According to historians, the legend of the unicorn first emerged in 398 BC, courtesy of the Greek physician Ctesias. Ctesias wrote an account of India, titled Indica. In it, he attests that all recorded within his account are things that he has witnessed himself or that he has had related to him by credible witnesses. This account of India, though largely lost, has been preserved in a fragmentary abstract made in the 9th century by Photios I of Constantinople. In the twenty-fifth fragment, Ctesias writes of the unicorn, stating:

There are in India certain wild asses which are as large as horses, and larger. Their bodies are white, their heads dark red, and their eyes dark blue. They have a horn on the forehead which is about a foot and a half in length.

Ctesias describes the unicorn’s horn as being “two hands’-breadth above the brow” with a base of pure white, a black middle, and a “vivid crimson” tip. He goes on to write of the uses of unicorn horn, claiming that the dust filed from the horn, when administered as a potion, is a protection against deadly drugs. He also states that those who drink from the horn are not subject to either convulsions or epilepsy, writing:

Indeed, they are immune even to poisons if, either before or after swallowing such, they drink wine, water, or anything else from these beakers.

Portrait of a Young Lady with a Unicorn by Raphael Santi, 1505.

Portrait of a Young Lady with a Unicorn by Raphael Santi, 1505.

His descriptions of the unicorn’s anatomy and physiology are specific. He states that the unicorn has an ankle-bone “like that of an ox in general appearance and in size.” He also states that, unlike “other asses,” the unicorn has a gall in its liver. He also declares that “The animal is exceedingly swift and powerful so that no creature neither the horse nor any other, can overtake it.”

This is all a very different description than the solid white, golden-horned unicorn of modern fantasy and might go a long way toward explaining some of the stranger depictions of unicorns in early art, wherein they resemble a goat, a sheep, or a strange variety of small, brown horse. Author Odell Shepard, in his book Lore of the Unicorn, posits that Ctesias is describing the combined attributes of more than one animal in his description, primarily the Indian rhinoceros. As he explains:

The evidence for this lies in what is said of the horn’s alexipharmic virtue, that those who drink from beakers made of it are free from certain diseases and from poisons. This belief about rhinoceros horn, still widely current in the Orient, was already old, apparently, in the time of Ctesias, and underneath it there lies a welter of symbolism and superstition exceedingly difficult to comprehend.

Saint Justina with the Unicorn by Moretto da Brescia, 1530.

Saint Justina with the Unicorn by Moretto da Brescia, 1530.

The fragmentary passage by Ctesias is considered to be one of the two primary sources for the western legend of the unicorn. In the years that followed, though single-horned “wild asses” were acknowledged by the likes of Aristotle, the unicorn had no place in the classic literature of Greece or Rome. Nevertheless, according to Shepard, the legend of the unicorn continued to grow. Not only were unicorns mentioned by Julius Caesar and Pliny the Younger, but also by Roman author and teacher Claudius Aelianus (also known as Aelian). In his book, De Natura Animalium, Aelian writes three passage about the unicorn and, according to Shepard:

Every phrase of his three considerable passages about the unicorn was conned and reiterated many times during the following fifteen hundred years and for this reason they deserve careful attention.

The Lady and the Unicorn by Luca Longhi, 16th Century.

The Lady and the Unicorn by Luca Longhi, 16th Century.

The first and second passages by Aelian seem to mirror the writings of Ctesias. In the third passage, however, Aelian’s description begins to diverge from his predecessor, stating:

…there are mountains in the interior regions of India which are inaccessible to men and therefore full of wild beasts. Among these is the unicorn, which they call the ‘cartazon.’ This animal is as large as a full-grown horse, and it has a mane, tawny hair, feet like those of the elephant, and the tail of a goat. It is exceedingly swift of foot. Between its brows there stands a single black horn, not smooth but with certain natural rings, and tapering to a very sharp point.

Aelian mentions other qualities of the unicorn which bear striking resemblance to the rhinoceros, including its “dissonant voice,” indomitability, propensity for solitude, and tendency to fight with other males and even with females. Shepard notes that, rather ironically, though at the time the rhinoceros was known to both Greeks and Romans, Aelian does not seem to make the connection. He writes:

The strange confusion had strange results, lasting on into the nineteenth century. One of the more amusing phases of it is the fact that when Aelian is speaking of the wild ass he makes much of the magical properties of its horn, but when he comes to speak of the “cartazon,” or rhinoceros, to which alone those properties were originally attributed, he has not a word to say of them.

The Mystic Hunt of the Unicorn by Martin Schongauer, 1489.

The Mystic Hunt of the Unicorn by Martin Schongauer, 1489.

The unicorn has often been intrinsically linked to Christianity. Not only are unicorns mentioned several times in the King James Version of The Bible as beasts of enormous strength and ferocity, including the following passage from Numbers:

“God brought them out of Egypt; he hath as it were the strength of the unicorn.”

The unicorn also figured into the “Christian Beast Epics” or Bestiaries of the 2nd century AD, the first of which was The Physiologus. A bestiary contained moral tales, in the body of a fable, which began with a quotation from scripture and were followed by “a description of the major traits, real or fancied, of some animal.” The tale ended with a moral lesson. Though repudiated by “Official Christianity,” these tales continued to flourish through Christendom for the next thousand years and, according to Shepard:

“It was chiefly by means of these Bestiaries that the popular as distinguished from the learned tradition of the unicorn was disseminated.”

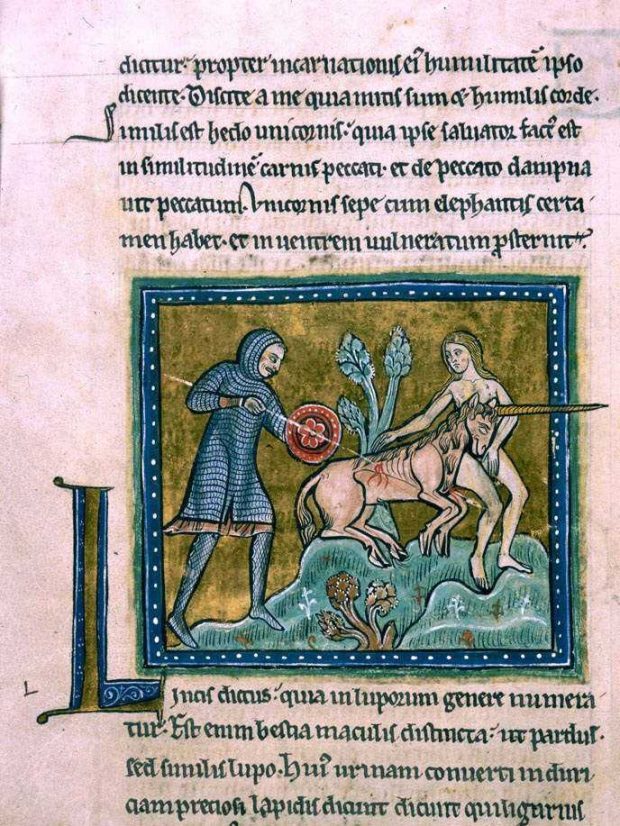

Unicorn Hunt, Rochester Bestiary, 14th century.

Unicorn Hunt, Rochester Bestiary, 14th century.

It is in The Physiologus that we first encounter the description of the unicorn as a small, but fierce beast which no hunter is able to catch without the aid of a virgin. According to the tale:

Men lead a virgin to the place where he [the unicorn] most resorts and leave her there alone. As soon as he sees this virgin he runs and lays his head in her lap. She fondles him and he falls asleep. The hunters then approach and capture him and lead him to the palace of the king.

Some historians interpret this as a symbol of the power of feminine seduction. Others identify the virgin as a symbol of virtue and the unicorn as a symbol of the devil, thus exemplifying the triumph of virtue over evil. And then there are those who imbue the fable with even deeper Christian meaning, viewing the virgin as the Virgin Mary and the unicorn as Christ. Patron saint of Milan, Saint Ambrose, is even quoted as asking:

“Who is this Unicorn but the only begotten Son of God?”

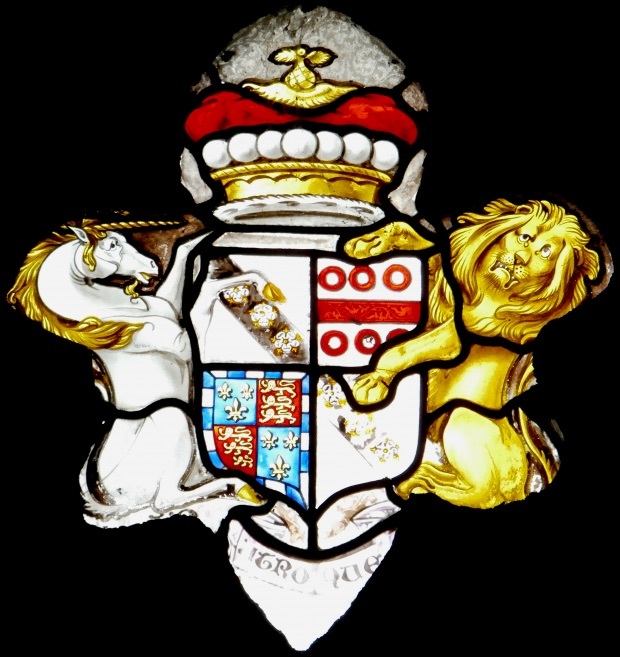

Whatever the deeper symbolism, the image of the virgin and the unicorn is a familiar one. It is the subject of countless paintings and works of art. Indeed, as time passed, no longer was it necessary to read the works of Pliny the Younger or Aristotle in order to learn of the unicorn. Depictions of the unicorn were soon displayed in stained glass, on tapestries, in architecture, and even on coats of arms.

Stained glass heraldic achievement of Lucius Henry Cary, 6th Viscount Falkland. South chancel window, All Saints Church, Clovelly, Devon, 18th century.

Stained glass heraldic achievement of Lucius Henry Cary, 6th Viscount Falkland. South chancel window, All Saints Church, Clovelly, Devon, 18th century.

In Europe, from the 13th century to the 16th century, both ecclesiastical and secular images of the unicorn were widespread, many depictions showing a small, white, horse-like animal with a goat’s beard, cloven hooves, and a spiral horn. In 16th century literature, unicorns are mentioned in several of Shakespeare’s plays as well as in the poetry of Edmund Spenser, who writes in his epic, The Faerie Queene:

“Like a lion, whose imperial power

A proud rebellious unicorn defies.”

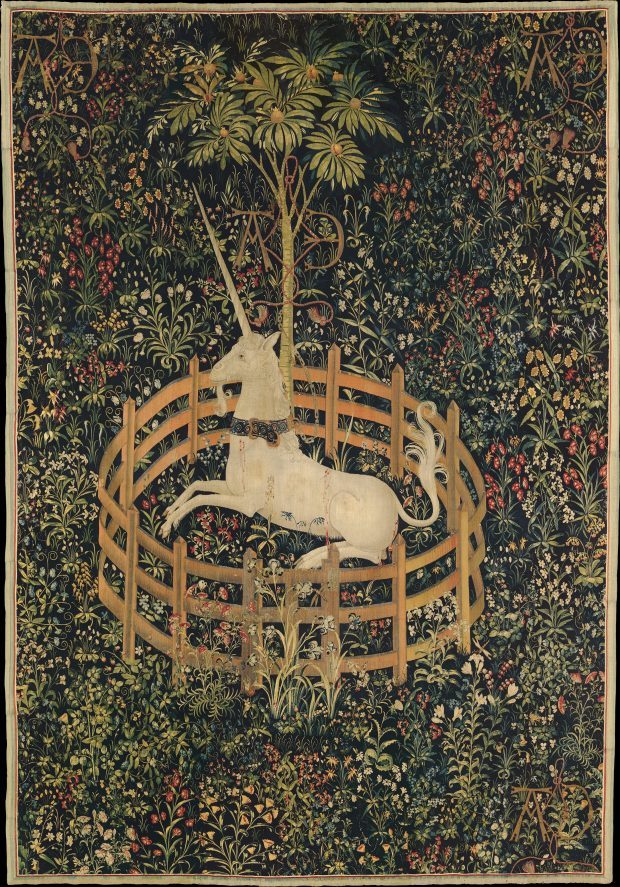

The Unicorn in Captivity. One of the series of seven tapestries The Hunt of the Unicorn, 1495-1505.

The Unicorn in Captivity. One of the series of seven tapestries The Hunt of the Unicorn, 1495-1505.

In his book, The Unicorn Tapestries, author Adolf Cavallo states that by the mid to late 16th century:

“…the unicorn’s existence and its significance as a Christian symbol began to come under theological and scientific scrutiny.”

An Italian scholar of the era even wrote that he believed no one had ever truly seen a unicorn and that a horn on display was actually the tusk of a narwhal. By the early 19th century, a French zoologist went so far as to state that cloven hooved animals had a divided skull and that no horn could possibly grow in the center of it. And, in more recent years, modern scholars have argued that some of the confusion arises merely from inconsistency in translation of primary texts. For example, a word which one scholar translates as “unicorn,” another may translate as “wild ox.”

Today, a unicorn is often represented as a large, white Andalusian horse with a flowing mane and tail and a single, gold spiral horn. As an owner of an Andalusian horse myself, I can certainly support this incarnation of the legend, however it is a far cry from the little, bearded, cloven-hooved creature of antiquity. Was the real unicorn a goat? A wild ass? A rhinoceros? Or did it exist in some magical secret place, revealing itself only to those chosen few who would then come back and tell the tale? Scientists and scholars can certainly hypothesize, but as with many other ancient legends, the truth is we will probably never know.

This article originally appeared on MimiMatthews.com and is reprinted here with permission.

Top photo: The Maiden and the Unicorn by Domenichino, 1602.

More from BUST

This Legendary Dog-Like Monster Is Referenced In “Jane Eyre” And “Harry Potter”

The Original “Beauty And The Beast” Was VERY Different From The Disney Movie

When Mermaid Sightings Were Treated As Fact