By 1586 Mary, Queen of Scots had been imprisoned by her cousin, Elizabeth I, for almost two decades.

She’d lost her throne in 1657, having been forced to abdicate in favor of her baby. Then, after fleeing Scotland for safety in England, she’d been (at least in her mind) royally screwed over. Instead of helping Mary regain the Scottish throne, Elizabeth had her locked up.

Mary was a serious threat to Elizabeth’s rule. Viewed by Catholics as the true Catholic ruler of England, there was many a plot to bump off Elizabeth and put Mary on the throne.

Thus, Mary was imprisoned, spending year after year dragged around England, locked up in its various castles.

So you can see why, approaching her 20th year of imprisonment, Mary eagerly took part in a plot to assassinate Elizabeth.

Enter: The Babington Plot. Put together by young nobleman Anthony Babington and priest John Ballard, along with other conspirators, the plot was an incredibly convoluted scheme to:

While, locked away, Mary advised the plotters, both in terms of strategy and how to ensure she’d win the English throne. And naturally, as the “rightful” ruler of England, Mary would be the one to sign off on the plot starting. Which she did, in July 1586.

Unfortunately for Mary, the plot had been infiltrated and Elizabeth I’s own spy master, Sir Francis Walsingham, had been using the letters to entrap Mary and get her to call for Elizabeth’s murder—which, by signing off for the plot to go ahead, she’d done.

Everyone involved with The Babington Plot, including Mary, was duly arrested.

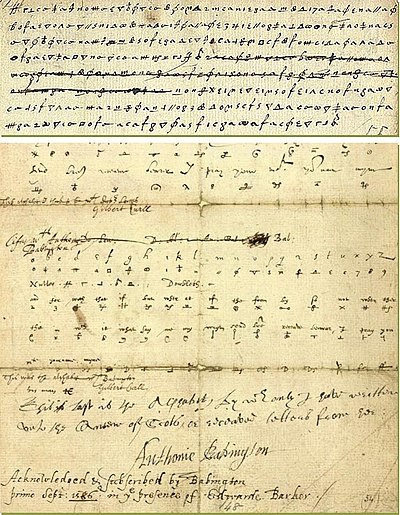

The Babington Plot postscript and its secret cypher

The Babington Plot postscript and its secret cypher

In September 1586 the first of the conspirators were executed, including ringleaders John Ballard and Anthony Babington. Onlookers said that by the time Ballard arrived at the execution site, his limbs were barely in their sockets as a result of the torture he’d undergone.

One at a time, the men were hung, drawn, and quartered, forced to watch their fellows’ dismemberment before their own death. The executions were so brutal that a public outcry meant the other conspirators were just “hung until they were quite dead” before being dismembered.

With that bloodbath over, the attention turned to Mary. What could be done with the traitorous Queen?

The idea of executing a Queen was very possible. After all, Elizabeth’s own mother, Anne Boleyn, had been beheaded. But this wasn’t a outcome that Mary entertained.

In her mind, she had been anointed by God to reign. That was something holy and untouchable. There was no law in the land that could hold jurisdiction over her; the only judgement she was accountable to was God’s.

However, it quickly became apparent that it wasn’t God’s holy anointed Mary going on trial for treason, but (as the royal warrant for the trial put it) Mary, a mere woman who was:

“Pretending title to this crown of this realm of England.”

Mary’s trial hearing started on October 14, 1586, though it operated as less of a trial and more of a really long argument between Mary and those convicting her.

To say Mary would have made an excellent lawyer would be an understatement. She rallied hard, with a stream of well thought-out and articulated arguments, always ready with something to fight the prosecutions, threats, and refusals to acknowledge her words.

Mary’s arguments included:

After Mary’s hearing was finished, the trial was adjourned to The Star Chamber, leaving Mary at Forgeringay Castle. Then on October 25, the trial was completed…without anyone telling Mary.

The trial’s commissioners found Mary guilty of treason. And together with Parliament, they urged Elizabeth to execute Mary as quickly as humanly possible.

BUT Elizabeth didn’t want to execute Mary.

Though there’d been a lot of bad blood between the pair of Queens, there had also been a kind of respect. They were so similar in so many ways, cousins thrust into positions of power, considered above their gender. No matter how begrudging, there was a bond there.

After Mary’s second husband, Lord Darnley, died in an incredibly suspicious explosion, Elizabeth wrote to Mary, urging her to distance herself from the scandalous tragedy, as:

‘I treat you as my daughter, and assure you that if I had one, I could wish for her nothing better than I desire for you.”

But even more important than the bond Elizabeth shared with Mary, she didn’t want to execute her because it set a deadly precedent: to lawfully kill a sovereign.

Elizabeth had hoped she’d be able to pardon her cousin, that Mary would beg for forgiveness. But none of that happened.

As pressure mounted from her councillors and parliament, Elizabeth had no choices left. On February 1, 1587, she signed Mary’s death warrant. With the warrant signed, Elizabeth’s councillors decided to carry out the execution immediately – without telling Elizabeth.

On the evening of February 7, Mary was visited at her prison of Fotheringhay Castle and told she was to die the next morning.

Her last hours were spent both in prayer and sorting out her affairs. Sleeping would be near impossible, thanks to the incessant loud hammering as the execution scaffold was hastily erected.

Early on the morning of February 8, Mary serenely entered the castle’s great hall to face the scaffold. And after that, everything turned into a shit show.

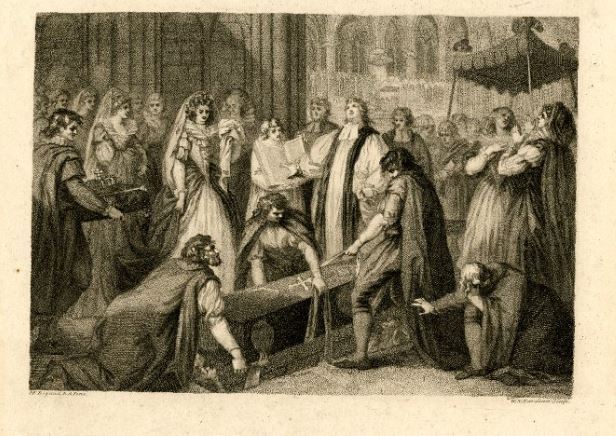

Mary bids her servants farewell in a 19th century re-imagining (which explains the sheer drama here)

Mary bids her servants farewell in a 19th century re-imagining (which explains the sheer drama here)

To kick things off, Mary was curtly informed that she was to go to her death alone. This was a shock. Traditionally, women of Mary’s status were allowed their ladies around them on the scaffold. They not only gave one last herald of the condemned’s status. But, perhaps more importantly, the women provided comfort before the axe fell and then shielded the broken body, offering dignity in death by not subjecting the woman to being stripped by men for burial.

To be rejected this right at the last minute was a huge blow.

Though she maintained a calm exterior, Mary begged to be allowed her ladies. She was rejected, but refused to give up, pleading for this, her final right.

Eventually, the councillors gave in on condition that Mary’s ladies didn’t loudly weep, wail, or generally erupt into female hysteria.

And so Mary climbed the stairs of the scaffold, her ladies in tow.

As Mary waited for the death sentence to be read out, a man burst forth from the crowd. Dr. Fletcher, The Protestant Dean of Peterborough, proclaimed that it wasn’t too late for Mary to save her soul and convert from Catholicism to the Protestant faith.

Mary ignored his loud protestations and prayers, until eventually breaking and saying:

‘Mr. Dean, trouble not yourself any more, for I am settled and resolved in this my religion, and am purposed therein to die.’

In response, the Dean fell to his knees on the scaffold’s stairs and started loudly praying at her. Mary politely turned away and began her own prayers.

Despite the Dean’s complete inability to read a room, Mary finished her prayers. With this over she stood, readying herself for this final act of ceremony.

She paid the executioner, forgiving him in advance for what he was about to do. Then, Mary’s ladies helped her remove her black gown, revealing a red petticoat with deep crimson sleeves.

This color wasn’t a a random choice, but the red of Catholic martyrdom. Mary was making a clear statement – she was anointed by God, to kill her was a sin, and in death, she would become a holy martyr.

The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. Artist unknown.

The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. Artist unknown.

The wordless statement from Mary’s blood red petticoat rang throughout the great hall, even as Mary was blindfolded, head laid on the block, and arms stretched wide to signal the executioner’s axe.

The first blow hit the back of her head.

Accounts vary on if Mary cried out from the pain or remained silent. However, as this was a chop wound (a mix of sharp force and blunt force trauma) it’s most likely that Mary felt excruciating pain for a few seconds before losing consciousness.

The axe’s second blow hit her neck, severing it almost entirely, with one third chop needed to separate Mary’s head from her body.

The executioner then picked Mary’s head up by the hair, held it forth to the crowd and proclaimed,

‘God save the Queen’

At which point, he lost grip on the head as Mary’s wig fell off, revealing her greying hair (something people were shocked about, despite the fact she was 44 and they’d just witnessed her bloody execution).

And with that macabre farce, the story of Mary Queen of Scots came to an end.

This article originally appeared on F Yeah History and is reprinted here with permission.

More from BUST

You Decide—Lost Russian Princess, or History’s Greatest Scammer?

The Real Story Behind “The Favourite”

Lucilla: The Ex-Empress Who Tried To Murder Her Brother