In January 1818, on the second page of a small Irish newspaper, was a brief article with the sensational headline: “Projected Divorce in High Life.” This case, which would soon become notorious in both England and France, was not, in fact, a divorce. It was an action for criminal conversation—a tort, long extinct, in which an aggrieved husband could make a claim for damages against the lover of his adulterous spouse. These sorts of cases were always deliciously scandalous, and none more so than that of Aston v. Elliot—a case which involved noblemen, sex workers, syphilis, a veteran of Waterloo, and some of the highest ranking members of the beau monde.

A Brief History of the Parties

The article in the January 22nd issue of Saunders Newsletter was printed well before all of the facts were known to the public. As such, it is very much on the side of the husband, Colonel Harvey Aston (known in some publications simply as Harvey Aston, Esq.) of Aston Hall, Warrington, Lancashire. Attributing its information to “chit-chat in certain fashionable circles,” the article begins by describing Aston as a relation of a “certain Marquis in high court favour” and goes on to praise his courage in the Peninsula, where he served under his particular friend, “the gallant Wellington.” It was in the Peninsula that, according to Saunders: “While thus ardently engaged in the pursuit of conquest…he himself was conquered by the bewitching glances of his present wife—a Spaniard by birth, and possessing all those nameless attractions for which the females of that country are so much celebrated.”

Saunders goes on to explain how, despite the warnings issued by his “more prudent companions,” Aston “surrendered his whole heart to the enchanting foreigner.” Predictably, this alliance was not a happy one. Saunders reports that Aston’s desire soon cooled and “his ordinary perceptions resumed their empire,” writing, “Then it was he saw his error; and subsequent circumstances, it is stated, convinced him that having entrusted his honour to the keeping of another, it was no longer safe.”

The bewitching Spanish foreigner was actually the daughter of an Irish gentleman named Mr. Barron who had settled in Cadiz as a merchant. Her name was Margarita and she is described in later publications as being “lovely in her person and fascinating in her manners.” She met Aston in Cadiz in 1813. They were married shortly thereafter and, upon returning to England in 1814, they repeated the marriage ceremony at St. James’s. They soon welcomed their first child.

In 1816, they removed to France where they set up house at Passy, two miles outside of Paris. There, they welcomed a second child—a birth celebrated with a splendid entertainment hosted by the child’s godparent, the Duke of Wellington.

It was while living in Passy that Margarita Aston met Edward Elliot.

The Right Honourable Hugh Elliot, Governor of Madras, 1752-1830. (Father of Edward Elliot.)

The Right Honourable Hugh Elliot, Governor of Madras, 1752-1830. (Father of Edward Elliot.)

Captain Edward Francis Elliot (sometimes spelled Elliott) was the twenty-year-old son of the Governor of Madras. He was related to both the Earl of Minto and the Earl of Auckland, and had been present at the Battle of Waterloo. Initially, he and Aston had been friends, but in time, his attentions turned solely to Aston’s wife. Whenever her husband was absent, Elliot would come to visit her. When their clandestine meetings were discovered, Aston barred Elliot from the premises, after which Elliot continued his visits in secret, entering the house through a backdoor.

Criminal Conversation

Eventually, letters between the two alleged lovers were intercepted and this, combined with the observations of French servants who claimed to have seen the couple together on several occasions, was enough to compel Aston to bring an action for criminal conversation against Captain Elliot, seeking £10,000 in damages.

Trial of Rev. Edward Irving, 1823.

Trial of Rev. Edward Irving, 1823.

The case made news in most of the magazines and daily papers of the day, with pre-trial articles roughly resembling some version of the following, which was printed in the February 28, 1818 issue of the Huntingdon, Bedford and Peterborough Gazette:

Crim. Con. — An Action, which will shortly be tried in the Court of King’s Bench, is brought by Colonel Harvey Aston, whose father was so well known in the fashionable world, against Captain Elliott, a nephew of Lord Minto. The Defendant, who is a Captain in the Engineers, was present at the battle of Waterloo. The Lady’s name was Barron, being the daughter of a Mr. Barron, an Irish Gentleman, who had settled at Cadiz as a merchant, at which place she was born. The adultery is alleged to have taken place at Passey, near Paris, to prove which several servants will be called. Letters were intercepted from the defendant to the plaintiff’s wife. Lord William Gorden, Captain Seymour, of the Guards, besides others, will be called to prove the happy manner in which the plaintiff and his wife lived, before the alleged adultery took place. The defendant was on intimate terms with the plaintiff, and often dined at his table. Several counsel are engaged on the part of the plaintiff; Mr. Gurney will take the lead. The damages are laid at 10,000l. The jewels, which Mrs. Aston had obtained, amounting to upwards of 4000l., are now in the plaintiff’s possession.

The trial took place on Saturday December 12, 1818, with the next day’s edition of The Examiner reporting that “the Court was crowded to excess during the whole of the trial, as the parties it seems moved in the highest circles, both English and French at Paris. The trial lasted from three till past eight at night.”

Court of King’s Bench, Westminster Hall, 1808. (Microcosm of London)

Court of King’s Bench, Westminster Hall, 1808. (Microcosm of London)

The Case for the Plaintiff

During an action for criminal conversation, the husband, wife, and defendant do not take the stand. Instead, various witnesses are called forth. In the trial of Aston v. Elliot, Mr. Gurney began by calling Captain Henry Menel of the Royal Navy who testified that, before Elliot appeared on the scene, Mr. and Mrs. Aston were “on the most harmonious of terms.”

A French servant, by the name of Antonio Sarrazy, was then called to the stand. He testified that Elliot visited Mrs. Aston without the knowledge of her husband, that he used the back door of the saloon to gain entrance to the house, and that he came almost every day. Sarrazy, who admitted to still being in the employ of Mr. Aston, went on to claim that he had taken many letters from Mrs. Aston to Elliot and that, during her daily trips into Paris, Elliot would meet Mrs. Aston and ride in the carriage with her. According to the December 26th edition of the Westmoreland Gazette:

Witness remembers one evening being caught in a shower of rain, and turning round to get an umbrella he observed Mrs. Aston sitting on Mr. Elliott’s knee. Witness then went on to describe what more he saw, which left no doubt what then passed; it was then about twelve at night; the witness was enabled to see what was passing at this time in the carriage, by the reflection of a lamp by the side of the road.

The Vicar of Wakefield, Attendance on a Nobleman by Thomas Rowlandson, 1817.

The Vicar of Wakefield, Attendance on a Nobleman by Thomas Rowlandson, 1817.

Mr. Gurney then called Mrs. Aston’s French wet-nurse, Julia Retour. Retour testified that Mrs. Aston was accustomed to receiving Elliot in her saloon. Retour stated that, on one occasion, she had entered the saloon to find Mrs. Aston and Elliot kissing and, on another, she entered to find them in “a very improper situation.” Even more scandalous, the Westmoreland Gazette reports Retour’s recollection of one particular incident:

Witness remembered going into Mrs. Aston’s one evening for something for the child, when she observed Mr. Elliott in Mrs. Aston’s bed. — Mr. Aston was at that time in Paris, and did not return home till two o’clock. Mr. Elliott called witness to him and offered her money, but witness refused it, and hastened out of the room.

More evidence for the plaintiff followed, including the testimony of his valet and one Mr. Marryat, from Cox and Greenwood’s, who testified that Edward Elliot was presently on half-pay and had no other income on which to support himself.

Mr. Gurney then closed his case by reading aloud from several of the love letters that Elliot had written to Mrs. Aston. A December 20, 1818 issue of Bell’s Weekly Messenger provided transcripts of two of these letters, one of which Elliot began by addressing Mrs. Aston as “Dearest, dearest Margarita” and which included such lines as:

Where can I find language to express the truth, the strength of all I feel towards you? – nay, upon my soul, my ever beloved Margarita, you wrong me when you suspect me of having outlived the loss of the smallest particle of my attachment. I love you to distraction!

The letters go on to convey Elliot’s frustration with Mrs. Aston over her unwillingness to leave her husband and elope with him. He writes:

Oh! My heavenly Margy, I am as I was, and shall always remain so. Loving you as I do had become painful, from your continuing to delay a step on which the happiness of my future life depended; not only to delay, but even to find excuses for not accomplishing it at all. This, and this only, had determined me to drive headlong into the sea of dissipation; for my only resource was the absorption of calm feeling, which hard drinking produces, to forget all because I was forgot by one.

Within the letters, Elliot also reveals the plans of his friends and family members, specifically his cousins Lord Minto and Lord Auckland, to remove him from Mrs. Aston’s sphere of influence, writing: “There is one circumstance I cannot hide from you. I have often told you how severe my friends were with me about remaining infatuated (as they term it) with the beloved of my soul; and they now desire my immediate removal to the East Indies, as the only step that can cure me of my madness.”

Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 2nd Earl of Minto, 1850.

Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 2nd Earl of Minto, 1850.

George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland, 1849.

George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland, 1849.

Elliot ultimately succumbed to the continued pressure of his friends and relations. At the time of the trial, a February 28, 1818 edition of the Huntingdon, Peterborough, and Bedford Gazette reports that he was on the verge of leaving the country, stating: “Captain Elliott is waiting for a fair wind, when he will sail for the East Indies.”

The Case for the Defense

With so much damning evidence, it seemed as if the result of the trial was a foregone conclusion. And perhaps it may have been, had not Edward Elliot engaged James Scarlett, one of the most formidable lawyers in England, to defend him. In Scarlett’s opening statement, he declared that:

He never rose under a heavier impression of the importance of the case which he had to address the Jury upon than on the present occasion, when a gentleman in the situation of the present plaintiff, a gentleman possessing an estate of £15,000 or £16,000 a year, sought to obtain a verdict against the defendant, a youth not yet of age.

James Scarlett, 1st Baron Abinger, 1836

James Scarlett, 1st Baron Abinger, 1836

Scarlett went on to state that he would show the court that Aston’s action against Elliot was “nothing less than a conspiracy” against Margarita Aston, “commenced and carried on for the purpose of getting a separation from her.” Reporting his speech, the Westmoreland Gazette writes:

He would call evidence of the highest respectability, who would prove that Mr. Aston had neglected his lady in a manner the most shameful; that it was the subject of conversation in every circle in Paris, as were the amours of Mr. Aston; and now to complete his object of a separation, he had gone to Paris to bring over two French servants to establish the dishonor of his already much-injured wife.

Scarlett proceeded to call witness after witness, managing to paint a very different picture from that presented by the plaintiff’s attorney. Reporting the testimony of one witness, a man by the name of Mr. Ryan, the Westmoreland Gazette states that the witness:

…had frequently seen Mr. Aston in the streets of London in 1815; witness saw him go into a house of ill fame in Oxendon-street in the middle of the day; had seen him walking in the street with mean-looking women, having the appearance of common prostitutes; he had seen him frequently; and at the time he went into a house in Oxendon-street he had a woman of this description with him.

As if this were not mortifying enough for Aston, Scarlett then called Dr. John Robert Home, a respected physician in the army who had previously attended the Duke of Wellington. Reporting the evidence given by Dr. Home, the Westmoreland Gazette writes:

In August, 1816, witness, by desire of Lady Sidney Smith, went to see Mrs. Aston; found her harbouring under a certain disease, and suffering dreadfully from the effects of mercury which had been administered to her. Witness saw Mr. Aston on the subject, who expressed his regret for what had occurred, and acknowledged the share he had in occasioning it; witness thought she had been ill for some time, and witness advised the taking a house at Passey for the restoration of her health.

It should be noted that during the early 19th century, before the advent of antibiotics, mercury was the common treatment for syphilis. Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease, the side effects of which can include skin ulcerations, heart disease, nerve and brain damage, blindness, and even death. The side effects of mercury were also quite distressing, with some medical texts comparing its effects on the body to that of arsenic.

The Verdict and Aftermath

After the last witness was cross-examined, the judge addressed the jury. He informed them that, despite Aston’s demand for £10,000, “the case was not one for heavy damages.” He then stated that it was up to them to decide “what could be a fair compensation to such a husband for such an injury.”

After only a few minutes of deliberation, the jury found for the plaintiff, awarding damages in the amount of one hundred pounds.

The “trifling” sum of the award did nothing to quell the public’s fascination with the case. Some enterprising individuals even saw a means of making money off of the scandal, with one publisher advertising booklets containing all of the evidence from the trial – as well as the love letters and other “curious particulars”—for only one shilling.

Morning Chronicle , London, England, December 19, 1818. (© 2015 British Newspaper Archive)

Morning Chronicle , London, England, December 19, 1818. (© 2015 British Newspaper Archive)

Colonel Harvey Aston

The disclosures made during the trial about Colonel Aston’s behavior were printed in all of the newspapers. Many reporters happily editorialized, referring to Aston as “dissipated” and stating that “Mrs. Aston’s health had been affected by his depravity.”

Before the trial, Aston had moved in the most elevated society. He was often in attendance at the parties given by the celebrated Regency hostess Jane Harley, Countess of Oxford, at her home in St. James’s Square. In anticipation of a divorce from his wife, Aston had turned his eye to Lady Oxford’s daughters, with special attention paid to her second daughter, Lady Charlotte.

Lady Charlotte Mary Bacon, née Harley, as Ianthe by R. Westall, 1833

Lady Charlotte Mary Bacon, née Harley, as Ianthe by R. Westall, 1833

Lady Charlotte Harley (to whom, under the nickname of “Ianthe,” Lord Byron dedicated the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage) was a renowned society beauty. It was rumored that it was Aston’s desire to marry her that had precipitated his criminal conversation action against Elliot—which some believed was an ill-fated attempt to free himself from a wife he no longer wanted. The March 12, 1821 edition of the Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser explains:

[He had] long entertained sentiments towards her [Lady Charlotte], which he confidently hoped the separation which he anticipated between himself and her whom he no longer regarded as his wife, would soon enable him honourably to declare. The event of the trial, however, and the disclosures which were then made, led to a belief that a divorce could not be obtained in the House of Lords.

Aston’s inability to obtain a divorce from his wife had no impact on his pursuit of Lady Charlotte. He continued his addresses until, at length, his intentions could no longer be hidden from her disapproving family. Shocked to discover that Lady Charlotte returned Aston’s feelings, the Countess of Oxford immediately made plans to remove her daughter from England and “…if possible, by a change of scene, to wean her daughter from an attachment which, under existing circumstances, it became criminal to entertain.”

Jane Harley, Countess of Oxford by John Hoppner, 1797.

Jane Harley, Countess of Oxford by John Hoppner, 1797.

The Countess of Oxford and her daughters traveled to the Continent and, after touring “all that was worthy of remark,” made their way to Italy. There, at Genoa, they were “unhappily joined” by Aston, who immediately resumed his attentions toward Lady Charlotte. The Cumberland Pacquet reports:

On the 28th instant, he prevailed upon the young lady, to whom, in private, he still urged his suit, with the madness of a lover, to elope with him; and they accordingly set out towards Alexandria. The unhappy parent soon discovered what had occurred, and instantly set out with her younger daughter in pursuit of the fugitives, whom she happily overtook at Alexandria, and there prevailed on them to return with her to Genoa.

After the recovery of her daughter, Lady Oxford barred Aston from any further contact with her family. According to some newspapers, this turn of events was so distressing to Aston that, the very next day, he had a fit of apoplexy and died. Other reports were not so certain that had been the case, with some papers stating that he may have poisoned himself or even blown his brains out. In Lady Arbuthnot’s Journal (1820-1832), Harriet Arbuthnot mentions Aston’s death, writing:

There has been a terrible story of Mr. Harvey Aston, who had poisoned himself at Genoa. The first story we heard was that he had seduced two of Lord Oxford’s daughters, who were both with child, & that in consequence of the exposure & shame he had poisoned himself. We have since heard that he poisoned himself from jealousy of Lady Charlotte, who was flirting with a Mr. Clive; but that, she having consented to go off with him, he took an antidote.

An 1822 edition of the Annual Register also reports the rumors, stating, “Various and contradictory accounts have of late been given of an occurrence sufficiently disastrous. It was announced at first as connected with circumstances of peculiar and atrocious guilt involving the seduction and pregnancy of two sisters, nobly related, by an individual of noble family also, who, upon detection, immediately blew his brains out. Next it was said, that only one of the sisters had fallen a victim to his arts, and that the seducer had poisoned himself.”

The Annual Register goes on to produce a letter from the English consul at Genoa, which asserts that “neither pistol nor poison was employed” and that Aston did, in fact, die of apoplexy the day after Lady Oxford thwarted his elopement with her daughter. Aston’s body was embalmed and sealed in lead in preparation for shipment back to England, where he had expressed a wish to be buried.

Summing up his life and death, an 1821 edition of John Bull titles the whole a “Melancholy Affair,” writing: “Few things have occurred which have more deeply interested us than the dreadful death of Mr. Harvey Aston.—It seems as if a fate hung over the name—and we grieve, if possible, the more, because we dare not lament him who is gone.”

Margarita Aston

At the time of the trial, Mrs. Aston had left the family home and was living in a street near Manchester Square. There is little information to be found on what became of her after the trial. What I can tell you is that after the requisite mourning period for Mr. Aston, Mrs. Aston did remarry. A May 13, 1823 edition of the Chester Courant reports that she was married at Paris to a Russian nobleman named Baron Peggenfohl.

Chester Courant, Cheshire, England, May 13, 1823. (© 2015 British Newspaper Archive)

Chester Courant, Cheshire, England, May 13, 1823. (© 2015 British Newspaper Archive)

Captain Edward Elliot

Despite a broken heart and a forced removal to foreign shores, Edward Elliot had what is, perhaps, the happiest ending to this scandalous story. He married Isabella Hardie, daughter of Commander Hardie, and together they had several children, one of whom grew up to distinguish himself in the Indian government.

Edward Elliot lived a long life, presumably in India. He died in 1866 at the age of seventy.

European lady and her family attended by an ayah. The costume and customs of modern India, 1824. (Image via Britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk).

European lady and her family attended by an ayah. The costume and customs of modern India, 1824. (Image via Britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk).

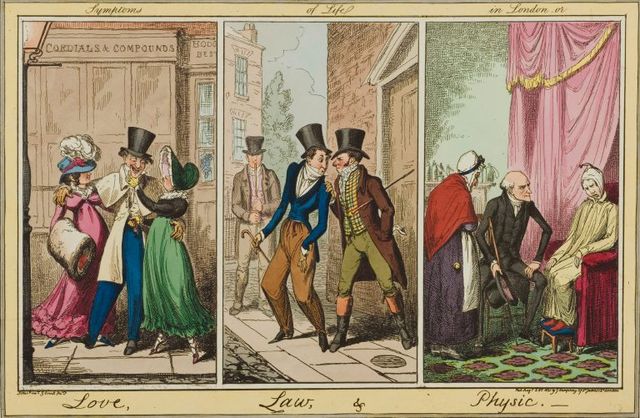

Top photo: Symptoms of Life in London, or Love, Law, and Physic by George Cruikshank, 1821. (Image via Wellcome Library.)

This post originally appeared on MimiMatthews.com and is reprinted here with permission.

More from BUST

Here’s How Fashionable Women Dressed In The 1820s

Victorian Views On Marrying A Scoundrel

This 19th Century Advice For Young Husbands Is A Reminder Of The Bad Old Days