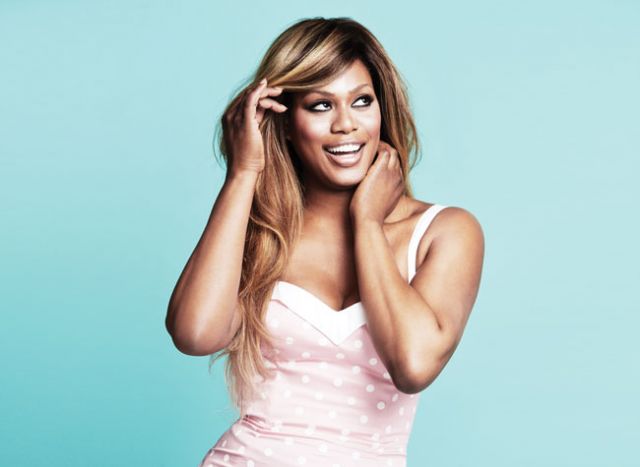

Orange is the New Black ’s Laverne Cox is an accomplished actress, outspoken trans-rights activist, and boundary-busting sex symbol whose unique pop-culture platform is helping her change the world.

I’VE INTERVIEWED A few celebrities in my day, but Laverne Cox is the first to mention “cis-normative, hetero-normative, imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy” within the first ten minutes. Or, you know, at all. By the time we’re done chatting in N.Y.C., I’m convinced that this actress, advocate, artist, thinker, producer, college speaker, “bell hooks-a-phile,” karaoke-slayer (more about that later) and trained dancer ought to add “intellectual badass” to her business card. Because while I entered our meeting as a starstruck fangirl, I left feeling like I’d been taken to church, school, and possibly intersectional feminist heaven. Quite plainly, the woman is a fucking whirlwind of smarts, beauty, and guts.

“Three or four years ago I could barely pay my rent,” the Emmy-nominated star of Netflix’s hit show Orange is the New Black tells me over lavender mint tea. “So it’s nice to be in demand.” We’re sitting in a well-appointed, quiet two-story restaurant with bookshelves from floor to ceiling. When the Alabama-raised actress takes off her sunglasses and hood—a standard-issue celebrity disguise that looks incredibly chic on her—she seems a little sleepy. She’s just finished a speaking tour of Ontario; shot a CBS pilot; and is gearing up to do press for the third season of OITNB. “In demand” seems like the understatement of the year.

Cox warms up quickly as we delve into the topics that seem closest to her heart: art and advocacy. The transgender actress, an alum of the Alabama School of Fine Arts and Marymount Manhattan College, plays inmate Sophia Burset on OITNB. She received a historic Emmy nomination for her performance, but her career doesn’t stop there. I tell her I’ve never seen a speaking schedule as rigorous as hers is—in one recent month, she crisscrossed the states speaking at six different universities from Connecticut to California—and wonder how she balances her passion for acting with her obvious dedication to trans advocacy. “I’m an actress first and always an actress first,” she says. “I have to prioritize that work. At the end of the day, most of what I do in terms of advocacy is talking. I talk a lot. I’ve also been involved in elevating some trans people’s stories that maybe didn’t have the same platform that I’ve had, and I’m proud of that.”

To that end, Cox is a major creative force behind Free CeCe, a documentary about transgender woman CeCe McDonald, who served time in a men’s prison in Minnesota. The film, expected to debut in 2016, focuses on trans-misogyny and violence against transgender women of color.

“I had this fantasy that once I was famous and accepted by society, this guy would be like, ‘Oh, I’m dating Laverne.’”

“I love CeCe,” Cox says. “Her case came to me because violence against trans women has always been something that hits me in my gut.” Cox is not unfamiliar with physical and emotional violence. “I think ‘bullying’ is almost a nice word for being beat up, held down, and kicked by groups of kids. ‘Bullying’ makes it all sound nice when it’s straight up violence. So I have a history. I’ve dealt with a lot of street harassment, so violence against trans women is something that’s terrifying.” And then Cox asks the question central to her work as both an advocate and an artist: “How do we really begin to dismantle a culture of violence, of rape culture? What does that look like?”

This is the point where Cox mentions what feminist author bell hooks calls “imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy” and says she amends it to include “cis-normative and hetero-normative.” It isn’t the only time she mentions hooks, a longtime influence, and I bring up a conversation the two had onstage at The New School in the fall of 2014. The women agreed on much, but hooks called into question Cox’s presentation of femininity—how her long blond wigs, dresses, and traditional feminine beauty embody what some feminist women have attempted to reject or avoid. Onstage, Cox responded in part, “If I’m embracing a patriarchal gaze with this presentation, it’s the way that I’ve found something that feels empowering…I’ve never been interested in being invisible and erased.”

Cox, who remains in touch with hooks, tells me “everybody” asks her about that exchange. I ask her if it’s insulting to suggest that her high-femme presentation is, in fact, a capitulation to the patriarchy rather than an empowered choice, and she responds carefully. “What bell hooks would say to that is that we make choices—and this is me being a huge fan of bell hooks—but there’s something almost binary that suggests either you are moving against cis-normative, hetero-normative, imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy, or you are complicit with it. That kind of binary is really, deeply problematic. I think it’s more complicated. I’ve gone through all sorts of aesthetic phases. I had a shaved head in college. I wore makeup and I was gender-nonconformist. I also had box braids and a mohawk in college and a little bit after. So I’ve gone through all these different phases aesthetically. I love where I’m at now. I feel like I’ve evolved into being more myself.” But, she adds, “I think at the end of the day, I am very much working within the system.”

She contrasts her own experience with that of her twin brother, the noted musician, composer, singer, and multimedia artist M. Lamar, who played a pre-transition Sophia on OITNB (and who first introduced Cox to the work of bell hooks). While he’s received critical acclaim in such esteemed outlets as The New York Times, particularly for his 2014 multimedia gallery piece Negrogothic, a Manifesto, the Aesthetics of M. Lamar, Cox says outsider work like Lamar’s, “rarely transfers to financial stability.” She muses about this difference between their work and where it has taken them. “Even though there’s something about me that isn’t fully mainstream, there’s something about the choices I’ve made that exists within a system more so than other people.” I get the sense she doesn’t think this is particularly fair. I also begin to realize that while Cox is giving me a lot of answers, she also spends a lot of time asking questions—of herself, of the culture in which she finds herself, and of the world at large.

“What I like to say to the world is that men are just as hurt by patriarchy as women are.”

We talk about the task of being the Laverne Cox: the advocate, the actress, the star of creator Jenji Kohan’s women-in-prison magnum opus. I ask what it’s like to have every element of her being analyzed because of what she represents. Everything from her hair to her career to…. “To my basic humanity and gender?” she interjects.

“Yeah,” I say. “Your right to exist. Your lipstick. Everything.”

“That’s how patriarchy works,” she says. “We are all constantly scrutinized based on aesthetics and appearance and judged on that stuff. I think that’s part of being a woman. It’s a part of being an actress on a popular TV show—thank God. I’m grateful for that. It’s a lot of spiritual work for me as I deal with and figure out how to be a famous person who’s recognized. A lot of my work is to stay grounded, is to stay spiritual. It is to disconnect from what other people say about me, but also to try and be connected to the joy and the love. I think this is where I’m struggling now.”

This reminds me of something Cox posted on Instagram recently. It was an image from her recent trip to Canada, with a caption that read in part, “I am not always open to receive all this love. Sometimes it’s too much. I feel so grateful to be open today.” I ask her about it—the simultaneous openness and resistance to adulation from strangers. “This week, I allowed myself to be open and really present with it, which I’m not always able to do because I’m distracted,” she says. “Because I think when you let in the good stuff, then the bad stuff is going to come in, too.”

She grins and adds, “I feel like Mariah Carey when she talks about how her fans make her feel better. It’s almost corny to say that, but it’s the truth. Yet in an airport or on the street, I’m not always able to receive that. As much as I love and am grateful for my fans and supporters, I have to set boundaries with them. I have to set boundaries with everybody.”

Actually, she may well be an idol of Mariah-like stature to the rabidly devoted fan base of OITNB. Cox calls the show “a gift” and says with evident amazement, “It’s like, who gets famous just from one show?” “The characters are so nuanced and so profoundly human,” she says, “which is a gift from Jenji Kohan and all of our writers. She discovered so much unknown talent—like Uzo Aduba, Samira Wiley, Danielle Brooks, Yael Stone. There’s just all of these amazing actors who no one knew about until this show, who are brilliant.”

I ask Cox if her character, Sophia, who has undergone genital reconstructive surgery and hormone therapy, would actually be placed in a women’s prison in real life. Cox explains that in many states, the decision of where to house a trans person in the correctional system is based exclusively on surgical status. Which brings us to our culture’s obsession with genitalia, specifically with knowing whether a trans person has had “bottom surgery.” She admits she hasn’t always been immune to that curiosity herself, and recalls a time when she wondered about the surgical status of a friend of a friend. True to form, she used it as an opportunity to critically analyze her own way of thinking. “When we meet someone who is cis-gender or non-transgendered,” she says, “we generally make assumptions about what their bodies are like. But when we meet someone who is trans we can’t do that. So for me in that moment, I got this crazy anxiety and asked the question, ‘What does it mean for us to be able to sit with anxiety?’ A lot of times, we don’t know how to do that.”

In previous interviews, Cox has mentioned that some romantic partners have not introduced her to their families. I wonder if it’s gotten any easier now that she’s achieved professional success. “There’s a man that I was involved with on and off for eight years,” she says. “I never met any of his friends or family. We barely even went out in public together, so that tells you the nature of the relationship. What’s deep to me about that is that I think I had this fantasy that once I was famous and accepted by society, this guy would be like, ‘Oh, I’m dating Laverne. I can show her off now.’ And it’s actually the opposite of that. He’s engaged to someone else now.”

I’m struck by how heartbreaking that must have been, and also by how clear it is that Cox has done the work to deal with and understand it. “What I realized is it’s not about me,” she says. “It’s actually about that man’s shame around being attracted to me. And his own issues of being seen as less of a man. He has deep, deep, deep insecurities. There are many men who date transgender women and who engage with us only sexually and don’t want anyone to know about it. They’re straight identified, and there’s a huge stigma around men who are attracted to and have sex with and date trans women. They’re arguably even more stigmatized than we are.”

“I used to believe that if I was smart enough, if I was good enough, if I were pretty enough, that this man all of a sudden would love me and want to fully integrate me into his life,” she adds. “What I have come to learn is that it does not matter how successful I am, how accomplished I am, how smart I am, how good in bed I am. None of that matters if a man is just not available. I cannot choose those people. I have to choose differently.”

To read the rest out our interview with Laverne, pick up the June/July 2015 issue of BUST Magazine on newsstands now!

By Sara Benincasa Photographed by Danielle Levitt

Styling by Jessica Bobince

Hair by Ursula Stephen @ Starworks Group

Makeup by Deja for DD-Pro using MAC Cosmetics

FASHION CREDITS:

1. DRESS: DEADLY DAMES/PIN UP GIRL CLOTHING

2. SWIMSUIT: ESTHER WILLIAMS/MODCLOTH; SHORTS: H&M

3. SHIRT: MINKPINK/MODCLOTH; SKIRT: MILLY; SHOES: PLEASER

4. SHIRT: MINKPINK/MODCLOTH; SKIRT: MILLY

5. BRA AND SKIRT: MILLY; SHOES: PLEASER

6. DRESS: ALICE’S PIG/MODCLOTH; STYLING ASSISTANCE: ATHENS ANDREWS, CARLOS ACEVEDO, AND EMILY KIRKPATRICK