A 30-something asexual woman reveals the truth about her oft-misunderstood orientation

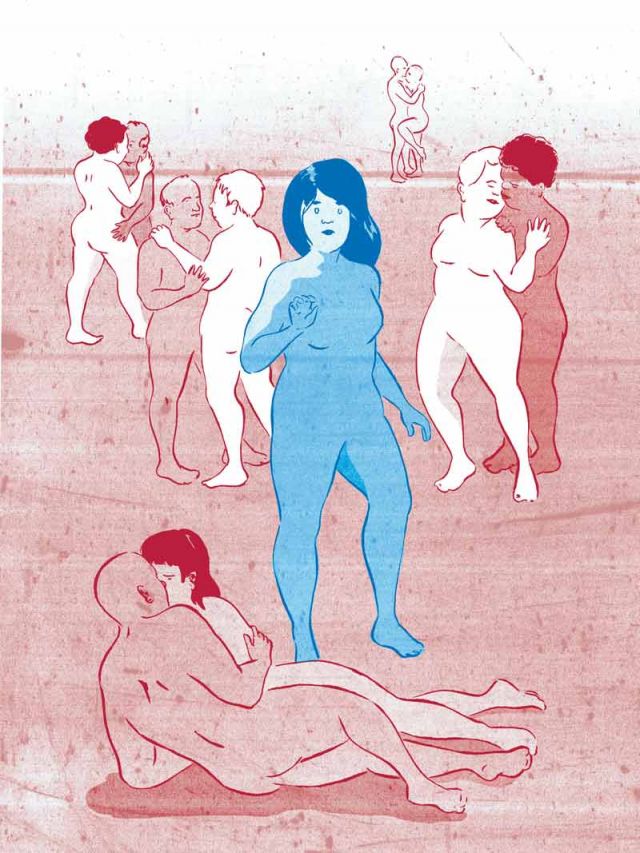

By Keira Tobias // Illustration by Emily Flake

I remember it clearly: I was in the sixth grade, and my mom asked me which boy I had a crush on. I refused to give a name, but she pressed on, asking which actors I thought were cute. I felt acutely embarrassed by the question, and didn’t want to answer her, but I finally said Ethan Hawke (this was the era of Reality Bites) just to appease her, and then changed the subject. I had that same feeling years later, eating lunch with the girls at work and staying silent during their conversations about birth control. They assumed I was on the Pill, too, because they assumed I was having sex with guys. I wasn’t.

I thought maybe I’d have an epiphany one day and realize I was a lesbian. My best friends in high school were gay, and I knew I’d be accepted by them if I was, also. But the revelation never came; I never had the slightest bit of more-than-platonic interest in girls, either. Then, when I was 20 years old, I found myself in a relationship with a man.

It was complicated, I guess, but it didn’t feel that way. He was my best friend. I didn’t call him my boyfriend, because to me, “boyfriend” was a very heterosexual word, and I always knew on some level that I wasn’t heterosexual, and neither was our relationship. Like almost any other couple, we hung out all the time, obsessed over shared interests, held hands, cuddled, and shared a bed. We just happened to never have sex in that bed. The fact that we didn’t have sex was a non-issue, something we didn’t address explicitly. I didn’t think of it as unusual.

We broke up after five years together, and it was then that I was forced to acknowledge how uncommon my relationship experience was. The first time I tried dating someone else, I was overwhelmed by his sexual attraction toward me. I really liked him and thought he was cute, but the night he said, “I want you,” I freaked out. I didn’t want him in the same way; I didn’t want to take things to the next level. I stayed up all night while he slept beside me; the next morning, I told him I had never had sex, not even with my ex. He broke up with me shortly thereafter.

I had never wanted to have sex with anyone, and I knew that would never change.

I agonized about it all summer, wondering what was wrong with me. Around the same time, I made a friend who was completely uninterested in sex and dating, and she told me she was asexual. I went home, Googled the word, and found AVEN, the Asexuality Visbility and Education Network (asexuality.org). There was one sentence, set in a purple banner across the top of that website, that changed everything: an asexual is a person who does not experience sexual attraction. Here was the epiphany I had longed for, words that summed up the feeling I had been unable to express for my whole life. In 25 years, I had never wanted to have sex with anyone, of any gender, and I knew that would never change. I wasn’t a freak—I was asexual. And I wasn’t alone. An estimated one percent of people are asexual, which may seem like a small amount, but to me, that number felt huge.

I read on and learned a lot of things that night, about myself and about the asexual community. I learned that asexuality is a sexual orientation, different from celibacy (the choice to abstain from sex). I learned that it’s possible to have a sex drive and to experience feelings of arousal, but for those things to exist independently of the desire to actually have sex with anyone. The same goes for romance and sex; the former can be experienced without the latter. This is a difficult thing for a lot of people who aren’t asexual to understand. But then again, I think most people in general would find it hard to explain why, exactly, they make out or have sex or even just like someone. And most aren’t asked to—it’s only those of us who experience things differently who are expected to explain ourselves. For me, I just know that physical intimacy and sexual intimacy are completely separate things. I want one and not the other. I find it very comforting to be physically close to a partner, which can include holding hands, hugging, cuddling, and kissing. These actions are an expression or an extension of emotional intimacy, and they feel good. They just don’t have any connection to a desire to see someone naked or have sex with them. A person’s libido is driven by hormones, and arousal is a natural response to stimuli—but neither of these things are the same as attraction. My body can feel aroused when kissing someone I have feelings for, but my brain draws the line at actually wanting to have sex with them.

And yes, some asexual people masturbate. According to the Asexuality Archive’s Guide to Masturbation (asexualityarchive.com), masturbation is a physical act that does not require sexual attraction. “Whether or not you masturbate has absolutely nothing to do with whether or not you’re asexual,” the site states. “Many asexuals who masturbate say they do it because it feels good. There is nothing un-asexual about masturbating strictly for pleasure.” There are plenty of people who get off without fantasizing about sex, who do it to relieve stress or fall asleep. There are also plenty of people who don’t masturbate at all, just like there are plenty of people who don’t collect records or do yoga.

Sound confusing? It can be, but the most important thing I realized that night was that there wasn’t anything wrong with me. It was a massive relief to finally be able to attach a word to my complex set of experiences, and to know that there were other people like me—“aces,” as we often call ourselves. I like the nickname.

One of the people I connected with through the AVEN community was Emily, 30, who identifies as a bi-romantic asexual (meaning she is romantically—but not sexually—attracted to men and women). “I want all the typical things from a romantic relationship…emotional intimacy, commitment, even touch, but I don’t have the need for sex that most people do,” Emily says. “Even though most asexuals separate sexual and romantic attraction, I don’t think there’s any consensus on what romantic attraction is. We just agree that it’s something different from ‘you are a cool friend’ and ‘I want to have sex with you.’”

I want all the typical things from a romantic relationship…emotional intimacy, commitment, even touch, but I don’t have the need for sex that most people do.

Some of the asexual people I know are aromantic; they lack interest in any romantic relationships, and have never kissed or dated anyone. Others identify as “grey-A” and experience sexual attraction to a limited degree, or, in the case of “demisexuals,” only within emotionally intimate romantic relationships. There are asexuals who find themselves attracted to television characters as they get to know them over the course of a season, but feel no stirring in their loins for the actors who play those characters. There are asexuals who love to cuddle and be held, but have no desire for intimacy past that. I had once assumed that a married couple I knew was heterosexual, but I later found out that they were actually both asexual, and had never had sex. In fact, they were media representatives for AVEN, and had appeared on television to talk about how (or rather, why) they didn’t have sex on their wedding night. You’d almost certainly never be able to tell that a person was asexual unless they told you themselves. Still, Emily says, “Some asexuals pass as heterosexual, but some are gender-nonconforming, and some have faced homophobic or transphobic discrimination.”

With such tremendous diversity of identity and experience within the asexual community, some of us may have almost nothing in common with each other besides the fact that we don’t experience sexual attraction. And yet, in a society that is obsessed with sex and assumes that every human is driven by nature to seek it out, I’ve found it’s a great comfort to be around other people who share my experience of the world and relationships. When I found the asexual community, it was largely based around AVEN’s message boards and a small number of blogs. Today, there’s a much wider network of resources, including multiple books and a lot of activity on Tumblr. Asexuality has been called the first “Internet orientation” because so many people discover asexuality and connect with the community online, but there’s also a strong network of meet-up groups in different cities.

I’ve come out as asexual to my oldest and closest friends, but not to my family or most of my current friends. I generally find myself not knowing how to bring it up, and feel like I’d be sharing something overly personal, even though it’s just my orientation. I don’t like to draw attention to my lack of sexual interest or invite probing questions. I’ve also been on the receiving end of ignorant comments from even my most liberal queer feminist friends, like, “Maybe you just haven’t met the right person yet.” Sometimes I struggle with the feeling of being responsible for educating people—I don’t want to speak for every asexual person’s experiences—but it’s important to me that we are seen and heard.

Emily, who marches in her city’s LGBT pride parade every year with a contingent of people from AVEN, explains why visibility is crucial for the asexual community. “Asexuals often feel broken and alone,” she says. “If we don’t understand ourselves, we’re at risk for unwanted sexual activity, coercion, and self-hate. Before I learned about asexuality, I just thought I was a failed heterosexual, and I had no language to describe my experience to myself or others.”

Before I learned about asexuality, I just thought I was a failed heterosexual, and I had no language to describe my experience to myself or others.

I have now been single for seven years, and I don’t feel like my life has been lacking because of it. I think it would be nice to have a partner again someday, if a compatible person came along. I used to be hesitant to tell people I was asexual, due to a deep fear of being immediately dismissed as “out of the running” to be their partner. My ego couldn’t stand that idea. It took years (and therapy) to build self-esteem and understand that my worth doesn’t lie in my compatibility with a person. Unlike a lot of my friends, I feel little motivation to date or spend time specifically trying to seek out a relationship. And now I know that’s just fine—it doesn’t mean that I’m going to be alone forever, or that I’m alone now. I find that my need for emotional intimacy is met quite well by my close friendships.

“I’d like people to understand that asexuals are extremely diverse, and while asexuality might shape our lives in certain ways, it’s still just one part of who we are,” Emily says. “You sometimes hear that asexuals can fall in love and get married just like everyone else, but I’d prefer to say that we aren’t like everyone else, and that’s perfectly OK.”

Although I am personally ambivalent about having sex, I do consider myself a sex-positive feminist. The great thing about the term “sex positive,” from what I understand, is that it encompasses acceptance of the full spectrum of sexual identities, preferences, and (safe, consensual) behaviors—including not being interested in having sex. I believe that no one should be made to feel ashamed of their sexual desires or activities, or lack thereof. A common thing asexuals hear is, “You’re missing out.” But I don’t think it’s really possible to miss out on something you have no interest in or don’t enjoy, whether it’s country music, baseball, cilantro, or sex. I have plenty of other interests. My life is busy, and it’s great. There’s an inside joke in the asexual community about how we’d rather have cake than sex. So don’t tell me what I’m missing—just pass me a slice.

This article was originally published in the print edition of BUST Magazine, June/July 2015. You like it? You should subscribe here and get this awesomeness mailed to your door, on paper, it looks pretty damn good that way.