Every few months I say I’m going to write it. My big OCD opus. I say it’s going to be an article or a film or a novel—a few times I’ve started writing a screenplay or a short story exploring the mad world of irrationality. Only I never finish the articles or the novels or the screenplays. Because sometimes saying those three letters out loud is a battle all by itself. And somewhere along the way the shame crept in and stole my courage. I don’t talk about my OCD anymore. After all, my stomach flips just typing out those rounded little letters.

As a kid, it was never like this. I was diagnosed with obsessive compulsive order in grade school and I displayed odd behavior, yes, but I was always willing to talk about it. “Hey Emily, why are you blowing on your arm?” “Hey Emily, why are you doing that?” “Oh, it’s my OCD. OCD is a chemical imbalance in the brain, let me tell you all about it…” And my mom was a therapist, so not only was I comfortable discussing my problems but I felt like something of an authority on them. At least on the playground. I had yet to see others exhibit my behaviors, and so my only point of reference was personal experience.

For those of you not in the know, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder is an anxiety disorder often associated with “germophobic” or “perfectionist” behaviors. While OCD can lead to perfectionism or a fear of germs, it isn’t just about neat freaks and highly efficient organizers. Shocking, I know. So, what is OCD exactly? In simplest terms, it is when you engage in routine or “ritual” behavior because you are convinced something bad will happen if you don’t. Fear and panic surge in your body, setting off alarms in your brain. Like a smoke detector beeping even though there isn’t any smoke.

I’m not sure which came first—if I stopped talking about the compulsions because they got out of hand, or if the compulsions got out of hand to the point where so much as saying the words “obsessive compulsive” went against my rigidly devised code of irrational behavior. That’s the funny thing about OCD though: you are very aware of what is you’re doing…and you are very aware that your brain is sending out false signals of fear and dread. Only knowing that you’re being irrational doesn’t make you less irrational. It just makes you loathe yourself for it.

It doesn’t help that OCD is like the weird little sister of mental health problems. It’s overlooked and misidentified, developing something of a false reputation…so when people do finally notice it, they see it for what they expect to see and not for what it is.

My friends accepted my OCD growing up as a facet of my existence—the same as if I’d worn glasses (I didn’t) or was bad at sports (I was). Of course, sometimes my classmates still made fun of me, but I understood that they did so out of immaturity and ignorance. Only later did I start to see the pattern society was following—the caricature it had turned OCD into.

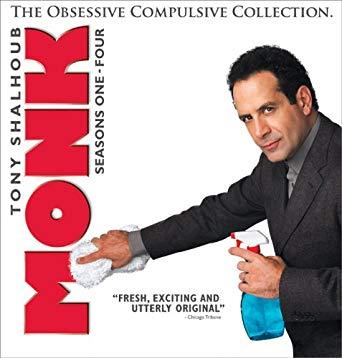

Monk’s “Obsessive Compulsive Collection”

Monk’s “Obsessive Compulsive Collection”

The first time I really noticed it was with Monk, which got great reviews. To this day, it holds eight out of ten stars on IMBD. The series, which ran from 2002-2009, was marketed as a comedy about an obsessive-compulsive detective. I could never bring myself to watch it, but I read about it enough to know that it grated at me. Regardless of the show’s content, the network marketed the program using OCD as a gimmick and a punchline. It annoyed me, but I never said anything about it. Because it got good reviews. And because people seemed to like it.

Then, a few years later, I caught an NCIS rerun that startled me. A character by the name of Nikki Jardine was introduced as having an aversion to germs. The way other characters looked at her made the word “quirky” immediately jump into my brain. Because characters with OCD go one of two ways on television: they’re either there to be laughed at, or smart enough for their behavior to be deemed acceptably “quirky” and, therefore, tentatively tolerable. Only, “quirky” suggests a levity that does not exist within the realm of compulsive behavior. If you are trying to close a door for the eighth time or switch a light off for the thirtieth, it is not because you enjoy doing it. This is, perhaps, the greatest misconception when it comes to OCD. This is the reason I always hated when, in high school, people said, “I’m just OCD about this” to describe their own pickiness. People think those with OCD feel gratification through their rituals, when really, we’re just trying to avoid feelings of misery and despair. I don’t do what I do because I like it. I do it because I’m afraid of what will happen if I don’t.

Lots of shows have normalized the way people laugh at OCD. Friends, which has always been one of my favorite comedies, used the condition for a throwaway laugh during season four, episode eleven (“The One With Phoebe’s Uterus”), when one of Ross’s coworkers introduces himself by saying, “I have to turn a light switch on and off 17 times before I leave the room or else my family will die.” Additionally, Monic Geller, while never officially diagnosed on the series, exhibits a lot of this behavior for laughs. Cleaning. Organizing. Keeping everything just the way she “likes” it. The Big Bang Theory, another program I enjoy, walks this line a lot with Sheldon Cooper.

Monica on “Friends”

Monica on “Friends”

Movies also have a tendency to confine OCD portrayals to comedic spaces, as in the 1997 romantic comedy As Good As It Gets. Matchstick Men and Dirty Filthy Love, both following obsessive compulsive protagonists, opt to take more of dramedy route. They take the disorder somewhat seriously, sure, but they are still looking for the humor in it. I understand that sometimes you need to laugh in the face of pain, but when people are only laughing at that pain…then you have a problem.

The first time I ever saw my condition (and I really hate the word “condition”) represented with any brutal honesty was when I saw Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator in 2004. And the real kicker, there? It wasn’t even marketed as—and isn’t remembered for being—about OCD. People know it as the Howard Hughes movie. And who was Howard Hughes? An eccentric millionaire. When you are poor or middle class, your OCD is coded as “quirky,” but when you’re rich you get bumped to being called “eccentric.”

There is a scene in The Aviator in which Hughes washes his hands so hard and for so long that they start to bleed. It may seem like a great obsessive-compulsive cliché, but the look on his face—the determination to complete this task blended with a genuine resentment for it…that is the OCD I grew up with. That is the OCD people around the world live with. It is the one and only time I ever saw my struggle in a show or a movie that was in no way, shape, or form a comedy. This was a serious drama by an acclaimed director with a A-list cast. For these people to take this disorder and portray it for what it is astounded to me. Because no one had ever done that. The Aviator isn’t about a punchline and, perhaps more impressively, it doesn’t seek to cure its subject by the end of the film. Hughes is still struggling by the end, because OCD never really goes away. It can be managed and the impact of it can be contained, but it doesn’t vanish. Success or fame or love never come along and obliterate it like magic. You just endure. You fight the battles, big and small, every day.

There are two facts about OCD in television and film that I find to be most striking. First of all, The Aviator was released in 2004. That means it has been fourteen years since OCD was correctly portrayed onscreen. Second of all, I recently realized that none of the movies about OCD focus on women. Not a single one.

As a society, we say that the stigma around mental health concerns needs to be removed, but as an obsessive-compulsive woman, I’ve always felt out of that loop. I don’t even call it OCD anymore, I refer to it as anxiety. I have an anxiety disorder. This umbrella term just seems easier for people to digest.

But you know what? I’m tired of waiting around for someone to get up on a soapbox and explain it to the masses. So here I am. Regretting every word as I write it. Prying each statement like meat from bone. Telling myself even as I put the words on the page that I should never publish this. I want to make a name for myself as a writer, not the writer with OCD. Only someone needs to start this conversation. It’s fourteen years overdue.

I’m not saying OCD is a tragedy (though sometimes it certainly feels like one), but it sure as hell isn’t a comedy either. It’s fact of life—my life, and for the lives of over three million people in this country. So, let’s get it right, shall we? Let’s tell people what it is before we make fifty more dramadies and comedies about it. I am willing to laugh at my problems, but only after everyone else stops laughing at them with such ignorance. OCD is real. And it’s embarrassing. And it hurts like hell. It’s a disorder that effects real people, and media should reflect that.

top photo: Friends

Published August 16, 2018

More from BUST

How Prozac Helped Me Step Back From The OCD Ledge

Amen, Amen, Amen: Memoir Of A Girl Who Couldn’t Stop Praying (Among Other Things)