In 1922, Ellen Welles Page sat down and penned a letter for the weekly New York magazine Outlook. “If one judges by appearances,” she wrote, “I suppose I am a flapper. I am within the age limit. I wear bobbed hair, the badge of flapperhood. (And oh, what a comfort it is!) I powder my nose. I spend a large amount of time in automobiles. I adore to dance.” But, she went on to explain, there was a reason why folks her age were given to frivolity. “We are the Younger Generation. The war tore away our spiritual foundations and challenged our faith. We are struggling to regain our equilibrium.” Finally, she stated her case: “I want to beg all you parents, and grandparents, and friends, and teachers, and preachers—you who constitute the ‘older generation’—to overlook our shortcomings, at least for the present, and to appreciate our virtues. [Has] it ever occurred to any of you that it required brains to become and remain a successful flapper? Indeed it does! It requires self-knowledge and self-analysis.”

You can’t blame her for feeling a bit defensive. Newspaper headlines declared the flapper “a menace” and “freak of fashion” whose use of cosmetics was “alarming”—yet all across America, girls wanted to be just like her. Whether it was her dark red lipstick, short hair, and skirt cut precariously close to her knees, or her liberal attitudes toward sex, cigarettes, and booze, the flapper represented everything that was mind-blowing and modern about the 1920s. “From the flippant young thing to the more serious-minded young person who eagerly builds herself a career after college, there seems to be a spirit of independence and fearlessness that has nothing whatever to do with a new fashion in hair arrangement,” reported a 1922 New York Times article about the “emancipated army” of flappers.

The term “flapper” originated in the late 1800s in England, where slang dictionaries defined it as both “a fledgling wild duck” and as “a little girl” whose hair flapped against her back while she walked. By the early 1900s, the word had evolved to mean a vivacious, freethinking teenage girl; in 1912, one London theater director told The New York Times, “A flapper is a girl who…is at an awkward age, neither a child nor a woman.” The definition we recognize today took root in the early 1920s, when a pundit griped about “the social butterfly type…the frivolous, scantily clad, jazzing flapper, irresponsible and undisciplined.” Flappers themselves were divided on the word. Called upon to explain her generation to readers of The New York Times in 1922, one young woman said that she and her friends thought of it “as just a magazine word” and never used it. “In fact, the girls I know resent being put in that class,” she added. “And they aren’t prudes either. They are just as eager for a good time and a free life as any set of girls.”

But the flapper was about more than just cocktails and higher hemlines. The 20th century saw women step out of the home and into office jobs vacated by men during World War I. The right to vote was granted in 1920, and around the same time, young women began flocking to colleges in unprecedented numbers. Buoyed by a booming economy, the flapper generation was in a position to take advantage of opportunities their elders never dreamed possible. “Any real girl…who resents being put on a pedestal and worshipped from afar, who wants to get into things herself is a flapper,” read a letter to the editor of The Daily Illini in 1922. Flappers demanded the right to “self-expression, self-determination, and personal satisfaction,” all of which seemed suspiciously self-indulgent and even immoral to generations raised to think of women as the gentle, self-sacrificing protectors of men and family.

The flapper’s look embodied her modern philosophy. Short skirts gave comfort and mobility to girls on the go: a flapper simply refused “to wear uncomfortable clothes because her grandmother considers them ladylike,” explained a reporter in the early ’20s. Instead of granny’s industrial-strength corset, the flapper wore a lightweight one-piece garment known as a “step-in” under a short, straight dress. See-through silk stockings and high heels completed the outfit, along with rouge, powder, and lipstick. Flappers’ use of cosmetics truly shocked the elder generation, who were accustomed to seeing makeup only on actresses and “ladies of the evening.” In fact, an Arkansas coed was expelled from school for wearing it, and a Nebraska college banned cosmetics altogether.

Bobbed hair was another one of the hallmarks of a flapper look, and that fad originated in 1914, when ballroom dancer and fashion icon Irene Castle cut hers before undergoing an appendectomy, to make it easier to care for afterward. The result was known as the “Castle bob,” and it created a sensation. Short hair was just not done before then—after all, long locks were “woman’s crowning glory.” But to women used to hot, heavy tresses and fussy pompadour styles, bob cuts offered what Good Housekeeping called “freedom and simplicity.” Short hair immediately marked a woman as having modern, perhaps dangerous, ideas. School superintendents of eight towns in upstate New York barred teachers with bobs in 1922, reasoning that they were “faddists” incapable of teaching “common sense and judgment.”

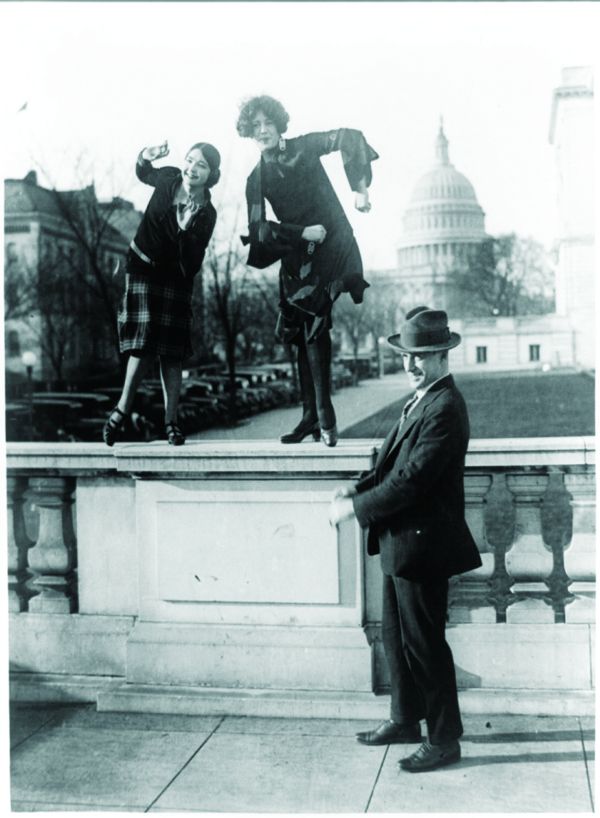

But images of flappers were everywhere. Colleen Moore made a silent-film career out of portraying sassy, good-hearted flappers, while Clara Bow portrayed flappers whose sexuality threatened to destroy men. If a young woman wanted to dress like one of these actresses, she only had to open the latest Sears catalog, which brought cutting-edge fashion to the masses outside major cities. And while walking down the street in flapper fashion was daring, it helpfully identified a flapper to other members of her tribe.

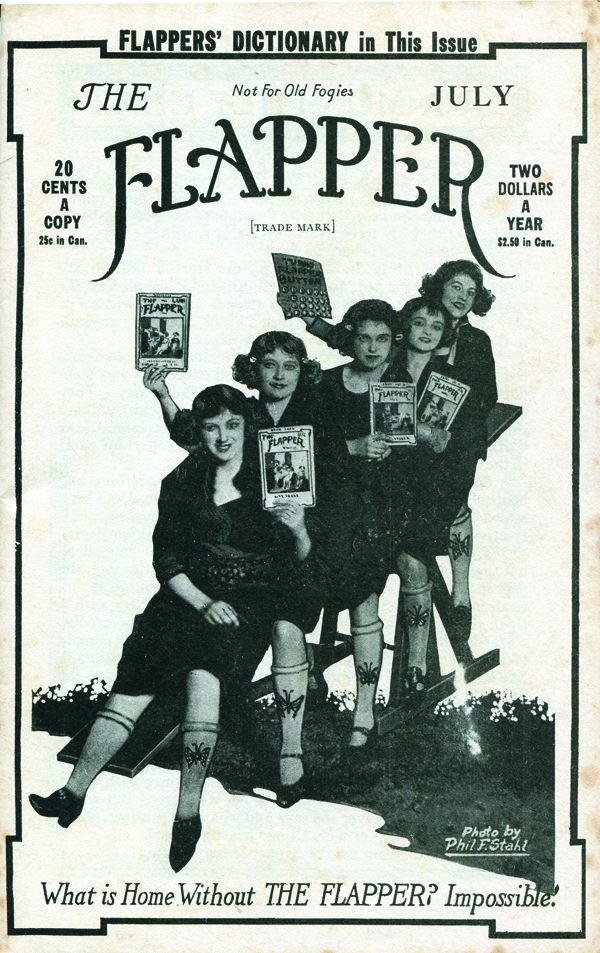

A magazine called The Flapper (tagline: “Not for Old Fogies”) catered to this new woman. It celebrated her and cheered the “doom…of the timid, trusting, retiring, servile, opinionless, unattractive, shrinking creature known as the old-fashioned girl.” As one 19-year-old explained in its pages, “I am for rolled stockings, short skirts, knick[er]s and everything such, but down with the old-fashioned ideas.” The Flapper challenged traditional gender roles, publishing photos of its readers and their boyfriends cross-dressing and asking rhetorically “whether all the blame for extremes in behavior deserves to be centered on the flapper, or whether it can be traced to the male of the species to whose whims she is supposed to constantly cater.” The magazine also reflected its readers’ burgeoning interest in organized feminism; the November 1922 issue included a picture of a 15-year-old flapper at the National Women’s Party convention in Connecticut. The purpose of the party was to “have passed in every state a blanket law which will do away with sex discrimination and make all citizens of the U.S. equal in the course of justice” (an early reference to the ill-fated Equal Rights Amendment).

Though clearly flappers had more on their minds than partying, many parents still aggressively frowned upon flapper behavior by their daughters, with sometimes-disastrous results. “My daughter wants to be a flapper” was the reason a Chicago man gave to a judge for why he broke his 16-year-old’s nose when he caught her plucking her eyebrows; he was fined $5 for disorderly conduct, a pittance even by 1922 standards. The following summer, a 14-year-old would-be flapper committed suicide when her parents refused to let her bob her hair and wear the latest fashions.

Short skirts and silk stockings were bad enough, but flappers also smoked and drank, habits that had previously been men’s territory. A number of towns and cities had even tried to ban women from smoking in public, on moral grounds. When a New York alderman instituted a similar ordinance, female smokers raised such a ruckus that it was rescinded the very next day. The staid Ladies Home Journal excoriated “Women Cigarette Fiends”; meanwhile, around the country, college women fought to have smoking lounges installed in their dormitories. From 1923 to 1929, the number of cigarettes consumed by women doubled. And while booze was illegal during the Prohibition years of the 1920s, as a former flapper remembered, “what is forbidden is fun, and we chose to drink.” The flapper’s rum-filled hip flask was “a national menace to girlhood,” according to the superintendent of New York’s Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Perhaps most disturbing to a disapproving society were flappers’ newfangled sexual mores, as exemplified in the practice known as “petting.” Automobiles helped initiate a sea change in dating and attitudes toward sex, moving dating away from parents’ watchful eyes and into an unchaperoned back seat, where anything could happen. Petting ran the gamut from casual kissing to “more intimate caresses and physical fondling,” and “petting parties” made for especially tantalizing headlines. Five girls (including a 14-year-old) and three boys were expelled from a Hammond, Indiana, high school after an investigation by the principal revealed frequent trips to a local lovers’ lane and “petting parties lasting into the early hours of the morning.”

Flappers also developed their own slanguage, which instantly divided “flaming youth” from their fuddy-duddy parents (creating a generation gap that rivaled that of the 1960s). By 1925, it was “positively unfashionable” for hip young people to “speak straight American,” declared the UCLA student newspaper. A flapper who got married was said to be “buried,” and flappers went on dates with “jellybeans,” “sheiks” (after the Rudolph Valentino film of the same name), or “cake-eaters.” The latter was a dandy who spent his money on clothing and therefore subsisted on “cake furnished at ‘social functions’ by his girl friends.” “Father Time” was any man over 30 years of age; his female counterpart was considered a “Rock of Ages.” A boy or girl who refused to pet was a “holaholy” and considered no fun at all.

Older generations predictably clutched their pearls and proclaimed the end of the world as they knew it—sometimes literally. An evangelist known as the Texas Tornado told The New York Times, “Girls think more of their eye lashes and ‘nude’ hosiery than they do of decency. Home life is broken up; respectful law goes with it; wholesale iniquity follows; then—war.” A college president fretted, “What can we do when the daughters of the so-called ‘best people’ come out attired scantily in clothing but abundantly in paint, with a bottle of liquor not on the hip but in the handbag, dance as voluptuously as possible…[and] engage in violent petting parties in the luxurious retreat of a big limousine.” In a 1922 essay, 41-year-old journalist Kathleen Norris said that women of her generation looked “with honest pity and contempt at the painted lips and the uncorseted, half-clothed little figures” of the flappers who some day would “want to be sweet and dignified women” but wouldn’t know how.

A flapper who stuck up for her generation made the wire services around the time Norris’ essay appeared. Margaret Persell, a 17-year-old Chicago girl, anointed herself and four of her friends “The Royal Order of Flappers.” Their slogan was “Down with Reformers.” They told reporters, “A lot of old men and women who haven’t any flapper daughters” were trying to dictate their behavior, and they were “sick of it.” In an action designed to grab attention, Persell and her second-in-command burst into Chicago’s city hall on April 17, 1922. Their ultimately unsuccessful plan was to see the mayor and seek his “protection” from the “unpleasant publicity” that resulted when local preachers criticized the flapper lifestyle.

As the decade ended, the flapper “menace” faded, and skirt hems lowered. With the stock market crash in October 1929 and the coming of the Great Depression, flappers redirected their energies away from revolution and rowdy behavior. The rise of fascism and war clouds on the horizon also didn’t make for frivolous times, and the sight of bobbed hair or short skirts had lost much of its capacity to shock. But the flappers’ love of freedom and fun was handed down to generations of girls after them, and their modernized image of womanhood remains to this day. A poem published in The Flapper in 1922 described “The New Fashioned Girl”—a girl whose legacy was firmly imprinted on society: Let them shed all their tears in a crocodile pour / For the simple simp sister who flourished of yore / But I’ll cast my vote in the way that I feel— / For the girl self-reliant, bright, snappy and REAL.

Flapper Slang Dictionary

(from tge July 1922 issue of The Flapper)

Alarm Clock—Chaperone

Apple Sauce—Flattery; bunk

Barneymugging—Lovemaking

Berries—Great

Blow—Wild party

Cat’s Particulars—The acme of perfection; anything that’s good

Clothesline—One who tells neighborhood secrets

Dapper—A flapper’s father

Dumbdora—Stupid girl

Duck’s Quack—The best thing ever

Eye Opener—A marriage

Feathers—Light conversation

Fire Extinguisher—A chaperone

Flour Lover—Girl who powders too freely

Frog’s Eyebrows—Nice, fine

Gimlet—A chronic bore

Grummy—In the dumps or blue

Handcuff—Engagement ring

Hen Coop—A beauty parlor

Hush Money—Allowance from father

Johnnie Walker—Guy who never hires a cab

Let’s blouse—Let’s go

Meringue—Personality

Munitions—Face powder and rouge

Noodle Juice—Tea

Out on Parole—A person who has been divorced

Petting Pantry—Movie

Seetie—Anybody a flapper hates

Smoke Eater—A girl cigarette user

Tomato—A young woman shy of brains

Umbrella—young man any girl can borrow for the evening

Wurp—Killjoy or drawback

—–

by Lynn Peril

First Photo: Actor Dorothy Sebastian, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Bain News Service

Other Photos: The Flapper cover, Lynn Peril; Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Photo Co. (dancing)

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2013 issue of BUST. Subscribe!

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2013 issue of BUST. Subscribe!