Legendary feminist artist Carolee Schneemann has just been awarded Venice Biennale’s prestigious Golden Lion prize for lifetime achievement for her ‘direct, sexual, liberating and autobiographical’ work. Check out her interview with Miss Rosen in the latest copy of BUST below.

Artist. Feminist. Revolutionary. Carolee Schneemann, now 77 years old, has been traversing the sacred spaces of female sexuality and gender in the name of truth, liberation, and freedom from the patriarchy for more than half a century. Raised on a farm in rural Pennsylvania, Schneemann learned not to fear viscera, injury, or death. Instead, she embraced the creative and destructive forces of Mother Nature and fused them into work that challenged every assumption about women in the art world.

A multidisciplinary artist, Schneemann has created groundbreaking paintings, photographs, performance-art pieces, and installations that expose deep female secrets, pleasures, fears, and taboos. Using her body as a starting point, Schneemann also challenges cultural norms that discourage female artists from using their own nude bodies as the subjects of their work. Most memorably, in her landmark piece, Interior Scroll (1975), Schneemann stood on a table, assumed “action poses,” then slowly extracted and read from a scroll tucked neatly inside her vagina.

Her work shocked the establishment, but over the past 50 years, it has also become the foundation upon which generations of artists and pop-culture figures stand. From Matthew Barney to Lady Gaga, Schneemann’s influence is vast, yet she remains a solitary figure in the world of art, constantly reinventing her methodologies to examine the beauty and horrors of life in equal measure. On the cusp of her first United States retrospective, “Kinetic Painting,” at MoMA PS1 (running from October 22, 2017 to February 1, 2018), Schneemann spoke with BUST about her iconoclastic life in art.

Still from performance of “Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera” (1963), photo: Erró

Still from performance of “Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera” (1963), photo: Erró

When did you realize that art was your destiny?

I started obsessively drawing, the way many children do, when I was four, but I made very complex, remarkable drawings. Some of them were in sequences with a narrative [up to 15 pages long]. It was filmic. In a way, they were predictive of everything that was going to happen later. By the time I was seven or eight, I still didn’t know what an artist was. My family didn’t want me to concentrate on anything except being a normal girl. I got a full scholarship to Bard, and once I was there, my best teacher said, “Well kid, don’t set your heart on art, you’re only a girl.”

Above: “Red Figure” (1961) Oil on Masonite.

Above: “Red Figure” (1961) Oil on Masonite.

How did the presumptions of female inferiority influence you?

It’s always mixed messages. My father was a rural physician. He let me look in his anatomy books, things that other kids were not allowed to experience, especially girls. I traveled around with him to get out of the house and away from female work. I was watching this other side of it. It’s different in the country. Once you’re in the tradition of the farm wife, there’s another kind of oppression. Everything belongs to the men: it is part of their control and inheritance. Even when the country life is full of collaboration, there is a premise of husbandry. That’s where feminism has to start with all of this: the assertion of equity.

“Dark Pond” (2001), hand-colored digital print, watercolor and crayon on paper.

“Dark Pond” (2001), hand-colored digital print, watercolor and crayon on paper.

How do you define female and feminine?

You know, I never quite did that [laughs]. It’s especially complex because everyone who is compelled to change their gender is able to try, so that makes a specific, formalized definition difficult. On the other hand, you recognize the suppression of what is female or feminine when you have governmental structures that will deny you control of your own body. I’ve been very concerned about the denial of pleasure, the denial of orgasmic experience. Many experiences of female power and pleasure create great envy in the male psyche, or great terror: the terror of being born with a vagina.

“Testing Energy” (1970) Collage on paper

“Testing Energy” (1970) Collage on paper

Why were your nude self-portraits so controversial to both the male establishment and feminists alike?

They didn’t sustain male expectations. I wasn’t sure how it would resolve, but I had to keep this experiment happening. It was always the poets who really got the direction of what I wanted to bring forward. Whereas in the early days, many feminists found the work prurient. My work with the body was taken as playing into male fantasies. That was very disappointing for me.

“Interior Scroll” (August 1975). Photo: Anthony McCall

“Interior Scroll” (August 1975). Photo: Anthony McCall

A man attacked you during a performance of your work, “Meat Joy,” in Paris. [In the performance-art piece, eight partially nude performers dance and play with various substances, including wet paint, sausage, raw fish, scraps of paper, and raw chicken.] What happened?

He dragged me off to a corner and was strangling me and I couldn’t even scream. I understood, instantly, that this was the kind of reaction that dammed up, frustrated, distorted men could have—that all the exuberance and sensuality could make them crazed and violent. I was saved by two middle-aged women in fur coats. Everyone else thought it was part of the performance, and these two bourgeois ladies registered, “This is wrong. She is getting hurt.” They ran over and started hitting him and dragged him off. I went back into my work in the group and never got to thank the women or see them again.

“Meat Joy Collage” from performance of “Meat Joy” (1964), mixed media collage on paper.

“Meat Joy Collage” from performance of “Meat Joy” (1964), mixed media collage on paper.

You tap into such intense places. Where does that come from?

I basically say, “This is so awful, so appalling. Why doesn’t everybody speak about it? Look at it? I better make something.” Then that work becomes controversial or brave, but to me, it’s not brave. I think, There’s a corpse in the road—somebody better move it. Well, I better move it.

Still from performance of “Meat Joy” (November 1964), photo: Al Giese.

Still from performance of “Meat Joy” (November 1964), photo: Al Giese.

What is it that allows you to break with expectations and be completely free as an artist?

My video “Devour” is very purposefully a double projection. One side is all harmonious, simple, pleasant domestic images and the adjacent side is all terror, murders, and explosions. My curiosity always seems to move between the harmonious and the horrific, and that’s what our lives are about.

Still from performance of “Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera” (1963), photo: Erró

Still from performance of “Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera” (1963), photo: Erró

Meat Joy 1964

Meat Joy 1964

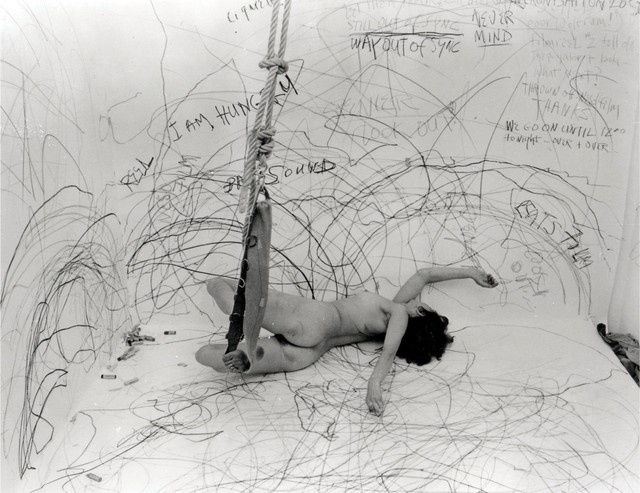

Top photo: Still from performance of “Up to and Including Her Limits” (June 1976). Photo: Henrick Gaard

By Miss Rosen

All images courtesy of the artist

More from BUST

How One Fashion Journalist Is Making It In Media — While Following Her Orthodox Jewish Faith

This College Student Invented An App To Help You Find Books By People Of Color

Sweet Lorraine Founded NYC’s Only All-Black Burlesque Revue: BUST Interview