she is a very guarded character and she was hard to coax out. I originally didn’t even want her to have a huge storyline because I was interested in doing something where the Vietnamese characters are central and the Vietnamese-Americans are on the periphery. But then it became sort of clear when I was into year four of writing this novel and it wasn’t coming together I was like, ‘Okay, Winnie, we’re going to give you a bigger role, we’re going to try and see how this goes’. It’s funny to me, looking back on it, because her vacancy is so central to who she is as a person and the story itself is framed around her literal disappearance, and her literal vacancy. It seemed fitting, but it was tricky to coax out even though she and I sort of shared the most DNA and the most experiences of being a 22-year-old, biracial, Vietnamese American teacher. So it was harder to write that than being a ghost hunter in the 80s, which I have never been.

I loved Winnie, and really all of the women in the book. But I was really struck by the way they were treated and also the way they reacted to that treatment. Could you talk about what you were thinking when you wrote them?

I wanted women’s anger to be at the center of the story, and for the novel to shine a light on the everyday misogyny that happens to women in Vietnam, [to] women everywhere. And it was important to me that there’s not – I hate perfect victim narratives. [The characters are] real to me, and I wanted them to seem real to other people. And the different ways in which they process their trauma and which it transforms them and how they choose – what they choose to become at the end, I wanted there to be different paths for them. There’s not a lesson in the story about what you should do with your own pain, because I didn’t know what to do with mine. I guess I put mine into a book. It doesn’t do justice exactly, but it does revenge in a small way.

One of the things I loved about the novel is how the reader had access to so many different perspectives. Was that always the plan? What made you decide to tell it that way?

I think it’s informed by my own sort of fractured identity, and I’m not comfortable writing only in one perspective so I thought if this book is coming from this sort of hybrid writer, this hybrid take on Vietnam, it’s going to mimic that in the actual, literal structure and perspective. I wanted it to be like a chorus of voices, to be polyphonic. I wanted it to mimic what it is to be in Vietnam — it’s crackling, it’s alive. It’s so noisy and it’s wonderful. And I wanted to try to do that for the reader too. Assault on the senses, things coming at you from every different direction, let it wash over you.

Speaking of assault on the senses, in the novel, your descriptions of food, they walk this line between making me want to eat what you’re describing and being kind of gross. What went into that?

Yeah, well I think – I wrote a lot of it when I was hungry too [laughs]. I was living in England and I had just moved from Vietnam and I was just really hungry and trying to recreate it. I loved how you described that kind of fine line, because that’s what I wanted from all the description of consumption, and egesting, and just the way the book treats the body as like a really gross, but extraordinary thing in different ways. I mean that’s what a lot of my experiences in Vietnam too, I noticed, were sort of central expat experiences. Food was a way of eating the culture. Their rubric for what kind of foreigner they were and what kind of foreigner they wanted to be, and to present to the world. And I just love food metaphors. I love food.

Is there a character you most relate to or identify with?

I think of the mixed-race characters, I feel sort of closest to the Fortune Teller. But also just the idea of a fortune teller as a vessel for a different power. In my case, a creative channel for the story. That’s how it felt when I was writing it, like I was a kind of spirit medium. Also, I just feel like a dog [laughs]. I’m Belly at the end, like running around gleeful in a body, trying to eat what I can. I think I’m a cross between Belly and the Fortune Teller.

Who would you say your writing influences are?

I think a big influence is David Mitchell, just in terms of someone I look up to for breadth of imagination and extraordinary story construction. He can hold together something that seems so big and so delicate. Also, I’m very inspired by the weirdness of Haruki Murakami. Angela Carter and Shirley Jackson – how those two in particular write about women. I love Kazuo Ishiguro and his early works about identity, and Asian-European identity and challenges. And watching [his] career trajectory, it’s really inspiring to see how he moved on from Pale View of the Hills and When We Were Orphans. I think my favorite writer ever is Elif Batuman, the Turkish-American writer who wrote The Idiot, which I think is just the most perfect exploration of a rootless Winnie young person in a foreign country. And it’s just so funny, she’s the funniest, best writer and I will push The Idiot on anyone who hasn’t read it yet.

Okay, last question: what’s next?

I think I want to do another novel. When I was in the throes of wrestling with Build Your House [Around My Body], I was like, ‘I’m never going to do this again. Why did I think this was a good idea? I miss short stories, they’re so nice and small and easily digestible.’ But now that I’m on the other side of it, I just miss having that much space to work with, it’s kind of intoxicating. And so I’m excited to write another novel next. And I’m not sure how ghosty and how Vietnamese it’s going to be. It’s interesting, because I feel like a lot of that just went into Build Your House and I don’t know if I’ll feel the need to stay in the same subject area. I feel like it’s always going to be weird, what I write. I think I’m always going to write something in that kind of margin-y area, where I have more room to play and explore these kind of sneakier, slipperier subjects of identity, and memory, and loss, and my family’s own story of displacement and dislocation, but I don’t know what form that’s going to take. I’m having fun just enjoying my Build Your House child being out in the world and thinking of future siblings for it.

Build Your House Around My Body is out now!

Buy it here or at your local bookstore.

Top photo credits: Book cover via Penguin Random House, Headshot via Adriana De Cervantes

More from BUST

TV Writer Danielle Henderson Gets Personal With Her Memoir, “The Ugly Cry”: BUST Interview