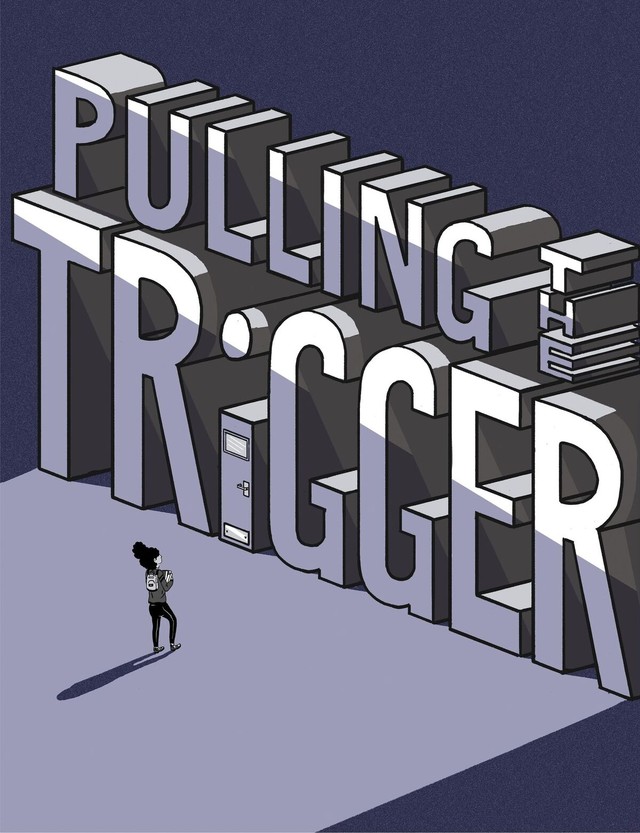

“Trigger warnings” are popping up on college campuses all over America. But do they do more harm than good?

This past summer, the University of Chicago sent out a Dean’s Letter that its students actually read. In it, Dean John Ellison wrote, “Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.” Responses were mixed and impassioned, and reverberated far beyond the student body. Articles discussing the needlessness or necessity of trigger warnings in academia soon appeared in every corner of the Internet. And while the University of Chicago letter may have caused the biggest reaction, it wasn’t the first institution to find itself at the center of a media maelstrom around this issue—Harvard, Columbia, and Oxford are just a few of the universities that have also found themselves embroiled in the debate.

As a result, over the past three years or so, trigger warnings have become the thinkpiece topic du jour. Slate proclaimed 2013 “The Year of the Trigger Warning,” but it was only just the beginning. A 2015 Atlantic cover story came down hard against trigger warnings with their article, “The Coddling of the American Mind.” Later that year, The New York Times published an op-ed by a Cornell professor titled, “Why I Use Trigger Warnings.” The popular Twitter account @thinkpiecebot, which automatically tweets out parody thinkpiece titles, offers these suggestions: “Move Over, Trigger Warnings, ‘Cool Ranch’ Dorito Tacos Are Back” and “Have Trigger Warnings Jumped The Shark?”

But for all this talk about trigger warnings, there’s still some confusion as to what they really are, and what they do, or don’t do, to help or hurt students who have experienced trauma. In fact, to really understand trigger warnings, you have to start by looking at the lives of people born in the ’90s—the 1890s. That’s right; not millennials, but the Lost Generation. That’s because our modern-day understanding of triggers has its roots in WWI, when soldiers who returned from the trenches started exhibiting symptoms including “loss of memory, insomnia, terrifying dreams, pain, and emotional instability,” prompting psychologists to coin the terms “shell shock” and “war neurosis.”

Our understanding of “shell shock” continued to develop through the subsequent decades’ wars, and after Vietnam, psychologists began using the term “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” (PTSD) to describe the condition. PTSD was officially recognized by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980, and these days, psychologists acknowledge that veterans aren’t the only ones who experience it. The National Institute of Mental Health lists not only war, but also physical and sexual assault, abuse, accidents, disasters, and “other serious events” as potential causes. About 10 percent of women and 4 percent of men will develop PTSD at some point in their lives, making PTSD, and by extension, trigger warnings, a primarily female issue.

According to the National Center for PTSD, a “trigger” has a very specific definition: a sight, sound, or smell “that causes you to relive the event.” Some triggers can seem obvious, while others can be completely unexpected. Lucy Pick, Interim Director of the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality at the University of Chicago, explains, “Sufferers of PTSD who might turn up in my classroom include, for instance, war veterans or rape survivors. The things that trigger them may or may not be obvious. For a veteran, it might not be the World War II video I show, it might be a loud noise in the next classroom. For the rape survivor, it might not be a depiction of rape in a play we read, it might be the particular shade of blue I am wearing. For these students, a trigger warning—when that is the most appropriate way to accommodate their disability—is simply a question of providing them with equal access to education.”

Since these types of specific triggers are highly individualized, providing trigger warnings for a student diagnosed with PTSD is usually only an option if the educator is informed ahead of time about their special needs. Erika D. Price, a Chicago-based psychology professor and writer, addresses this by handing out a worksheet to students, on the first day of class, that asks for nicknames, student ID numbers, preferred pronouns, and if students need trigger warnings or other accommodations. Price says that this method of approaching trigger warnings is especially important because students who want trigger warnings can be reluctant to ask for them if they’re not offered. “Students are generally not going to self disclose mental health stuff unless they feel completely safe with that professor,” Price says. “And I know that because so many of my students say, ‘I can’t tell my other professors this but I can tell you because you’ve made it clear that it’s OK to talk about this with you.’” About “10 percent or less” of students want trigger warnings, requesting them for both expected subjects (like rape) and unexpected ones (like apples), and the rest don’t care either way, Price says. “Students just go with the flow. I’ve never had students say anything disparaging or even roll their eyes at the trigger warning thing.”

Many students who request trigger warnings do so because they feel a warning will make navigating their classes a little easier in the wake of trauma. Danielle Corcione, 23, who graduated from the Ramapo College of New Jersey in 2015, says that during a class in which each student was asked to deliver a speech, the first student chose to speak on the topic “anti-suicide.” “Her uncle had killed himself, and she felt that he was selfish to do so,” Corcione says. “My mother attempted suicide countless times when I was growing up. Everything flooded back. I spaced out until my professor called on me to set up my presentation. Being in that situation, I was already incredibly anxious to make a speech—and now I had the weight of my mother’s suicide attempts on my shoulders.” After class, Corcione says, she approached her professor, but “she wasn’t receptive to how I felt at all.” She adds, “If there was a trigger warning, I wouldn’t have sat through the presentation. I wouldn’t have seen my mother in the presentation. I would’ve done a better job at presenting my speech. I would’ve been a better student.”

While these requests sound reasonable, the uproar around “trigger warnings” in academia isn’t about these highly personalized PTSD triggers at all. Instead, it’s about the insistence that warnings precede any content that is commonly viewed as disturbing, particularly to women—the rape scene in the play, not the professor’s blue shirt, to use Pick’s example. Pick defines this type of trigger warning as “blanket warnings to groups of individuals that they are about to encounter material that many people would find difficult and disturbing.” In history or literature classes, for instance, issues such as mental illness, suicide, rape, domestic violence, child abuse, or other troubling subjects inevitably arise, and increasingly, students are asking for trigger warnings before such topics are discussed.

“If there was a trigger warning, I wouldn’t have sat through the presentation. I wouldn’t have seen my mother in the presentation. I would’ve done a better job at presenting my speech. I would’ve been a better student.”

This broader use of the term “trigger warning” is a relatively recent phenomenon, and was either started by or boosted into common usage by the feminist Internet. In a 2014 interview, Bitch cofounder Andi Zeisler recalled first seeing the term prior to a discussion about sexual assault on Ms. magazine’s online community forum “in the late ’90s.” By the early 2000s, trigger warnings had also spread to LiveJournal, and were used to warn about a wider range of content, including self-harm, eating disorders, and addiction. In recent years, however, warnings have begun appearing before online discussions not necessarily linked to trauma or addiction, but rather, before difficult, scary, or controversial subject matter. A quick search of the term “trigger warning” on Tumblr comes up with these results: a GIF of the character Princess Mononoke wiping blood off her face is tagged with a trigger warning for blood; a doodle of a spooky circus clown is tagged with a trigger warning for clowns; a meme comparing Donald Trump to Hitler is tagged with a trigger warning for Nazism; photos of a spider killing a fly contain a trigger warning for animal death.

When trigger warnings made the jump from online forums to classroom settings, controversy erupted over whether the students demanding warnings were being helped or educationally stunted by their use. In actual practice, many advocates for academic trigger warnings say they can be as helpfully unobtrusive as an R-rating at a movie or an “explicit content” label on an album. “I think people misinterpret trigger warnings as people actually shouting ‘TRIGGER WARNING!’ before every single class, or completely skipping over real world knowledge that should be taught because of ‘sensitivity,’ but that’s not the case,” says 2014 Kent State graduate Hilary Crisan, 24. “We already have trigger warnings in our everyday lives, it’s just that no one really notices. Before television shows like It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia or American Horror Story begin, a screen comes up saying that the show is rated ‘mature’ for swearing, sexual images, graphic images, and so on.”

Despite the ubiquity of trigger warnings in pop culture, however, there are students who see them as counterproductive in an academic setting. Marcellina Chappelle, 22, says she’s glad she didn’t have the option for trigger warnings while attending high school in New Jersey. She recalls being assigned the book Kaffir Boy: The True Story of a Black Youth’s Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa by Mark Mathabane when she was a teenager, and being particularly disturbed by a chapter in which Mathabane’s father forces him to undergo circumcision. “Knowing myself, when I was in high school, if I had been given a trigger warning, I would have definitely skipped that chapter,” she says. Chappelle adds that, in high school, she learned to deal with traumatic content without trigger warnings, and she’s glad to have had that experience. “Having lost a parent, there were times when I would get overwhelmed or upset about something that was going on in class,” she says. “But I learned how to cope. Even if I didn’t say I was upset, I would say, ‘Hey, can I go to the bathroom?’ and I would collect myself.”

Educators are not all on board with trigger warnings, either. Marcie Bianco, a New-York based writer and professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and Hunter College, says she was penalized by administration when a student complained about the lesbian content in Audre Lorde’s Zami, which Bianco taught in her class. “For me, Audre Lorde is one of the greatest public intellectuals in American history,” says Bianco. “This student came in halfway through the semester and ended up with a B+, and I think what happened was she didn’t want the B+, so she took it up with the department and made it about me ‘shoving lesbianism down her throat.’”

For all the discussion about trigger warnings, though, they are relatively rare. According to a National Coalition Against Censorship survey of over 800 college and university educators, only 15 percent of respondents said students had requested trigger warnings in class, and less than 1 percent said their institution had a formal policy on trigger warnings. Despite the rarity, however, the majority of respondents were against them: 62 percent said trigger warnings “have or will have a negative effect on academic freedom,” and only 17 percent viewed them favorably.

Personally, Bianco sees her position against trigger warnings as a feminist one. “As a feminist, I believe in open dialogue, I believe in progress, I believe in social change through dialogue,” she says. “Moving ahead as individuals and as feminists, we have to encounter difficult texts, and I don’t know if trigger warnings enable that. I feel like they prevent dialogue.”

In fact, though trigger warnings are associated with feminism, not all feminists support their use. Roxane Gay, Jessica Valenti, and Jill Filipovic are just a few of the prominent feminists who have published pieces criticizing them. Filipovic comes down the harshest of the three, writing, “Generalized trigger warnings aren’t so much about helping people with PTSD as they are about a certain kind of performative feminism.”

If trigger warnings are in fact just a politically correct “performance,” then it could be argued that they don’t do as much for trauma survivors as other forms of outreach. “As a community, we should all be working toward having a greater understanding of how trauma impacts individuals. Being trauma-informed does not equate simply to having a trigger warning. That isn’t enough,” says Amber Stevenson, an adjunct professor and the Clinical Director of the Sexual Assault Center in Nashville, TN. “Are teachers equipped to assist a student who may be triggered? If a student does need to leave the classroom following a trigger, what implication does that have for a student’s privacy? Who decides when and how to give a ‘trigger warning’?”

“Having lost a parent, there were times when I would get overwhelmed or upset about something that was going on in class. But I learned how to cope.”

Sonya Norman, Consultation Program Director at the National Center for PTSD and Associate Psychiatry Professor at the University of California, San Diego, agrees with Stevenson, saying trigger warnings are well intentioned, “but that isn’t the end of the conversation.” What’s more important, she says, is “creating a day-to-day environment and culture where people can get help when they need it.” They both have a point. Perhaps, instead of focusing so much on trigger warnings, universities should take more comprehensive steps to make classrooms better environments for students. One big step could be educating professors about trauma while working to end mental health stigma.

As for the University of Chicago, well, it turns out that a lot of the faculty doesn’t agree with the Dean’s condescending position on trigger warnings—even if they aren’t personally for them. In a letter signed by over 150 faculty members and published in the student paper, The Chicago Maroon, numerous professors stated that even though they held a “variety of opinions” about trigger warnings, they could agree on one thing: The conversation is worth having, and worth having with respect. “The right to speak up and to make demands is at the very heart of academic freedom and freedom of expression generally,” they wrote. “We deplore any atmosphere of harassment and threat. For just that reason, we encourage the Class of 2020 to speak up loudly and fearlessly.” This is a sentiment that all feminists can surely get behind. Keep speaking up—loudly and fearlessly— whether in support of trigger warnings or against them, until you are satisfied that your voice has been heard and your needs have been addressed.

By Erika W. Smith

illustration by Courtney Menard

image via Wikipedia

More from BUST

Is Trump A Trigger? According To Many Women’s To The 2nd Presidential Debate, The Answer Is Yes

How To Support Someone Who’s Reliving Sexual Assault

Rupi Kaur: ‘What Happens When Your Home, When Your Body, Is Attacked?’