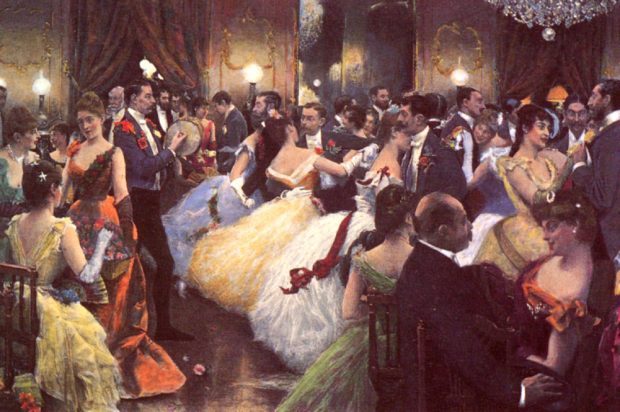

The gas-lit ballrooms of the mid- to late nineteenth century weren’t as flattering to some colors as they were to others. For example, the 1897 edition of Hill’s Manual of Social and Business Forms warns that pale shades of yellow became “muddy in appearance by gaslight,” while shades of rose simply disappeared. Similarly, most shades of purple, as well as darker shades of blues and greens, were known to “lose their brilliance in artificial light.”

As a result, nineteenth century ladies often selected ballgowns and evening dresses in gaslight-friendly colors. Shades of red—like crimson, cardinal, and scarlet—were beautiful by gaslight. Pale blues and pinks could also be quite flattering, as could combinations of bright yellow and white, or pink and white. Additionally, the 1886 edition of Peterson’s Magazine reports that Charles Frederick Worth’s “peachstone-brown” was “a good gas-light color.” While the 1870 edition of Godey’s Lady’s Book describes one color—verd Nile—as “the new gaslight green,” said to be “a favorite hue with blondes.”

British Ball Gown, ca. 1875. (Met Museum)

British Ball Gown, ca. 1875. (Met Museum)

Fabrics adorned with colored gilt or foil accents were another option for gaslight-friendly evening dresses and ballgowns. According to the 1866 edition of Godey’s Lady’s Book:

“Another very attractive style of evening dress is of white tarlatane, powdered with stars or dots of gilt or colored foil—red, green, purple, or blue. The effect is exquisitely light and beautiful, either by day or gaslight.”

Glittery accents were generally quite effective by gaslight. These accents weren’t limited to the fabric or trim on a lady’s evening dress. They could be jeweled hair ornaments, sequined fans, or even diamond-studded flowers. The 1884 edition of Godey’s Lady’s Book reports:

“The last novelty of the season is to wear artificial flowers with diamond centres, simulating dewdrops. This is charmingly effective, more especially by gaslight.”

1830-1840 Diamond Butterfly Hair Pin (Victoria and Albert Museum)

1830-1840 Diamond Butterfly Hair Pin (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Many ladies actually preferred gaslight to daylight—for obvious reasons. In S. Annie Frost’s 1873 short story “Gaslight vs. Daylight,” a lady (Dora) readying for a ball with her friend (Corinne) explains to her young cousin (Daisy) why gaslight must always be preferable for a party:

“To be frank, my dear little innocence, Corinne and I make up rather better for gas than for sunshine. Late hours, balls, operas, concerts, and other entertainments, leave their marks upon the complexion, and the sun is most impudent about exposing such ravages.”

Of course, the story ends as a reflection on authenticity vs. artifice. Daylight-loving Daisy, manages to ensnare Dora’s beau, Oscar. The final lines:

“But,” she said, half-wonderingly, “I thought you loved my Cousin Dora.”

“Not I. Gaslight belles may do to admire, but for a wife, Daisy, give me the pure, fresh face that does not shrink from the daylight.”

London, Pall Mall; and Saint James Street by John Atkinson Grimshaw, c. 1880-1889.

London, Pall Mall; and Saint James Street by John Atkinson Grimshaw, c. 1880-1889.

Choosing a gaslight-friendly ensemble could be a tricky proposition for the nineteenth century lady. Even so, I think many of us would prefer the challenge of gaslight fashion to that of finding shades suitable for 21st century office fluorescents. What do you think?

This article originally appeared on MiMiMatthews.com and is reprinted here with permission.

More from BUST

This Cap Was A Modest Necessity For 19th Century Women

The Rats, Cats, And Mice Of 1860s Ladies’ Hairstyles