In the early ’80s, a tough-as-nails, all-female skateboard gang calling themselves “the Hags” became legendary on the streets of West L.A.

By Emily Savage // Photo by Molly Cranna

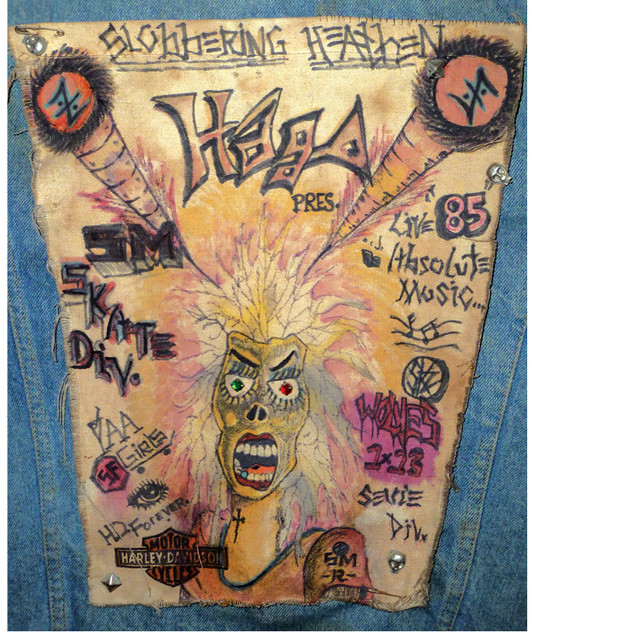

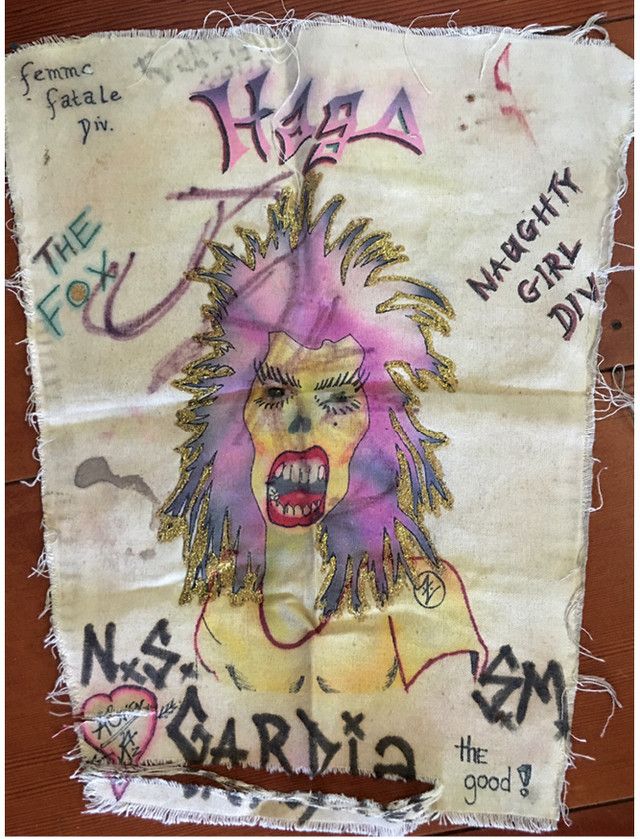

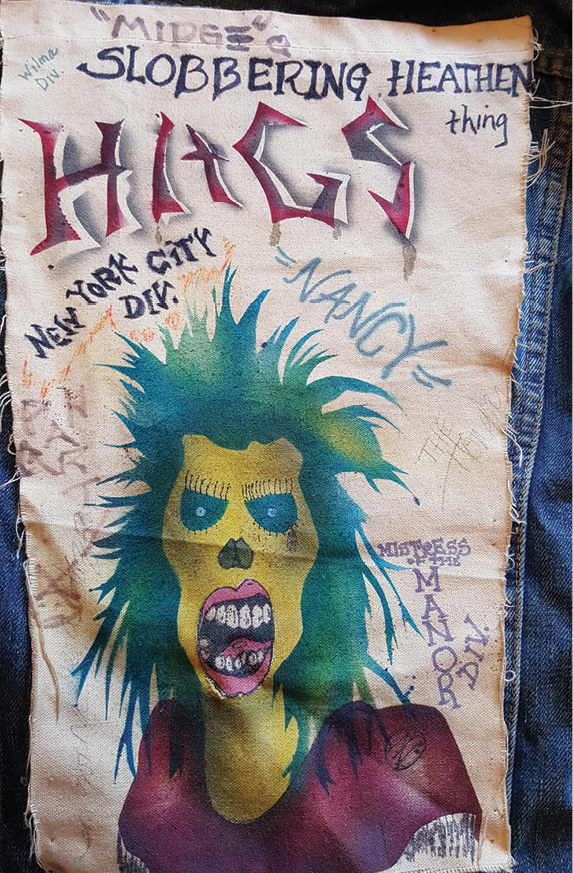

By the time she was in her late teens, Sevie Bates had already been living away from her mother’s Santa Monica home for years. Her life revolved around three things: partying, punk music, and skateboarding. She’d roll up on her board to rock clubs in L.A. sporting bleached-white hair, ripped shirts, a red petticoat over men’s boxers, hand-airbrushed white Converse with zebra stripes, and most importantly, a tattered denim vest with a large piece of airbrushed canvas adorning the back. That patch—featuring a snarling skull with wild, spiky hair—could also be spotted on the backs of about 10 other girls rolling through West L.A. in the early 1980s. They were called “the Hags,” and for a brief moment in time, they were living legends.

Bates started the Hags as an all-girl, punk rock skateboard club in 1983 or ’84 (there’s been some debate), and the canvas patches were the raucous group’s insignia. For about a year or so—certainly less than two—you could spot a Hag by her patch and punk style while passing through the gang’s various beachy hangout spots. Being a Hag meant a tremendous amount to those who were a part of it, and the group even got some media attention at its peak. But they weren’t as well-documented as they would be today.

A bunch of Hags circa 1984 outside Hags HQ (left to right) top: Gardia Fox, Little Kim, Amanda Brix Toland, Elizabeth Devries. Bottom: Sevie Bates, Michel Miller, Keren Sacks

“We were like a gang—and we’d skate around Hollywood Boulevard. Mostly, it was about going to clubs, partying, and drinking,” Bates, 53, tells me as we sit in a living room in Echo Park. “Everything is more fun in groups, and it was good to have the girl power thing.” While she’s now sober and runs her own dog-watching business called Dogs Rule L.A., Bates says she grew up poor, and with a lot of hostility toward her single mom, which led to early drug use and worse. She gives the impression that she’s battled a lot of demons in her life, but has a steely, self-assured presence in person.

The Hags was a longtime dream for Bates. She’d bought her first board in the early ’70s at a Thrifty’s discount store at age 9. It was just a little wooden skateboard called “The Black Knight,” with clay wheels and loose ball bearings. But by her late teens, Bates was an aggressive and talented street skater who frequently got into scuffles in then-crime-ridden Venice Beach, and says she was always pushing back against what was expected of her as a girl. She had a motorcycle, a skateboard, and short hair. She partied hard. On top of all of that, she says she was often looked at curiously because of the large, light-red birthmark that sits on one side of her face. As a reaction to all this and more, she gathered up a crew of women she’d become friendly with and started the Hags. “I had a lot of rage and a lot of aggression, so I didn’t take shit from anyone. That’s what lead me to the Hags,” says Bates.

By the early ’80s, when the idea for the Hags began to take shape, street skating was going through a rebirth of popularity, in part due to the inception of the skateboarding magazine Thrasher, in 1981. This resurgence came after the hobby’s first ’60s wave of popularity, and the more noteworthy ’70s skateboarding explosion that birthed the legendary Zephyr (Z-Boys) skateboard team of Venice and Santa Monica in 1975.

Photo by Molly Cranna

Photo by Molly Cranna

In fact, the girls who would later become the Hags had all been hanging out with Z-Boy skateboarder/musician Tony Alva, his skate team, and other male-dominated skate crews, including the Jaks from San Francisco that had a few scattered members in Venice. One of these future Hags, Keren Sacks aka Raggy, 59, who now lives in the Mojave Desert, moved down the street from Alva when she was in her early 20s. A hairdresser even way back then (she’s now a stylist for Venice Beach’s Paper Scissors Rock salon), Sacks became known for tying different pieces of fabric rags into her silver-gray dreadlocked Mohawk, and Alva used to skate by and yell “Rag Girl!” at her. This is how Sacks ended up with the nickname “Raggy,” a moniker that she would soon be wearing on the back of her vest.

“I remember telling Tony, ‘I should be in the Jaks, because I can skate better than a lot of these guys,’” says Bates. “It pissed me off. It was a dude thing, like a motorcycle club.” Shortly after she was denied entry to the Jaks, Bates came up with the name “the Hags,” started recruiting her friends, and got to work making their signature back patches. Bates says she doesn’t quite remember where the Hags name came from, but that some members had suggested “the Jills” as a response to the Jaks, and she didn’t like that. “I think [calling us the Hags] came from my subconscious,” she says.

The Hags flashing their “colors”

Bates officially launched the Hags when she created club patches for 9 or 10 of her friends so they could all go out skating together in uniform. Former Hag Michel Miller, 53, who met Bates when she was about 19, remembers seeing pieces of fabric pinned up to an easel while Bates began airbrushing. “She started telling us how she wanted to start a punk rock skateboard club,” says Miller.

For the imagery, Bates took the heavy metal band Iron Maiden’s “Eddie the Head” mascot and modified it as the foundation—then each Hag added embellishments, including their nicknames. Bates’ had rhinestone eyes and hypodermic needles drawn on it. Another member’s patch had fluffy pink fur coming off of it. Others had musicians from the punk scene sign theirs. The patch for Gardia Fox (dubbed “Gardia the Good” once she became a Hag) still has a faded bloodstain from a tumble off her board. All the Hags attached their patches to denim vests. And while there were always plenty of friends and honorary crewmembers around, if you didn’t have a patch (known as “colors”), you weren’t an official member of the Hags. “If Sevie didn’t want you in, you didn’t get in,” recalls former Hag Mimi Claire, 52, now a radio DJ at Mana’o Radio 91.7 FM in Maui. “You had to be able to skateboard—maybe you weren’t good on a skateboard, but you had to be able to do it.”

Claire first met Bates in high school, and became one of the gang’s first members. “We’d skateboard around, go to shows, and be our own little posse of Hag girls. There was camaraderie with that. If one of us just skated around with a vest on, it was different than seeing a handful of us together. When you have a group like that, there’s a level of untouchability that comes with it. Your power seems to multiply.”

At the time, that power was intoxicating. While there are certainly all-lady skate crews in 2016—the Bronx-based Brujas and Meow Skateboards to name a few—in the ’80s, girls on boards were definitely an oddity. There were a few professional female skaters toward the end of the decade, and individual skater girls like Peggy Oki—the only female member of the original Z-Boys—occasionally gained notoriety. But when it came to making a splash en masse, especially out and about at punk shows, there was nothing else in L.A. like the all-female whirlwind of the Hags. They were radical.

Together, the Hags made a scene. They’d roll up to punk shows as a unit, sometimes on skateboards and sometimes on Bates’ motorcycle, wearing their colors. Their first public appearance as a gang was when they all skated to a Grandmaster Flash show at the since-shuttered Music Machine on Pico, Fox recalls. They sat in the front row showing their colors and holding their boards. “It was a pivotal time in my life,” says Fox, now in her 50s, from her home in Malibu. “It was a feminist statement. We wanted to encourage girls to skate, and show we weren’t just girlfriends of skaters.”

For Miller, the punk show-going side of their crew was its biggest attraction. The now-Ventura based journalist is currently working on a book about her life, including some memories from those heady Hags days, called Punk and In Love: A Memoir About Men, Music, and Hair in the ’80s. One of those memories centers around when Miller, Bates, and Claire were part of a well-documented riot during a show by the hardcore band the Exploited—known for its seminal record, Punks Not Dead. The venue was oversold and a mob of angry punks tried to break down the doors—the riot ended up on the local news as part of a series freaking out parents about the dangers of punk rock. The Hags trio ran away from the cops, crouching together in a gas station bathroom until the coast was clear.

A flyer for a punk show to benefit Raggy after she broke her ankle, circa 1984

A flyer for a punk show to benefit Raggy after she broke her ankle, circa 1984

Other Hags fondly remember rolling down Hollywood Boulevard, speeding over the iconic stars on the main strip. They’d go see their friends the Screamin’ Sirens, Alva’s band the Skoundrelz, Social Distortion, Circle Jerks, Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Cramps, or Tex & The Horseheads, or hit venues like Club Fuck! or Club Lingerie.

The Hags mostly skated for transportation, but Sacks also recalls skating for fun. “We would go at, like, two in the morning to parking structures in Santa Monica and luge skate down,” she recalls of their breakneck adventures speeding down parking ramps. She once shattered her ankle street skating during a visit to San Francisco with Bates and had to spend two months on crutches.

“Hags Headquarters was a safe place for the Hags and people who needed a safe place,” says Sefton. “We’re sisters, and we’re not going ?to let anything bad happen to our sisters.”

The gang even had its own clubhouse. Hags HQ was a ’50s-style, post-WWII, three-bedroom bungalow on the edge of Venice Beach, Mar Vista, and Culver City. It belonged to Hag Nancy Sefton’s helpful father, who had rented it to some of the girls. Hags lived there, others crashed from time to time, there were parties, and there was frequent roommate turnover. It was always packed with surfboards, skateboards, and a vintage pink beauty chair and shampoo station. And Sacks’ Pepto-Bismol pink Cadillac—which was often featured in pictures of the group—was almost always parked on the front lawn, especially after she lost the key.

Sefton had actually lived next door to Bates back in junior high, but didn’t start skating with her until years later when she met Fox. “I remember seeing [Bates] skating and was enamored with her and her skating, so when I met her, it was a thrill to have her interested in me as one of the Hags,” says Sefton, 54, who now lives between L.A. and Joshua Tree and manages bands. She was known as the “Mistress of the Manor,” which, of course, was on her colors. “Hags Headquarters was a safe place for the Hags and people who needed a safe place,” says Sefton. “[It was like,] you’re coming into a place that’s family, so respect it. We’re sisters, and we’re not going to let anything bad happen to our sisters.”

The Hags didn’t go unnoticed, and for a brief period in the summer of ’84, they had their unsolicited 15 minutes of fame, though you’d be hard-pressed to find anything about them online today. There were multiple articles about them in LA Weekly and the Los Angeles Times, and they were featured on a news program called 330. They were also briefly featured in the video for Pat Benatar’s “Ooh Ooh Song.” “We were a novelty,” says Miller.

“It was really cool,” says former Hag Sara Johnson, 52, who’s now working in avionics (aviation electronics) in Florida and volunteering at women’s prisons. “When Sevie started the Hags—well, we hung out with the Jaks, but we couldn’t be Jaks—so when she started it, it was a big thing. We were actually pretty famous that summer.”

An article about the Hags in the Weekly even inspired a 1986 cult movie called Thrashin’—sort of. Though the screenwriter admits the original idea came to him after he read about the Hags, he wrote his script about male skaters instead, and the few Hags who made it on screen were relegated to roles as extras. You can see Hags hanging out on a wall during an early skate scene, and Claire says she lost her board during the chaotic film shoot when she put it down for a minute and it vanished.

Hags colors (top to bottom): Sevie, Gardia, and Nancy

Thrashin’ also includes a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it visual reference to the Hags—some skateboarding actors roll up a wall spray-painted with the words “Flow Or Go Home.” This was the Hags’ motto, and was painted on a wooden sign above the door of Hags’ HQ. “It goes back to, like, surfing. You just have to be in the flow, get that ride, don’t go against the current. Be cool, be in the groove, get along or go,” says Claire of the motto’s origins.

“It meant be flowing, be cool, and come with gifts, you know?” Miller confirms.

“We had so many people coming over, the rule was, you bring something for us that we need,” clarifies Sefton. “Don’t come in and just drink our beer.”

“It just meant that you had to flow with us, with the vibe, with what was happening, or you had to get the hell out,” says Fox.

“Get with it or get the fuck out of here. No crybabies,” says Bates definitively. “It came from a punk rock kind of thing; it was a street movement.”

Sadly, despite their sudden spike in notoriety, the group fizzled just a year or so after forming. Some members fell harder into drugs and eventually found sobriety, others landed in prison before turning their lives around, and a few had disagreements that lead to broken friendships that have yet to be mended. Most of the Hags, however, have reconnected 30 years later thanks to the Internet.

Online, they share memories and upload flyers and fuzzy photos from their Hags days. “I’ve gone back to California and met up with Sevie and I go see Keren to get my hair done,” says Johnson. “It was definitely an amazing time, to be a part of that whole skateboarding era.”

Looking back, the former Hags all seem to feel that though their gang only lasted a year, the time they spent together had a huge impact on their lives. “We were part of a subculture in L.A. in the ’80s,” says Sefton. “It was something we were all very passionate about. Once we all got together, we created a little family during a time that was really challenging for all of us. To have these sisters, the Hags, was really important.”

Claire agrees. “We had this bond,” she says. “We knew we were taken care of and we would take care of each other.” She doesn’t skate too often anymore, but she has been teaching her 13-year-old son her favorite trick, the Bertlemann, where you crouch down and throw your hands on the ground while making a sweeping slide on the board.

“Even though we were these total party chicks, we were interested in social justice, though I hate that phrase,” says Miller. “We were rebellious and we wanted a different world and we wanted more acceptance. I remember the looks I would get.”

“I will say it was empowering, there was a strength in having this crew,” adds Miller. “Those rowdy, tough girls who didn’t take shit and paved their own way—those are core parts of who we are as people.”

Remembering the discrimination she faced that led to her starting the Hags, Bates says she’s happy now to see more opportunities for girls and women. “I remember wanting to take wood shop [in high school] and they basically told me I couldn’t do it,” she says. “I was just always fighting against all that prejudice. But now you have, like, girls’ snowboarding teams. That’s amazing to me. I wish I could have grown up in an era when women felt like they could do whatever they wanted to.”

But perhaps it’s no surprise that Bates succeeded in blazing her own path, despite the limitations placed on her. “People were always telling me, ‘You can’t do that,’” says Bates, with a clear spark in her eye. “Women weren’t supposed to be angry or have an attitude, and I had all those things.”

By Emily Savage

This article originally appeared in the December/January 2017 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

Photos Of Kabul’s Littlest Skaters Totally Shredding

TIME-SUCK ALERT: Adorable Skateboarding Birds

Three 6-Year-Old Girls Are Forming A Skateboarding Movement