A crazed woman in her underpants, 100 feet tall, rages through city streets, leaving behind a trail of menstrual blood and destruction. Empty bottles and scattered household items threaten revolution and murder. There are lots of bad dreams: Vomiting up teeth, penises that turn into croissants.

This is the visceral, over-the-top world of Dirty Plotte, splattered with the figurative guts of comics artist Julie Doucet. The cult series was first published in the early 1990s, ferried around the underground world through word of mouth, the mail, and your local alternative comic shop (if you were lucky). These were the heady days when punk was breaking into the mainstream, riot grrrl was rumbling through the United States, and artists like Dan Clowes and Chester Brown were carving out a place for comics that went beyond superheroes.

Today, Doucet is part of feminist canon in the comics world and beyond—she’s even name-checked along with Judith Butler and Angela Davis in Le Tigre’s call-to-arms anthem “Hot Topic.” And Dirty Plotte is getting a beautiful re-release this month in a two-volume set from Drawn & Quarterly, encompassing the taboo-breaking comic, several essays placing it in context, and some of Doucet’s additional work and ephemera.

Some of the images in Dirty Plotte might seem shocking. At its core, the comic is about a sort of shadow fantasy world that picks of elements of Doucet’s own life, then blows them up—sometimes literally—into grotesque, always hilarious proportions. It is a comic about a woman being uninhibited, messy, gross, inconvenient to men, and sometimes inconvenient to herself.

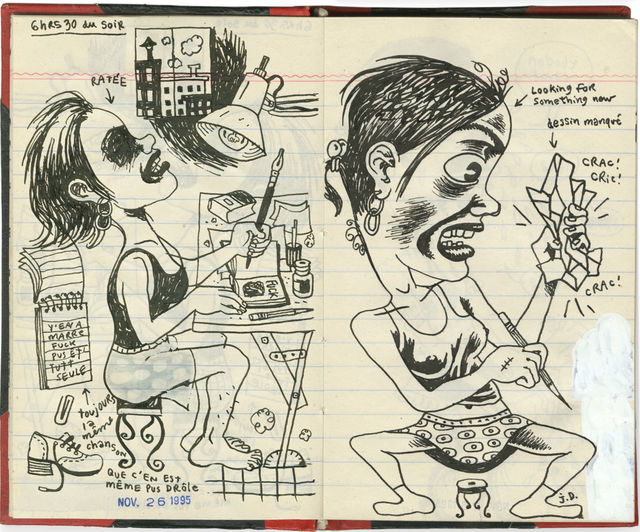

Part of that unvarnished quality comes from the fact that Doucet initially had no intention of publishing the comics. “I’m very compulsive,” she says. “It’s not like I was thinking that far ahead. It was just something where I felt like, ‘I have to draw this.’ I had no idea it was going to be published, I wasn’t thinking of anything being public. It was just for myself, a way to get out the bad feelings. Just demolish everything with drawing.”

In the early days of Dirty Plotte—which translates to “Dirty Cunt” in French—some places refused to even carry the comic. “There was this bookstore in Montreal, a feminist bookstore that was distributing the comic. They didn’t want to sell it because there was too much violence against women,” Doucet recalls. But that violence is always turned on its head in Dirty Plotte: A sleazy reader named Steve sends in an unsolicited nude photo, declaring, “My body belongs to you.” Doucet takes this literally, devoting an entire gleeful strip to mutilating poor Steve’s corpse after hitting him in the head with an ax. “They just didn’t get it,” she says.

At the time, Doucet didn’t see her own work as inherently feminist. “I didn’t have any intention that way,” she says. “I wanted to be part of that, but I didn’t feel like I belonged. The way other feminists were talking, I wasn’t part of that movement. I really didn’t feel that comfortable with women in general. I related better with men. So, I was surprised to hear it called ‘feminist’ work, which is obvious, looking at it now.”

In the mid-’90s, most of the major players in the alt-comics scene were men: Clowes and Brown in particular had clout, and as contemporaries of Doucet, promoted her work to their own audiences. “I felt very comfortable with that for a long time, but eventually not at all,” she says. “That’s one of the reasons I quit comics. I couldn’t relate to anyone around me. There weren’t many women drawing comics at that time.”

“It’s completely different now,” she says. “I think if I started drawing comics today, I wouldn’t quit. Because it’s so much more open, and so many more women are doing great stuff.” (As an example, Doucet points to the work of Quebec-based artist Diane Obomsawin, author of On Loving Women, a story of lesbian romance told by anthropomorphic animals.)

The Drawn & Quarterly re-release also features some of Doucet’s post-Dirty Plotte work, including 365 Days, a visual diary of her time as a New Yorker. That project marked a return to her comics work following a long fallow period. “I had a burnout, I was totally unable to draw,” she remembers. “To be creative was something I didn’t have anymore—it was useless to try to draw.”

These days, Doucet is focusing on fine art, especially sculpture. She doesn’t consider herself solely a comic artist. But the re-release of Dirty Plotte has her realizing her impact on the genre. “It’s hard for me to tell, because the comic is so close to myself,” she says. “But I think it goes through time very well. I have young women coming to me to say they love my comics, so it’s not just a time capsule from those old days.”

images via Drawn & Quarterly

More from BUST

Interview: A Minute With Comics Artist Megan Kelso

5 Women Graphic Novelists You Should Be Reading

“Eternity Girl” Is An Imaginative, Darkly Funny Comic About Depression