Years before Kandinsky and Mondrian, Swedish painter Hilma af Klint created some of the world’s first abstract paintings—then hid them away for decades

History is written—and then it is revised to make space for those who have gone underground, been misrepresented, erased, or otherwise marginalized. The past continuously speaks to the present and to the future through the artifacts it leaves behind.

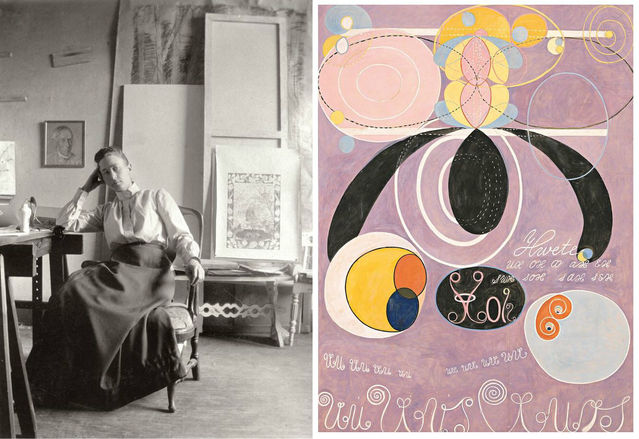

Such is the case with Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint (1862 – 1944), a pioneer in the field of abstraction who kept her work hidden from the public during her lifetime, stipulating in her will that it could not be shared until at least 20 years after her death. Af Klint worked with the understanding that what she was doing was ahead of its time, yet even she might not have been aware of how prescient and necessary her vision would be for the modern era.

The Ten Largest, No. 6, Adulthood, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

The Ten Largest, No. 6, Adulthood, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

One of the first female artists in Sweden to receive a formal art education, af Klint attended the Royal Academy of Fine Arts from 1882 – 87, where she studied classical and naturalist techniques for drawing, as well as landscape and portrait painting. After graduating with honors, she received a scholarship that enabled her to set up a studio in the Atelier Building, which was owned by the Academy of Fine Arts and located in the center of Stockholm’s art district during that period.

Af Klint made a living off the sales of her more conventional work, regularly exhibiting in shows that supported her practice. But at the same time, she maintained a secret life, one that drew from a profoundly spiritual practice that began when her younger sister Hermina died in 1880.

Hilma af Klint in her studio at Hamngatan 5, Stockholm, 1895

Hilma af Klint in her studio at Hamngatan 5, Stockholm, 1895

“On one hand, af Klint was a universally interested woman, very much aware of science, biology, evolutionary theories, mathematics, and geometry,” says Jochen Volz, General Director of the museum Pinacoteca de São Paulo in Brazil and curator of its new show, “Hilma af Klint: Mundos Possíveis” [“Hilma af Klint: Possible Worlds”], on view through July 16. “On the other hand, she was very interested in spiritual knowledge. She was a member of the Theosophical Society in Sweden. She was very Christian, and was very aware of Rosenkreuz’s [mystical medieval Christian] theories. What is amazing is how these different forms of knowledge came together and how she never fell for extremes. For her, they are complementary forms of knowledge.”

These disciplines were honed while she was working as part of a group called “The Five” (de Fem), a secret society of female artists and writers who organized séances to connect with the spiritual realm. They held regular gatherings between 1896 and 1908, meeting on Fridays and following a precise procedure that they carefully recorded in notebooks.

The Ten Largest, No. 7, Adulthood, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

The Ten Largest, No. 7, Adulthood, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

“They would always start with a prayer or song, then read a certain sequence from the New Testament and discuss it,” Volz says. “Then they would get into a state of consciousness where they could communicate with higher spirits, who they called ‘The High Masters (Höga Mästare).’”

It was in this state of consciousness that af Klint’s artistic innovations took place. By 1896, she was creating automatic drawings (where the hand is allowed to move randomly across the paper), a practice that would later be popularized by the Surrealists in the 1920s. “Of course, people in a state of delirium often start to draw and make things, but what this group did was very pragmatically develop a method to get to a form of production through this communication with their High Masters,” Volz notes. “They did it for over 10 years. They were trained mediums and they knew that they could go into this astral plane and come back and make work.”

The Ten Largest, No. 3, Youth, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

The Ten Largest, No. 3, Youth, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

In 1906, at age 44, af Klint got a message from the High Masters stating that she was to create paintings for the “Temple”—though she admitted she never understood what the Temple actually was. Nonetheless, she pushed forward with her Temple work, a leap into pure abstraction that included 193 works—many of them massive, measuring 7.8’ x 10.5’—all structured into subgroups. “The Ten Largest” (1907), her series of paintings depicting the phases of life from childhood to old age, is considered one of the first examples of abstract art in the Western world and predates the first abstract watercolor by Wassily Kandinsky—once considered the father of abstraction.

When the whole Temple series was completed in 1915, af Klint ceased to receive guidance from the High Masters. Yet, she did not abandon her practice nor share the work, even when abstract art and automatic drawing came into vogue.

The Ten Largest, No. 2, Childhood, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

The Ten Largest, No. 2, Childhood, Group IV, 129″ x 94″, 1907

“Af Klint had a very strong sense that what she was doing was ahead of its time,” Volz observes. “She probably was also aware that being a woman doing what she was doing before anyone else would probably cause quite an outrage. It is very likely that she was aware that her practice would not be accepted in her time. We have so many stories in art and cultural history of highly talented, visionary women artists who were in therapy or declared a clinical case. She was aware of the risks she would have been running if she had started to share these works.”

In her notebooks, af Klint reveals that the High Masters instructed her to keep the work a secret, that it was meant for the future, and that the people of her time were not ready for it. Although she struggled with this message, she became convinced, and included in her will that her work was to be kept hidden for at least 20 years after her death. Af Klint died at age 81 in 1944, and in 1970, after her work was finally revealed by her family, it was offered as a gift to the Moderna Museet [the state modern art museum] in Stockholm, but they declined the donation. It wasn’t until 1984 that af Klint’s work was recognized, when art historian Åke Fant presented her pieces at a conference in Helsinki. Today, the Hilma af Klint Foundation holds more than 1,200 works, including 150 notebooks containing some 26,000 pages. “Af Klint systematically studied both spiritual and scientific dimensions, two ways of seeing the world around her,” says Volz of her notes. “She talks a lot about duality. Yellow is the masculine. Blue is the feminine. She uses duality to demonstrate union.”

The Ten Largest, No. 1, Childhood, Group IV, 127″ x 94″, 1907

The Ten Largest, No. 1, Childhood, Group IV, 127″ x 94″, 1907

“That’s the main message she sends us today,” he continues. “We live in a period where everything is radically polarized between good and bad, right and left, religious conflicts, moral standards, et cetera—yet she did not see contradictions but complements. She was convinced that she was painting for the future, and if the future is now, maybe that’s what she has to tell us.”

The Tree of Wisdom, Series W, No. 1, 23″ x 17″, 1913

The Tree of Wisdom, Series W, No. 1, 23″ x 17″, 1913

Story by Miss Rosen

Images courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation, photos by Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2018 print edition of BUST Magazine. Subscribe today!

More from BUST

How Painter Gwen John Started The “Single Women And Cats” Stereotype

Artist Ghada Amer Makes A Feminist Statement With Ceramics and Embroidery

8 Subversive Women Artists To Know