IT’S NOT EVERY day you discover a 17th-century, cross-dressing, duelling, bisexual opera singer. But it happens every few weeks on social media. Someone will post, “Wow! Has anybody heard of Julie d’Aubigny? She’s amazing!” And the cult surrounding this fascinating historical figure grows a little bit bigger.

So who was this remarkable woman?

Mademoiselle de Maupin, also known as Julie d’Aubigny, was one of the stars of the Paris Opera in the age of King Louis XIV—a time of extravagant luxury and even more extravagant fashion. But she’s more famous—and infamous—for her off-stage exploits as a notorious duellist, as a lover of powerful men and women, as a fashion icon who wore men’s clothes and a sword, and for committing the occasional crime. A celebrity throughout her career, which spanned the years from 1690 through 1705, she’s become a symbol of everything from beauty to courage to monstrosity to feminism to queer pride in the centuries since her death in 1707 at age 33.

There are plays about her, at least one ballet, one corny movie (Madamigella di Maupin, 1966), and a French television mini-series (Julie, Chevalier de Maupin, 2004). She’s also been the subject of numerous biographies and several novels—most famously Théophile Gautier’s 1835 fantasy Mademoiselle de Maupin, Julie chevalier de Maupin by Anne-France Dautheville (1995), and my own novel, Goddess, which was released in 2014.

But did all the duels and affairs and outrages attributed to her really happen? I spent five years researching her life, and even I’m not sure how much of her legend is true. But it is so entertaining.

L’escrimeuse (The Swordswoman) by Jean Béraud

L’escrimeuse (The Swordswoman) by Jean Béraud

THE (POSSIBLY) TRUE STORY OF MADEMOISELLE DE MAUPIN

JULIE-ÉMILIE D’AUBIGNY was probably born in 1673, the daughter of Gaston d’Aubigny. He was a secretary to the King’s Horse Master, the Count of Armagnac, a powerful and wealthy courtier. It’s likely she grew up in the Tuileries Palace in Paris and moved to the newly built Versailles with the rest of the court in 1682, when she was 9. At Versailles, the Count ruled over the Grandes Écuries (Great Stables), a complex as big as a palace, with its own brass band, riding schools, and opulent apartments. It was the setting for grand opera performances attended by the entire court, and it was here that Julie’s father trained the young noblemen who would one day become pages at the court.

As an accomplished swordsman himself and a former musketeer, Gaston trained his only child alongside the boys, dressing her in male clothes and providing her with access to the schooling and all the skills required of a cavalier: fencing, dancing, riding, singing, drawing, languages, and etiquette. She was surrounded by boys from the aristocratic families of France–at a young age, she could beat them at swordplay, and perhaps outdo their swagger.

She was surrounded by boys from the aristocratic families of France–at a young age, she could beat them at swordplay, and perhaps outdo their swagger.

Around age 14, Julie, now considered a beauty, became the Count’s mistress. One of the first biographical accounts of her life, by the Parfaict brothers in their 1756 Dictionnaire des Théâtres de Paris, describes her this way: “Mlle Maupin was not very tall, but she was very pretty: she had chestnut hair, almost fair and beautiful, and big blue eyes, an aquiline nose, a lovely mouth, very white skin, and a perfect throat.”

The Count arranged her marriage to a Monsieur de Maupin, who was dispatched to the provinces, never to be seen again. But Madame de Maupin’s affair with the Count ended when she ran off with her handsome young fencing master, Séranne. Séranne was a commoner like Julie, raised in the south of France and now mingling with the elite. Every day, the city’s fencing halls filled with young aristocrats obsessed with the ancient art of duelling, in spite of King Louis’ regular edicts banning it. Penalties for duelling were severe—from being stripped of one’s title or army commission, to imprisonment, exile, or even execution. Séranne, with his constant duelling and notorious display bouts, infuriated the fearsome police chief, Monsieur de la Reynie. After one fatal duel, Séranne was forced to flee Paris, chased by police, and Julie escaped with him. They rode south on horseback, singing for their supper and dazzling crowds at fairs and in taverns with displays of their sword-fighting skill. Séranne promised her their fortunes would change. He said that in the south, he owned a castle, and his family would welcome her.

But Séranne’s promises were fantasies. Still desperate for money, the couple joined the Marseille Opéra, where audiences fell in love with Julie. This was especially true of the daughter of a local merchant, who watched from the balcony as this graceful, beautiful singer astonished the audience. The two young women fell so publicly in love that the girl’s horrified family hid her away in a convent in Avignon, committing her to a life of chastity. But a desperate Julie followed, joining the order as a lay sister.

Her life in the cloisters, however, didn’t last long. One night, the couple staged a dramatic escape. An elderly nun had died, so Julie placed the corpse in her young lover’s cell as a decoy, set fire to the building, and the two of them fled during the mayhem.

They were on the run across Provence for three months, during which time Julie was tried in absentia on charges of kidnapping, body snatching, and arson. The authorities couldn’t quite bring themselves to admit that a woman might commit such crimes, so the edict sentencing her to death at the stake was proclaimed using the title “Monsieur” d’Aubigny. The runaways were hunted across the south of France, but their luck eventually ran out. Julie’s beloved was captured and bundled off to a more impregnable convent, and Julie continued her cross-country fugitive adventure alone. The two girls never saw each other again, and the affair was so effectively hushed up, historians today still don’t even know the name of the young woman from Marseille who stole Julie’s heart.

Mademoiselle de Maupin by Aubrey Beardsley, 1898

Mademoiselle de Maupin by Aubrey Beardsley, 1898

A few weeks after the pair’s separation, as Julie rested at an inn, a group of young noblemen decided to make trouble. Insults flew, and one of the men challenged Julie to a duel. He was convinced of his own superior skill with the sword, and since she was wearing men’s clothes, he didn’t realize at first that his competitor was a woman. Julie beat him easily, wounding him. After the duel, she discovered that he was Count Louis-Joseph d’Albert de Luynes, the darling son of the most powerful family in the country. D’Albert was astonished enough to have been beaten, let alone by a woman, and refused to be nursed back to health by anyone but her. They became lovers, and later friends for life.

But Julie grew bored with d’Albert, so she rode off again, determined to become a famous singer, not just another nobleman’s mistress. She trained with an old actor, Maréchal, and then paired up with an ambitious young baritone, Gabriel-Vincent Thévenard, and together, they headed for Paris. On her first day back in the city, Julie visited her former lover, the Count of Armagnac, to convince him to arrange a pardon from the King for her crimes in Provence. Meanwhile, Thévenard auditioned for the Paris Opéra and was hired immediately, on the condition that Julie would be hired, too.

That was how, at age 17, Julie became a member of one of the world’s greatest musical companies. She made her Paris debut in sensational style in 1690, as Pallas Athéne in Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione, and went on to appear in many of the Opéra’s major productions. She became “La Maupin.” A star.

Many, but probably not all, of her performances on stage are known through cast lists, gazettes, and opera company records, proving she was, above all else, a performer. A journal entry by the Marquis de Dangeau noted: “The King, who had not seen anything of the kind for some considerable time, seemed to take considerable pleasure. Madame de Maintenon was also present for a time and heard La Maupin, who has the loveliest voice in the world.”

But this outrageously queer, cross-dressing woman was never one to settle down. One night she attended a court ball in men’s clothes and kissed a young woman on the dance floor. Three noblemen challenged her to a duel for insulting the woman, who, for all we know, might not have minded a bit. But a challenge is a challenge, so Julie told each of the men she would meet him later that evening. One of her later biographers, Cameron Rogers, describes it like scene from The Three Musketeers:

The blades rang each on each and the heels of the duelists pounded sharply in the still night. The darkness lightened an instant as a timorous moon appeared…and La Maupin, parrying, spoke clearly. “This time I’ve had enough….” A masterly riposte [fencing attack] and her opponent collapsed upon his knees. The second cockerel was on her in an instant but the combat was brief. The moon peeped again and she marked her man against a wall. “Ha! Now that I’ve seen you, farewell.” He fell, pierced through the shoulder. Startled, the last of her enemies fenced carefully and with calm, but a feint followed by a thrust…undid him…as he stumbled. “The contrary would have surprised me,” observed the Amazon and returned to the ball.

Julie fled Paris again, to avoid the King’s harsh penalties for duelling, but this time she ended up in Brussels, where she began a tumultuous affair with Maximilian Emmanuel, the Elector of Bavaria (a position similar to a modern-day governor). Maximilian had an eye for the ladies, and in a jealous rage one night, Julie stabbed herself on stage with a dagger. But her theatrics backfired— Maximilian offered her 40,000 francs to leave him in peace. She threw the coins at his emissary and returned to Paris.

Perpetually well connected, Julie was pardoned upon her return to France for her latest duelling dalliance, this time through the intervention of the King’s brother, the Duke of Orléans. Shortly thereafter, in 1698, she returned to the Paris stage as Minerve in Lully’s Thésée, and then in Campra’s Tancrède, singing a piece written especially for her voice.

Mademoiselle Maupin de l’Opéra, c. 1700

Mademoiselle Maupin de l’Opéra, c. 1700

Madame la Marquise de Florensac by Robert Bonnart, 1694

Madame la Marquise de Florensac by Robert Bonnart, 1694

One of the stories told about Julie during this phase of her career involved her assault upon the singer Louis Gaulard Duménil, a performer who she knew had been fondling the Opéra’s chorus girls backstage. Historians Joseph de La Porte and J.M.B. Clément, in their 1775 book Anecdotes Dramatiques, presented the altercation this way:

She waited one night, dressed as a cavalier, in the Place des Victoires, and wanted him to take his sword in hand. On his refusal, she gave him a caning, and took his watch and snuffbox. Duménil ventured the next day to tell his story to the opera, but he dissembled entirely. He said that three robbers had fallen upon him, he had defended himself against them for some time but, despite his resistance, they had taken his watch and his snuffbox. “You are lying shamelessly!” said Maupin, who had been listening, ‘‘You were challenged by only one person and that person is me: here is proof.” She pulled out the watch & snuffbox and she gave them to him, calling him a coward and poltroon. Duménil did not stop to question, and prudently retired.

But the height of Julie’s fame wasn’t all fun and games and caning poltroons. She suffered bouts of despair, unrequited love, and serious violence—once ending up in court for beating her landlord, and on another occasion, threatening to blow the Duchess of Luxembourg’s brains out.

Throughout Julie’s many heroic and sometimes pathetic adventures, the crowds adored her—either in spite of or because of her high-profile affairs with women, her brawling and duelling, and her breeches and sword.

In 1703, Julie fell in love with Madame la Marquise de Florensac—a woman who was wealthy, well connected, and considered by many to be the most beautiful lady in France. As biographer Gabriel Letainturier-Fradin wrote in 1904:

“For two years they dwelt in such affection they believed to be perfect, ethereal, and beyond reach of the contamination of men; the young women isolated themselves, enamoured, only appearing in public at occasions where their presence was essential.”

When the de Florensac died of a fever in 1705, he wrote, “the pain of La Maupin was boundless.”

Distraught after the loss of de Florensac, Julie retired from the opera and never performed again. Bereft, she entered a convent where she died in 1707 at the age of only 33. Many of her biographers write that she died of a broken heart, and that might even be true.

La Maupin is one of those extraordinary people who continually surprises new generations, and whose life story bubbles up into view at times like these, when society’s ideas about gender and sexuality are in flux. Even if half of these stories are true, it’s little wonder that such an infamous and dramatic figure loomed large in the minds of her contemporaries, and has found a way to remain in popular culture ever since.

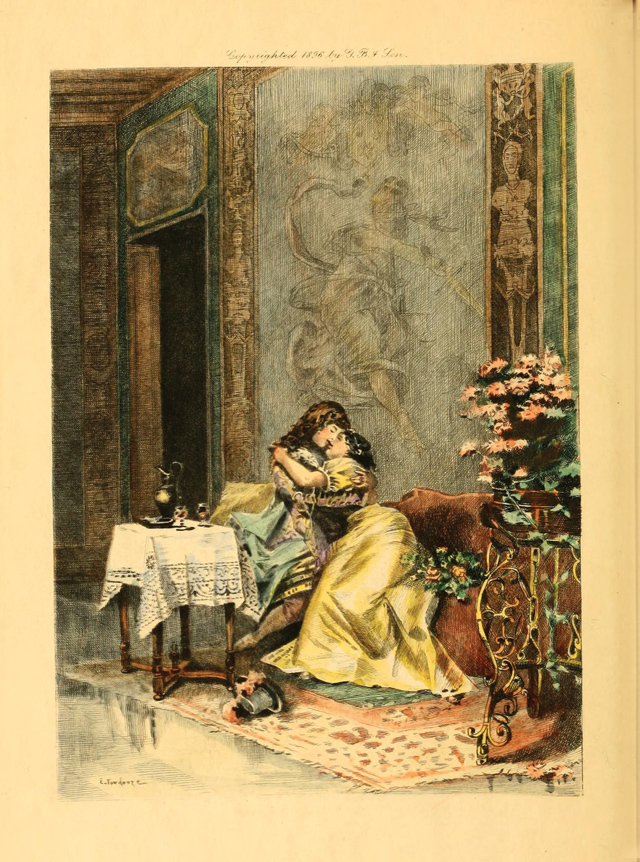

Illustration from Mademoiselle de Maupin Volume II by Théophile Gautier, 1897, etching by Francois-Xavier Le Sueur and drawing by Édouard Toudouze

Illustration from Mademoiselle de Maupin Volume II by Théophile Gautier, 1897, etching by Francois-Xavier Le Sueur and drawing by Édouard Toudouze

By Kelly Gardiner

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2020 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

How The Once Enslaved “Stagecoach Mary” Became The Gun-Toting First Black Woman Mail Carrier

A Brief History Of Flappers, Some Of The Original Rule-Breakers

The Legacy Of Clara Bow, America’s First Sex Symbol