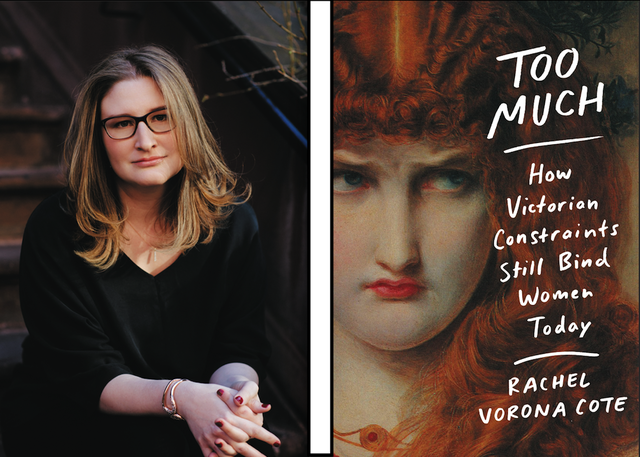

When I read Too Much: How Victorian Constraints Still Bind Women Today, I knew I had to interview Rachel Vorona Cote. Cote outlines the book with personal anecdotes from throughout her life and analyzes constraints she’s faced and beauty standards she’s noticed alongside stories from both the Victorian era and popular culture today. Ultimately, she encourages women to reconsider what is, in fact, beautiful.

This interview has been condensed for clarity.

What prompted you to write this book?

I’m personally invested in the conversations surrounding women’s excess, the way that women are stigmatized and regarded with being excessive, whether talking about our emotions, our bodies, our desires, the sound of our voice. I think that this is a really urgent conversation, and I wanted to come at it from something of a literary historical angle to [analyze] a little bit of the history of hysteria and about the subjugation of women. So specifically the Victorian history – I think is crucial to this conversation.

Together with that I wanted to think about this specific term “too much,” and that brings me to the other way that I would address this question, and that’s with a little anecdote that I talked about in the book.

I saw Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland adaptation in 2010, and there was a term that was used in the film that was stuck in my head – “muchness.” Alice is, I think, 18 – and she’s not really thrilled with the way that her life is going and she’s expected to marry this milquetoast dude, and instead ends up back in Wonderland. There everybody is concerned that Alice has lost her muchness, and what that means, is that she’s lost in her verve, her spirit, her chutzpah – and so you know she’s not the spunky little girl she once was. The question becomes, how does she regain this muchness, how does she summon it? Was it gone or was it there all along? In any case, she summons it by the end and she becomes a hero.

I was so fascinated by this and if you had just said to me – here’s this word muchness, you know it’s not a real word, give it a definition, I would’ve come up with something really negative, kind of self-castigating. I think that’s because I’ve always had this sense that I was too much, that muchness – it suggested something excessive. In this film, I think that you could make the argument that it means something excessive, and it’s positive. It had never occurred to me that it could potentially be regarded that way, so the fact that the term was used in such a positive way, it piqued my interest, and it caused me to start asking questions about the way we talk about excess, and the very gendered way in which we talk about it.

Do you hope that this book contributes to the conversation on women’s rights, and what we can do for progress in terms of language and how to view this excess?

I think that we live in language. We are language-based creatures and we’re always looking for meaning. I don’t think we’re ever really fully going to be able to detach ourselves from the potential meanings to being this or that. What I’d like is for more attention for language, and for us to engage it with more empathy and compassion, to think about it in a more nuanced way.

I think ultimately that people navigate the world with empathy and compassion, and so I think absolutely that there are aspects of femininity that have been stigmatized as excessive, and therefore because of the way that patriarchy has imbued that term, that [femininity] is excessive and further bad. So yes, I think that there is a lot of promise and beauty and potential there [in terms of progress].

In the book, you reference the song “Too Much” by the Dave Matthews Band, and this is part of your book’s title. Did you come up with this title before writing, or while writing, were you listening to the song — how did that happen?

I remembered the song after I started working on research for the book. When I went in college in Virginia, people were using AIM profiles, and the Dave Matthews Band, if I’m remembering correctly, started playing in Charlottesville, Virginia. So if you went to school in Virginia, you knew the Dave Matthews Band, and this song — “Too Much” — was just on everybody’s AIM profile and on their away messages – I think maybe to indicate that they were at a party, probably because of the lyrics. I hadn’t thought about it at the time. But years later, working on this book, I was thinking it’s sort of interesting the way that the song is triumphant; when Dave is saying, “I drink too much, I want too much, too much,” he’s not really ashamed of it because he’s sort of reveling in his excesses, and that’s okay. I think that because there’s a lot more room for a white cisgendered man to be ravenous, to get really drunk, and to be really horny. I think that if anybody else had put out that song, not Dave Matthews – it might’ve been received differently. I don’t know if it would’ve been as popular as if it had been sung by a woman.

There’s a lot of references to English literature from the Victorian era in the book. Might you have a favorite, and why?

I love the novel The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot. I love [the protagonist] Maggie Tolliver because I empathize with her so profoundly. I love the way that Eliot pays attention to people’s minute particulars – and she’s also very funny. I love the way that she writes Maggie first as a young child and then as a woman. Maggie tries so much to live and she’s deeply imperfect, she can be at times difficult, a little full of herself, but she wants so much to be good. And so the way that you watch her resist all of the social forces that are so determined that have been basically mechanized to suffocate a woman, it’s agonizing, but it’s so explicitly done. I would say that it’s a novel that is still relevant today, there’s a whole conversation about slut shaming, where it’s not specifically called that, but there’s a sex scandal that Maggie becomes entangled in, and the result in discourse – well it’s shitty that it feels so reminiscent of things that we hear today, but it does.

What’s your advice for aspiring writers?

Read, read everything, read voraciously, read in the genre that feels connected to the sort of work you want to do, but read outside of it too.

Top photo by Sylvie Rosokoff